New Alum Earns Top Author Honors for Vassar Undergrad Research on Spiders

It’s always noteworthy when a Vassar student is awarded authorship on a paper in a scientific journal for research conducted with members of the faculty. This spring, Max VanDyck ’23 achieved the rare honor of being designated as First Author of a paper that sheds new light on how certain species of spiders have become adept at catching moths in their webs.

In the paper, published on April 23 in the journal Biomimetics, VanDyck and his co-authors, including Vassar Biology Professor John Long and Candido Diaz ’11, soon to be Assistant Professor of Biology at Stetson University, broke new ground in determining the chemical makeup of the glue that enables the spiders to trap the otherwise elusive moths. The team is funded by the National Science Foundation. Moths are able to escape most spider webs by shedding a powdery layer of scales on their wings, Long explained, but a few species of spiders produce a glue with a lower viscosity that seeps under the powdery substance before the moths can escape, and the glue hardens almost instantaneously, trapping the moths onto the webs.

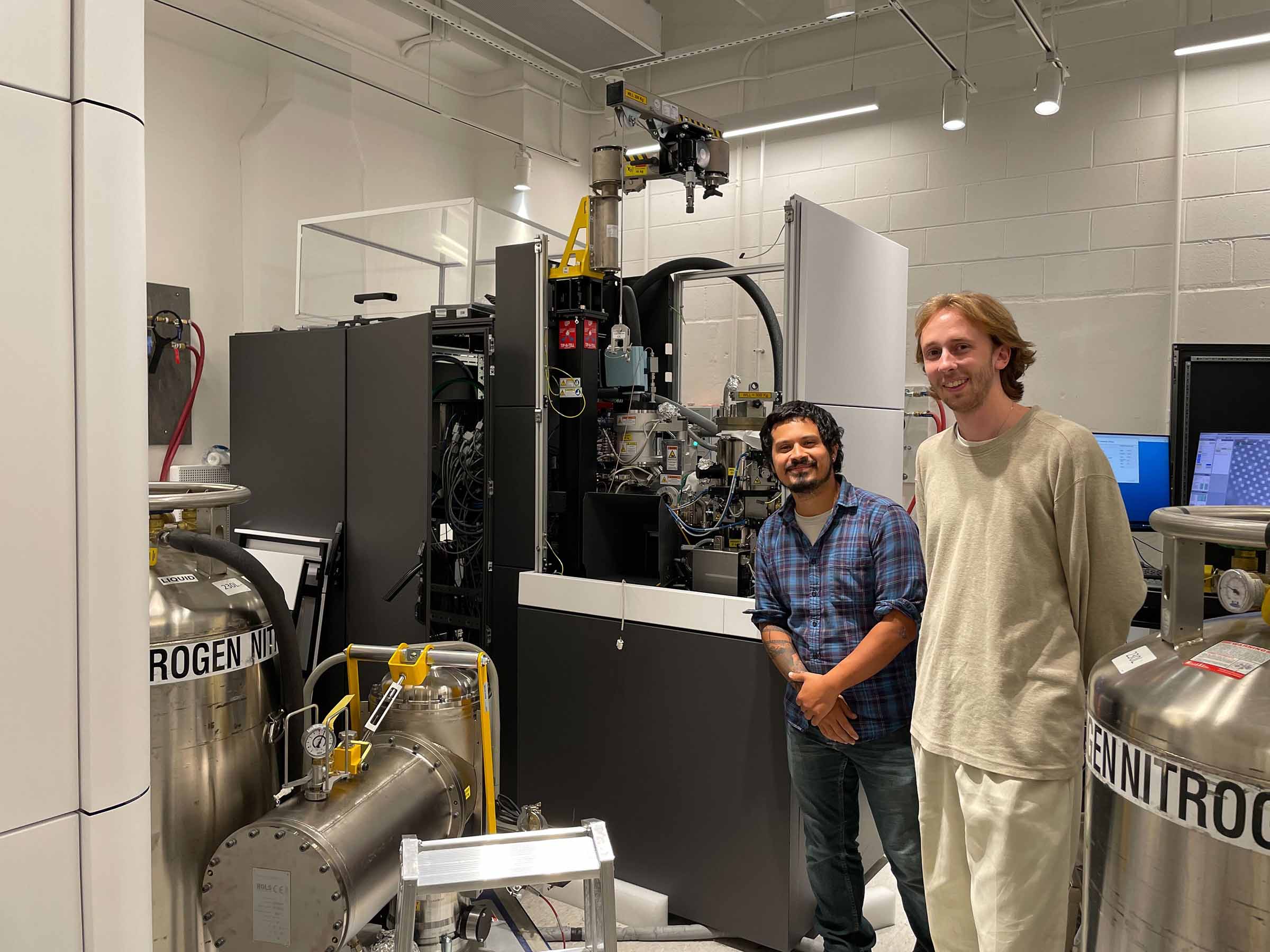

Long said VanDyck was awarded top authorship because it was principally his research that unlocked some of the secrets to the spiders’ success, and he was integrally involved in writing the initial and final drafts of the paper. During research for his senior thesis, VanDyck used Vassar’s Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectrometer to analyze the chemical makeup of various spider glues, Long explained. “Max’s senior thesis served as the first draft of our paper,” he said. “He had the knowledge that enabled him to analyze the glue components in the NMR, and he had the storytelling ability to make the findings known in Biomimetics.” Other co-authors of the paper were Richard Baker and Cheryl Hayashi, scientists at the American Museum of Natural History.

VanDyck, who is currently working in a research laboratory in the Department of Biological Chemistry and Molecular Pharmacology at Harvard Medical School, credited Long and Diaz with providing the training that enabled him to make major contributions in writing the paper. “My goal was to find out how the glue droplets from these spiders were able to catch moths,” he said. “I was the biochemist of the team.”

VanDyck said analysis of the spider glue droplets by others in the field have indicated that they are composed of water, some proteins, and salts. Since water does not change and spider glue proteins are thought to be conserved, he and his co-researchers concluded that the makeup of the salts must be key to explaining how these spiders are able to manufacture this moth-catching glue. Diaz, who has been collecting spiders from several continents and analyzing their glue for several years, said VanDyck brought his knowledge of biochemistry to the project. “Max was enthusiastic and hardworking right from the start of our research,” he said, “and all of his efforts paid off with this paper. It was really great working with him.”

VanDyck, who plans to apply to medical school next year, said he is certain that being awarded first authorship in a prestigious scientific journal will help advance his career, and he credits Vassar for making it happen. “This kind of research at the undergraduate level is made possible at a place like Vassar where students are working closely with faculty,” he said.

Long said Vassar has created a culture in its science departments that lends itself to this kind of success. “We have a history of independent study that involves our undergrads,” he said. “We are able to demonstrate what it takes to be a professional scientist.”