Essay

Vincent and Vassar

By Colton Johnson

Vassar College Historian

A few months after Edna St. Vincent Millay died she was the subject of “Vincent at Vassar,” an essay in Vassar Quarterly by her Vassar mentor and longtime friend, Professor of Latin Elizabeth Hazelton Haight, a member of the Class of 1894. “Once I taught a genius,” Miss Haight wrote, “and she became my friend. It all began when I was told that ‘a poor young poetess’ from Camden, Maine, was coming to Vassar, but could not pass our stiff entrance examination in Latin writing. I offered to tutor her by correspondence.” The unconventional start of what became an enduring friendship prefigured the peculiar relationship between Millay and her alma mater.

The young poetess had been 12 in 1904 when her parents, long separated, were divorced, leaving the support of the family to her mother, a traveling nurse. Herself an occasional writer of children’s stories and nature sonnets, Cora Millay used poems to teach her eldest daughter to read at the age of five. A subscriber to Harper’s Young People when she was nine, Vincent, as she was called, had already begun to craft exploratory verses. She and her younger sisters, Norma and Kathleen, were also devoted readers of Scribner’s St. Nicholas Magazine, a children’s monthly that annually offered badges and a cash prize for work submitted by young writers under 18. “Forest Trees” by “E. Vincent Millay” appeared in the magazine in the summer of 1906, the first of eight of her poems to appear there over the next four years. Two years later 16 year-old Vincent gathered her poems into a notebook, “The Poetical Works of Vincent Millay,” which she dedicated to her mother, “whose interest and understanding have been the life of many of these works and the inspiration of many more.” By the end of 1910 the poetical works numbered 61.

The first poem in the collection, “The Land of Romance,” had won the St. Nicholas Gold Badge in 1907 and was reprinted in the prestigious journal Current Literature, with a note by its editor, Edward J. Wheeler, a founder of the Poetry Society of America: “The poem…seems to us to be phenomenal…. Its author (whether boy or girl we do not know) is but fourteen years of age.” Norma Millay recalled the award as confirmation within the family that “Vincent was a genius.”

In 1910 Vincent received the St. Nicholas cash prize and was designated an Honor Member for the “clever rhyming” and “ingenious setting” of her double-rhymed final submission, “Friends,” in the May-October issue. Responding, as “Edna Vincent Millay,” she told the magazine’s editor, “I am writing to thank you for my cash prize and to say good-by…. I am going to buy with my five dollars a beautiful copy of Browning, whom I admire so much that my prize will give me more pleasure in that form than in any other.”

—————

Two events in 1912 brought poetry and Vassar College together for Vincent. In March, while she was away from home aiding her ailing father, her mother sent her an announcement of the debut of The Lyric Year, a projected annual publication that aspired, as its unidentified editor explained, “to the position of an Annual Exhibition or Salon of American poetry, for it presents a selection from one year’s work of a hundred American poets.” Poets were invited to send as many examples of their work as they wished to the volume’s publisher, the New York editor and publisher Mitchell Kennerley. Three cash prizes totaling one thousand dollars were to be awarded for the first, second and third best poems, as determined by three judges: the Boston poet, editor and anthologist William Stanley Braithwaite; Edward J. Wheeler; and “The Editor.” “Here is your chance,” Vincent’s mother had written on the top of her letter, “Think what Wheeler said of your Land of Romance.” By May Vincent had finished a long poem begun in 1911, and, along with at least four other poems, “E. Vincent Millay” submitted “Renaissance” to Mitchell Kennerley.

InSavage Beauty, her definitive biography of Millay, Nancy Milford skillfully traces the ensuing correspondence between Vincent and the editor of The Lyric Year, the eccentric painter, poet—and, later, film producer—Ferdinand P. Earle. His coy teasing about his identity matched hers about her actual name and gender, and the extended communication between the two was marked with taunt and innuendo. As the summer went along he suggested certain changes to “Renaissance,” at least two of which Vincent accepted, and more than once he implied that she had the best chance to win the competition’s first prize. While he apparently didn’t mention it to Vincent, Earle was eagerly informing poetic colleagues like the Iowan member of the Davenport Group, Arthur Davison Ficke, about the astonishing new, perhaps female, poet named Vincent. Ficke in turn was discussing the work of the new poet (or poetess) with his friend from Harvard days, the New York poet Witter Bynner. Writing as “The Editor” to “Dear Sir” on July 17, 1912, Earle told Vincent that “Renascence” (the subtly more topical title was one of his suggestions) had been accepted for The Lyric Year. Reiterating his high enthusiasm for the poem, Earle asked for a biographical sketch. Thinking by now that “The Editor” must be the volume’s publisher (or his wife), Vincent sent a brief, impish biographical note to the no doubt dumbfounded Mitchell Kennerley in New York.

Revealing that she was “just an aspiring Miss of twenty” and giving her full name, she expressed her temerity about being edited and judged by the likes of Kennerley and Braithwaite. She expressed, however, some comfort that— whoever “The Editor” was—her admirer Edward Wheeler was also to have a voice in the judging. “It was the fact,” she said, “that he had once been pleased with my work which gave me courage to enter the competition.” “If I were a noted author,” she continued, “you would perhaps be interested to know that I have red hair, am five feet-four inches in height, and weigh just one hundred pounds; that I can climb fences in snowshoes, am a good walker, and make excellent rarebits. And if I were a noted author I should not hesitate to tell you…that I play the piano—Grieg with more expression than is aesthetic, Bach with more enjoyment than is consistent, and rag-time with more frequency than is desired.”

Ten thousand poems from nearly 2000 writers of verse were submitted to The Lyric Year, and among the 100 poems chosen for the volume were works by such eminent poets as William Rose Benét, Witter Bynner, Bliss Carman, Arthur Davison Ficke, Joyce Kilmer, Richard Le Gallienne, Vachel Lindsay, Sara Teasdale, Louis Untermeyer and John Hall Wheelock. Earle’s biographical note about Millay obliquely cited his fellow judge, Edward Wheeler: “Edna St. Vincent Millay was born in 1892. At the age of fourteen she revealed, to quote an eminent critic, ‘phenomenal’ promise as a writer of verse; and has carried off no little honor during her brief career.” Despite Earle’s own choice of “Renascence” for the First Award, Vincent was not among the top three poets in the competition, coming in at fourth place, just short of the cash awards.

This outcome disappointed and frustrated Vincent, but when advance copies of The Lyric Year reached its contributors, several reactions to “Renascence” provided fresh encouragement. Visiting Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Ficke in Davenport for Thanksgiving in 1912, Witter Bynner had read the poem aloud to Ficke as they sat at the foot of the Soldier’s Monument, prompting a letter to Vincent from Ficke, Mrs. Ficke and Bynner, saying, “This is Thanksgiving Day, and we thank you.” Vincent’s reply two days later opened long and convoluted friendships: “You are three dear people. This is Thanksgiving Day, too, and I thank you. Edna St. Vincent Millay.”

By New Year’s Day “Renascence” had been praised at length in the New York Times by its poetry reviewer, Jessie Rittenhouse, as “the freshest, most distinctive note in the book,” and in The Chicago Post by the poet and critic Louis Untermeyer. “From a conventional standpoint,” Rittenhouse conceded, “‘Renascence’ is frequently crude,” but in conclusion she asked, “who will fail to recognize the freshness, the originality of it all?” Untermeyer offered the poem similar kudos, declaring it “the surprise of the volume.” Rittenhouse, a co-founder in 1910 of the Poetry Society of America and its secretary, asked Vincent to come to New York and read at a meeting of the society. Thanking Arthur Ficke on January 13, 1913, for sending Untermeyer’s review, Vincent revealed that she “had already a copy from Mr. Untermeyer, with whom I am also corresponding.”

—————

Vincent’s second decisive event in 1912 began with her improvised performance at a masquerade dance and staff party in August at the Whitehall Inn, a summer hotel in Camden. Her sister Norma, who had a job there that summer as a waitress, convinced the reluctant Vincent to come along to the dance. Wearing “a little Pierrette costume,” Norma told Nancy Milford, and “a tiny black velvet mask with rosettes of red crepe paper…with her long red-blond hair she looked about fifteen.” Vincent won the evening’s prize for best costume and Norma the prize for best dancer. There was ice cream afterward in the music room, Norma recalled, and Vincent “played the piano and sang, jazzy and bright and quick…. Finally after she’d sung her songs, I said, ‘Ask her to recite “Renascence.”’ She turned on the piano stool and said the poem. Then it was absolutely still in that room.”

One of the auditors of Vincent’s impromptu was a guest at the inn, Caroline B. Dow. A member of Vassar’s Class of 1880, Miss Dow was the founding dean of the Training School for Secretaries of the Young Women’s Christian Association in New York City. When, by popular demand, Vincent performed again at the inn—playing the piano and reciting again her 214-line poem—Miss Dow’s questions about her plans for the future led to a discussion with Cora Millay. “Miss Dow wanted to come up and talk to Mother, privately,” Norma recalled. “Of course, Vincent had to go to college.” Dow declared it unthinkable that the author of “Renascence” not attend college, and she disclosed a plan by which she and some of her wealthy acquaintances might support Vincent’s studying at Vassar.

In October Vincent sent Miss Dow, at her request, a list of her high school courses, an assessment of her literary proficiency—in three categories: “Authors with whom I am very well acquainted;” “Well acquainted with;” “Slightly acquainted with”—and a list of some two dozen authors and their works, labeled “Have read.” As to her high school record: “the only other courses provided that might be of use to me I think are Physics and Solid Geometry. I could take them up next term, if you think best.”

Another member of the audience at the Whitehall Inn had brought Vincent to the attention of her own alma mater, Smith College. At her encouragement, Charlotte Bannon, another Smith graduate who lived in Northampton, Massachusetts, began a kindhearted and encouraging correspondence with Vincent which culminated in an offer of a full scholarship at Smith for the following academic year from President Marion Burton. Writing on January 6, 1913, to her mother, who was traveling, Vincent said she was having “lots of fun looking up names” in the catalogues of the two colleges. “In Vassar now,” she wrote, “there are four girls from Persia, two from Japan, one from India, one from Berlin, Germany, and one or two others from ‘across the water.’” Naming the Japanese students, she asked, “wouldn’t it be great to know them? There isn’t one ‘furriner’ in Smith. Lots of Maine girls go to Smith; very few to Vassar. I’d rather go to Vassar.” In closing, she echoed a peculiar statement by Carl Sandburg on his idealism: “I don’t know where I’m going but I’m on my way.”

—————

A week later Vincent received a telegram from Miss Dow, telling her to come at once to New York City. Entry requirements at Vassar posed more difficulty than acceptance at Smith. The arbiter of what was needed for Vincent’s admission to Vassar was the college’s new dean, Ella McCaleb ’78, who had suggested to Miss Dow that a semester’s study at Barnard College as a non-matriculated student might supply Vincent with most of the needed course-work. With her appointment in 1913 as Vassar’s first dean, Miss McCaleb, formerly the secretary of the college, added disciplinary authority to her previous responsibilities, among which had been review of admission applications, conduct of most of the college’s correspondence and maintenance of students’ academic records.

Vincent’s study of English, French and Latin at Barnard began on the first of February and ran until the end of June.

Her letters to her family, Arthur Ficke and others say less about her studies than about the excitements of New York City, particularly her reception by literary New York: “a note from Sara Teasdale, inviting me to take tea;” “the luncheon given by the Poetry Society to Alfred Noyes;” “My party at Miss Rittenhouse’s. She told them they were there to meet me.… Mr. and Mrs. Edwin Markham.…Sara Teasdale, Anna Branch, Edith M. Thomas (tell Mother to hunt her up in thoseAtlantic Monthlys);” “Yes, I have seen and talked with Witter Brynner.…Later, he read Renascence aloud;” “read me in the July Forum;” “I’ve had a wonderful time with the Kennerleys this spring;” “Mr. Kennerley wants me to let him publish a volume of my stuff.” As spring came on Vincent spent a good deal of weekend time with Mitchell Kennerley and his wife at their home in Mamaroneck, in Westchester County, where she met Arthur Hooley, the charming British editor of the American literary journal, The Forum, of which Kennerley was publisher.

During Vincent’s time at Barnard, Caroline Dow introduced her to Frank L. Babbott, a wealthy collector and philanthropist, and his daughter Lydia Pratt Babbott, “two of the Vassar people,” Vincent had reported to Cora, in unwitting understatement. Lydia was to matriculate at the college in the fall, her father would be a trustee in two years, and her mother, Lydia Richardson Pratt, the daughter of Vassar trustee and benefactor Charles Pratt, had been Miss Dow’s roommate when she attended Vassar in the Class of 1880. “I made a decided impression on them both,” Vincent said, “but especially on Mr. Babbott, who just simply fell in love with me.”

Vincent’s work at Barnard was successful, but it lacked the needed work in Latin prose and in algebra. Writing to Vincent’s Barnard dean on June 27, Dean McCaleb reviewed Vincent’s summer studies and disclosed her own dilemma: “She is surely an interesting and promising young woman, but just what she should do next year is an open question and one upon which I am seeking light.” In early July Vincent sent a vexed request to Dean McCaleb for assistance. “Yes, I’m coming,” she confirmed, “But isn’t there someone up there who is going to tell me what to do? Don’t let them say just: ‘Do some Latin Prose.’ Latin Prose is Greek to me; I never should know how to set about it. They say it is dreadful. But I’m not afraid of it…. Then there is some algebra. I wish you would forget all about that algebra. I hate algebra.” Two days later, the dean replied with an idea: “In making this plan I have in mind the use of your Barnard work as a cloak for some temporary disability in the entrance work. By the fall of 1914 we shall hope that there will be no need of any cloak.” Elizabeth Hazleton Haight’s tutelage by correspondence in Latin prose was doubtless part of Dean McCaleb’s plan, and it is likely that the deferral of further study of mathematics until Vincent’s freshman year was part of the “cloak.” Three days later, Vincent responded: “You wrote me such a nice, understanding letter. I didn’t know deans did.” Dean McCaleb’s last letter to Vincent, shortly before she came to Poughkeepsie, addressed her as “My dear child.”

The initial challenge in Vincent’s first days at Vassar in September 1913 were the dreaded entrance examinations in algebra, geometry and history. “It’s all right,” she wrote to Cora after taking them, “I belong here and I’m going to stay…. But Miss McCaleb says it doesn’t matter. I’m admitted anyway, if I flunk ‘em all…. So you can send my snowshoes.” She sent Kathleen the geometry examination: “Perhaps she can pass it. I couldn’t.”

Vincent passed the geometry exam, but not those in algebra or history: “I flunked—just flunked.” The failure in history was a particular shock, but Vincent’s rather glib text and the recollection of her examiner, Professor of History C. Mildred Thompson ’03, offer ample clarification. Millay had begun her six-page examination paper with breezy autobiography: ‘I was prepared in American History at my home in Camden, Maine, in the hammock, on the roof, and behind the stove. “ And she concluded it in apologetic flattery: “At this point the pleasant lady in an Alice-blue coat, who I wish might be my instructor in History, requests us all to bring our papers to a close. As I know a great deal about American History which I haven’t had a chance to say, I am sorry, but obedient.” Between these modes, her praise of Revolutionary War battles and heroes generously included some from the War of 1812. Thirty-eight years later, in 1951, Miss Thompson, who had saved the test papers, recalled that Vincent’s responses “were ‘at large’, and did not bear any particular relation to the questions asked…. The extraordinary information given at the beginning,” she admitted, “made me specially interested in the writer who was then unknown to me. When I was on the way to Miss McCaleb’s office to report the result of the examination. . . I met President Taylor. I remarked to him that I had just read a most remarkable history examination, remarkable but not for its knowledge of history. On looking at the name he exclaimed—‘Oh! Our poet!.’”

In her first year at Vassar Vincent roomed with a group of students in Mrs. McGlynn’s Cottage, one of a few off-campus accommodations used by the college, each with a resident “warden” and each with elected representatives in the various student organizations. Four years older than the other first year students; a notorious, published poet; and the eldest of three daughters of a financially hard-pressed nurse—in addition to her uneven academic preparation—Vincent was confronted with assimilation into the college’s populaces, habits and traditions and into the Class of 1917. This she undertook in an inimitably complex way.

One of her first student acquaintances, Agnes Rogers—“my sophomore…the most wonderful sophomore there is, they say,” she informed Cora—had written to her in August, “with real pleasure, having just read your ‘Renascence’ in ‘The Lyric Year.’” “How very proud Vassar and 1917 will be,” the sophomore said, “and how you will be pounced upon by ‘Miscellany’ people—the ‘Miscellany, is the college Magazine you know.” Rogers saw Vincent, she told Nancy Milford, as “one of the celebrities. And, well I think she liked it. She wasn’t really pretty…she was luminous, as if there were a light behind her…. I felt it. Everyone did.”

Another new acquaintance, her German teacher Florence Jenney, remembered seeing in the early days an exceptional person and student in Vincent. “Running footsteps overtook mine on the path between Rockefeller Hall and the Quadrangle,” she recalled, “and a slight figure paused beside me…. ‘I just wanted to say something to you,’ a rich, vibrant voice began. ‘I am going to love German. I know my work has not been very good yet, but it is going to be. By Christmas I shall be the best in the class.’” Jenney, who saw “a startling…instinct for self-protection” in Vincent, said, about her promise to be the best: “She was, easily. And by Thanksgiving, not Christmas. The incident was significant. There was nothing of conceit in her statement, no undue ambition. She had taken the measure of the members of the class and was fully aware of her own.” Miss Jenner also recalled a conversation in which Vincent “explained to me why she did not keep all the rules. She could not take them seriously…. It was hard to realize that things that her mother had always let her do were not allowed.”

Vincent’s letters at this time, largely to her family back in Maine, reflect enthusiasm and keen, always wary, observation. “All the girls here at McGlynn’s, about 30, like me, I know,” she told them, “they all want blankets like mine—and fo’ de Lawd’s sake listen—they make fun of me because I have so many clothes!!!!” Telling her family in November about the several girls who dressed as men, she noted, “They give themselves away, all right…. Catharine Filene, who took the flash, is in the middle of the other picture. Doesn’t she make a wonderful boy? Had two dances with him, and he wanted another.” Joining Miss Dow, as her protégé, for lunch at the president’s house, Vincent met Dean McCaleb: “Miss McCaleb knows,” she told her mother, “but you’re glad, aren’t you. I am…. She kissed me hello right before ‘em all, to show ‘em all she loved me, and then she kissed me good-bye just only before me, to show me she loved me. She’s a perfect darling.”

But in December, when Vincent told Arthur Ficke she wouldn’t be able to read his new play, Mr. Faust, until after her examinations, thus provoking a taunt from him, she fired back a much-quoted and misinterpreted account of Vassar and her life there. “Vassar College has won!,” Ficke had written, “It has tamed the wild spirit of Vincent Millay!

Now uttereth she no more little songs with wings,

But trafficeth with wisdom only.

O melancholy days of Vincent Millay’s downgoing. . .

The mighty have fallen.”

“Let me tell you something,” Vincent retorted, “Don’t worry about my little songs with wings; or about any of my startling & original characteristics….

“I hate this pink-and-gray college. If there had been a college in Alice in Wonderland, it would be this college. Every morning when I awake I swear, I say, ‘Damn this pink-and-gray college,’

“It isn’t on the Hudson. They lied to me. It isn’t anywhere near the Hudson. Every path in Poughkeepsie ends in a heap of cans and rubbish.

“They treat us like an orphan asylum. They impose on us a hundred ways and then bring on the ice cream—And I hate ice cream.

“They trust us with everything but men,—and they let us see it, so that it’s worse than not trusting us at all. We can go to the candy-kitchen & take what we like and pay or not, and nobody is there to know. But a man is forbidden as if he were an apple.”

Vincent spent most of the Christmas break of her freshman year—along again with Arthur Hooley and, particularly, Witter Brynner—with the Kennerleys in Mamaroneck. She told her “Dear ‘dored Family” of Brynner’s appreciation of her “beautiful speaking voice.” “He really was fascinated listening to me. (Sounds so silly, but gosh! Its [sic] dead earnest) . . .Oh, girls, I have wanted Witter Brynner to really—put down his paper & look at me—and now he has.”

In January, facing her first mid-year examinations, Vincent sent a not quite grim prophecy to her family. “Dearest Family— These are my parting words. Next week is mid-years and if I perish I perish. I shall flunk everything but French and that only because no one in the French department would have the nerve to flunk me,—after promoting me & putting me in the French Club, and having me write poems and a’ that….

“O, about flunking my exams,—I shall flunk History & probably Geometry, and I may pass German and possibly Old English. That’s the way I stand at present. I’m going to cram some, but, darn it, I’m tired. If I flunk ‘em all they won’t send me home, because two of ‘em are Sophomore courses and oh, well, they wouldn’t.”

They didn’t, and Vincent didn’t flunk anything. Along with A grades in French and German, her other grades were B in English, B- in history, and C in the dreaded Geometry—almost a mirror of her performance in her seven subsequent semesters, with the exception of Social Psychology, in her last semester, in which Professor Margaret Floy Washburn ’91 awarded her a D.

In “Vincent at Vassar,” Elizabeth Hazelton Haight gave an expert analysis of Vincent’s academic program: “Vincent fulfilled all [the required] conditions and then built her course around her own interest. English studies were its foundation, and they included a wide range and great teachers: Old English and Chaucer with Christabel Fiske, Nineteenth Century Poetry, and Later Victorian Poetry, an advance[d] writing course with Katherine Taylor, English Drama with Henry Noble MacCracken, The Techniques of Drama with Gertrude Buck, who started the Vassar Theater. Then she enriched her knowledge of literature with many courses in foreign languages, Greek and Latin, French, German, Italian, and Spanish. Besides the course in General European History, she elected Lucy Maynard Salmon’s course in ‘Periodical Literature: Its Use As Historical Material.’ And she had a semester in Modern Art with Oliver Tonks, one in Social Psychology with Margaret Washburn, one in Music.”

—————

As Vincent entered her second semester at Vassar she was at once both more relaxed and more engaged. At the very end of the previous term, she had agreed to write a farewell song for Georgianna Conrow, who was leaving the French department for a semester abroad. Set to the tune of “Au Clair de la Lune,” the lyrics, Agnes Rogers reported to Vincent, had prompted the formidable Professor Jean Charlemagne Bracq to exclaim “C’est exquis!” Vincent sent the professor’s praise and the song to Cora. “Remember,” she reminded her mother, “that in singing the final e’s are pronounced: ‘O, Journée obscure-e’ e—uh.“

In January the Miscellany News announced a competition offering four prizes of 15 dollars each to students submitting the best poem, story, essay or play. Vincent told Cora she was submitting a story she’d written at Barnard, “Barbara at the Beach,” and “Interim,” the 209-line poem on loss she had long been at work on. “It might help me get a scholarship next year,” she wrote, “& anyway it would undoubtedly smooth things out for me here. On the days when I didn’t have my lessons people would think—instructors especially—‘O well, she’s been writing a poem.’” Six weeks later she again justified to Cora submitting the poem: “It would be a bigger hit in a college full of women than anywhere else in the world and might do a lot for me.” “After all,” she concluded, “I shall write other poems, better than that, or I’m not much good.”

As the semester progressed Vincent found herself writing to her family less often and at lesser length. In an undated letter she explained: “All that keeps me from writing long, long letters about Vassar is that I’m getting so crazy about Vassar & so wrapped up in Vassar doings, that I don’t have so much time as I used to have when I just liked it well enough…. But oh, I love my college, my college, my college!” She described joining, with friends, “Last night by the light of the moon,” some seniors “& some others we knew…strumming the mandolin & singing” in the bleachers of the Athletic Circle. “& the moon shined bright as day & the warm wind blowed, & oh, didn’t we love our college!—I thought—Lord love you—‘If Mother could see me now!’

“Now, lemme go, I gotta study—or they won’t let me stay.”

As her first year at Vassar came to a close, Vincent looked forward to residence on campus the following semester. Her room in the new residence hall—known simply as North until it became Jewett House in 1915—was, she wrote her mother on May 7, 1914, “a perfectly wonderful single…a corner room with two windows & lots of room for everything…. Catherine Filene & Harry [Harriet Weifenbach ’17] are right down the stairs from me…& they both send their love…. I shall have the cutest room.” A few days later, she wrote enthusiastically to Norma about her class’s acceptance of the marching song she had written. “& day before yesterday was Sophomore Tree Ceremonies—I’ll send you a program (I was on the committee, you know, and wrote all the words—to Grieg & Tschaiwoski [sic] (!) tunes) and after the ceremonies, the best they ever had here, people say, the class marched all around campus for hours singing their Marching Song for the first time. It’s a custom. Everybody’s mad about it…. God help me in my exams. “

The end of Vincent’s first year at college was the beginning of a succession of extracurricular accomplishments and recognition. A notice in the May 22 issue of the Vassar Miscellany announced that Vincent’s submission in the prize contest, her long poem “Interim,” was the winner. Despite what the judges called “uneven” execution and occasional “metrical lawlessness,” and although they suggested the poem’s “dimension is perhaps greater than its real content,” the prize “was awarded to Interim on the basis of its direct and powerful imaginative appeal.” Vincent’s happy letter to Cora urged her mother, first, not to “feel bad that I let it go for so little. I shall do more, much better, or it won’t matter.” “And,” she continued, “it will mean a great deal to me here, both with the faculty & the girls. Please don’t mind, dear.”

—————

As a child of five, concurrently with the reading of poetry, Vincent had begun performing in public, and the fall after her graduation from high school she had secured the lead in a traveling stock company where her skills won her a promise from the company’s producer and director of a permanent appointment, if and when the company was able to operate on a solid basis. Although that never happened, she had remained convinced of her thespian abilities, and the few such opportunities that had come her way had confirmed her confidence.

She was delighted when, in the fall of 1914, she was cast as the Princess in the Sophomore Class Play, part of the annual Sophomore Party for the freshman class. “You don’t really know how important it is to be a big thing in Sophomore Party,” she told her family. “All the Freshmen will know me as the Princess afterward. And some of the Juniors are ushers, so they’ll be there. And all the faculty.” A bit later, as rehearsals were drawing to a close, she wrote, “I’m the whole show!—Guess if I’m enjoying myself.”

Acclaimed maladroitly in the Vassar Miscellany as the “most unique Sophomore Party in the history of Vassar,” the play was said to be “unusually good in several ways.” As Princess Primrose Violet Daisy Hawthorn Honeysuckle Hohen-Stuart, Vincent held the audience “in delighted appreciation.” “After it was over even the Faculty congratulated me,” she told her family, “and the girls,—I can’t tell you the things they said, but it’s been a wonderful thing for me. Everywhere on campus now I meet people who say ‘Hello, Princess!’ & yesterday, actually, in the laboratory, with many girls experimenting all around us, Professor [of Physics Frederick A.] Saunders came up to me & said, ‘How is your Royal Highness this afternoon?’ And then he said, ‘I want to thank you for what you did for us Saturday. It was very lovely.’”

Vincent’s charismatic presence in body, voice and gesture was “obvious and intense,“ her classmate and friend Virginia Kirkus Glick ’16 told Nancy Milford in 1980, “and I think she enjoyed it largely…. She was a natural subject. She was different from others, from the rest of us. She had an elusive, physical charm which we didn’t associate with our sex in those days. I think I was naïve. I was matter-of-fact. Vincent wasn’t matter-of-fact about anything.”

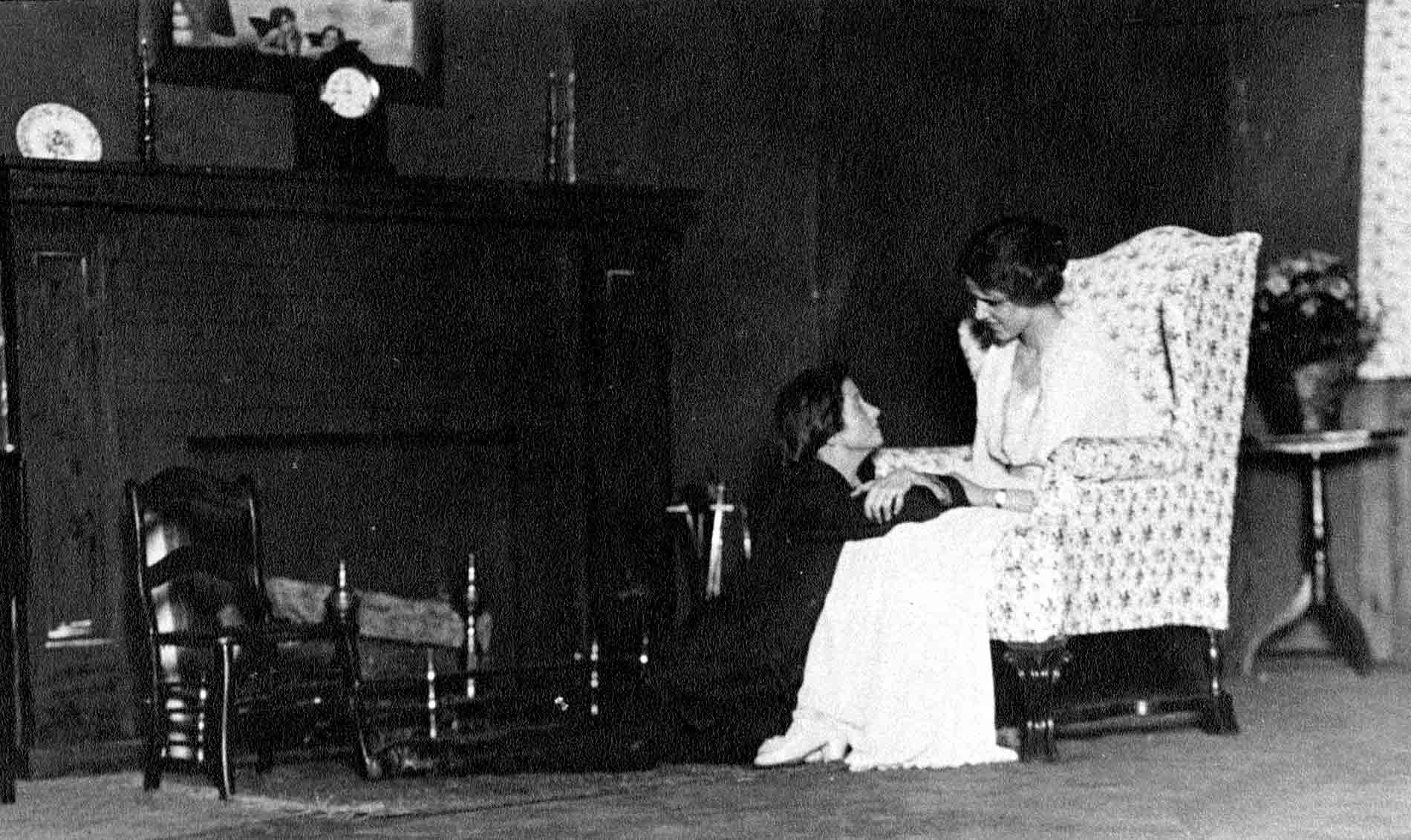

Vincent’s next performance, the following March, was similarly a success but in an entirely different and probably more challenging role, that of Eugene Marchbanks in the Second Hall Play, Bernard Shaw’s Candida. She was praised again in the Vassar Miscellany as one of the two actors who “achieved a real conception of the possibilities of their parts.” “The audience,” the reviewer wrote, “never lost a sense of Marchbanks’ [sic] personality as a whole, its weakness, its strength, its lack of common sense and its grasp of the values of life. Every expression and gesture of his was full of restraint and exact appropriateness. From first to last he dominated the stage.” Two days later Vincent reported to “Dear darling adored Family” that “A great many people said I made them cry. And certainly in other places I made them laugh.—It’s a queer part, you know, of a boy of eighteen, a poet terribly sensitive to situations and atmosphere, in love with the wife of an English clergyman.”

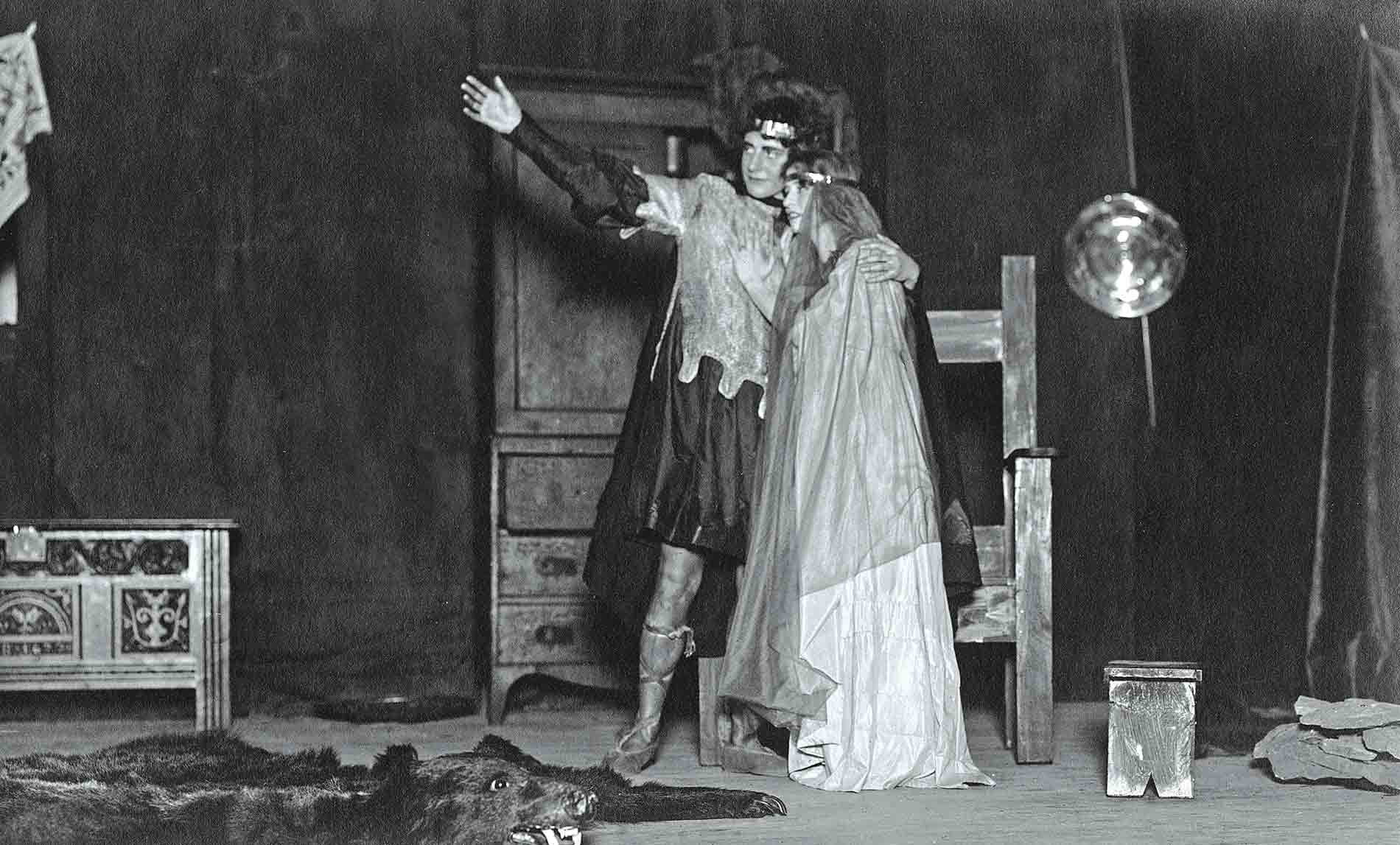

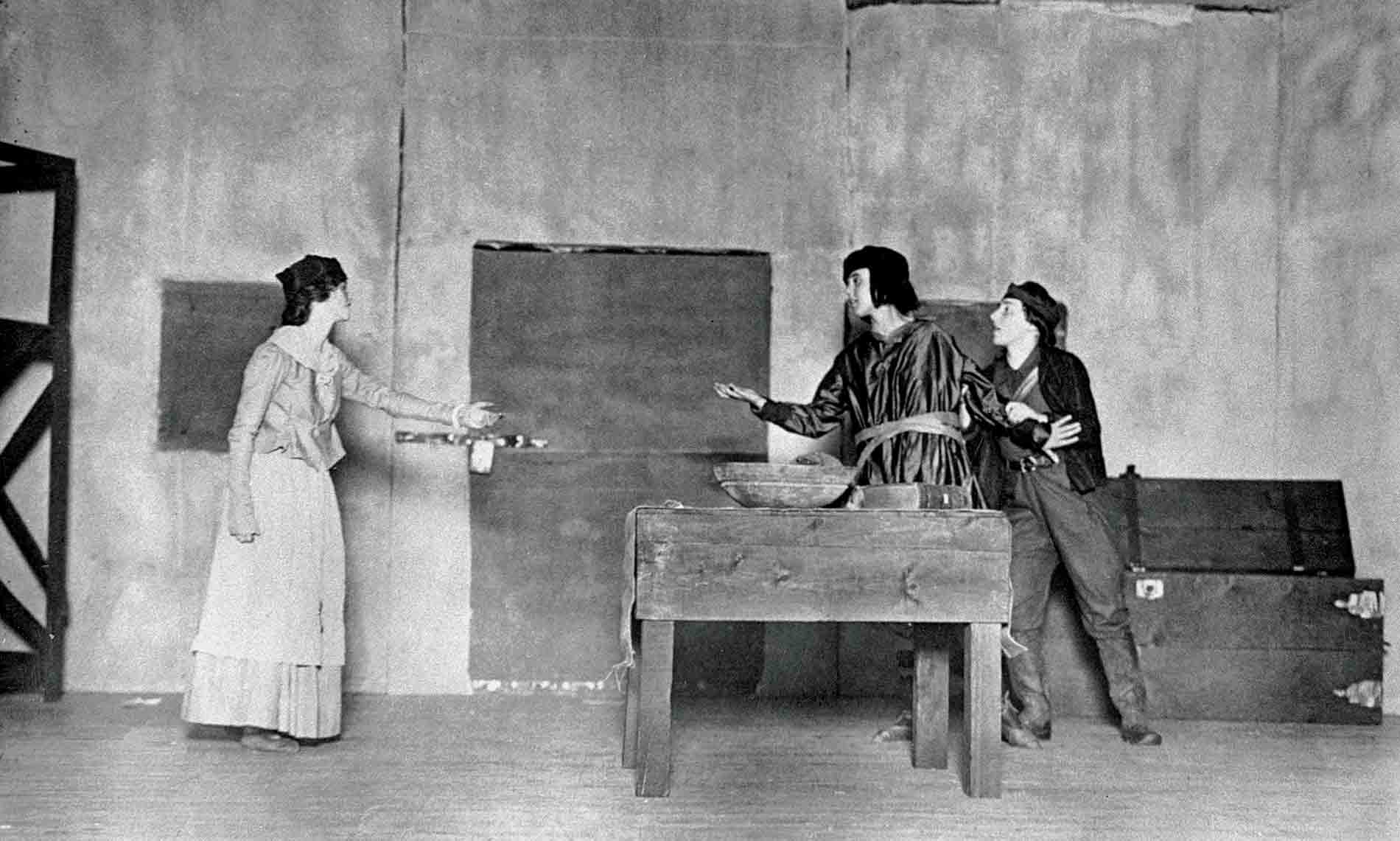

Vincent’s portrayal in March 1916 of the title character in the Second Hall Play, Synge’s Deirdre of the Sorrows, again brought praise for her “vital, artistic, colorful” interpretation. “Her really unusual ability,” the reviewer noted, “swung the rest of the cast into more vivid action, and brought out all the glamour and charm of the play itself.” At the start of her final semester, she similarly led in another role, that of Vigdis Goddi, in John Masefield’s The Locked Chest, one of three one-act plays presented by Philaletheis in January 1917. A reviewer in Vassar Quarterly, calling the play “the undoubted triumph of the evening, “ said “Vigdis Goddi, wife of Thord, carried the audience with her from the first. She looked the part of the unusual peasant woman, finer grained than most and with fire.”

As Vincent continued her involvement with student theatrics at Vassar, the college was beginning to develop, through the efforts of Professor of English Gertrude Buck, one of the first collegiate academic programs in drama. Vincent was a student in 1916 in course U, Miss Buck’s “Techniques in Drama,” and in her Vassar Dramatic Workshop, the first such undertakings at a woman’s college. One of the two plays Vincent composed in the workshop, “The Princess Marries the Page,” was among three plays presented and critiqued at Vassar on Saturday, May 12, 1917. Vincent played the princess in this production, in one in October at The Bennett School in Millbrook, New York, and, later that fall, in the play’s New York City premiere at the Provincetown Playhouse. Her other workshop play was “The King and Two Slatterns.”

Vincent’s most vivid performance may have been that given as part of an elaborate dual observation on October 10-13, 1915, of Vassar’s 50th anniversary and of the inauguration of its fifth president, Henry Noble MacCracken. Set amidst addresses, receptions, presentations, business meetings, two sessions of an intercollegiate student conference—discussing “The Function of Non-Academic Activities—and two concerts by the Russian Symphony Orchestra, “The Pageant of Athena,” composed by students under the direction of the suffragist and pageant producer Hazel Mackaye, was presented twice in the new Out-of-Door Theatre constructed specially for this event. The pageant, in which some 400 students took part, started with the invocation to the Greek goddess of wisdom, Pallas Athena—the deity presented on Vassar’s seal—which was followed by a series of dramatic scenes portraying a history of “learned women” and of their influence in diverse public spheres. The archaic Greek poet Sappho was followed by: the Roman orator Hortensia; the seventh century British abbess Hilda of Whitby; Marie de France, in the 12th century, the first French woman poet; Isabella d’Este, a cultural and political leader in the Italian Renaissance; the 16th century humanist and, briefly, English queen, Lady Jane Grey; and the 17th century Venetian polymath Elena Lucrezia Cornaro, the first woman to receive a doctorate, an achievement celebrated in the great west window of Vassar’s Frederick Ferris Thompson Memorial Library.

Mary Simonson, in Body Knowledge: Performance, Intermediality, and American Entertainment at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, sees in “The Pageant of Athena” a reversal of contemporary notions of the past and of antiquity in the portrayal of Sappho and Hortensia as “no less civilized than Elena Cornaro or the Vassar Students themselves.” Thus Vincent as Marie de France, profoundly calm in the presence of Henry II and Queen Eleanor, responds to the King’s qualms about a woman who is both a scribe and a poet, saying “I bethought me of the lays that I had heard sung in remembrance of adventure, and since I would not leave them forgotten in the world, I rhymed them into verse. And as I set them down on parchment, the words inscribed themselves upon my heart.” She then recites Marie’s “Chevrefoil,” her poetic correlation of the calamity of Tristan and Isolde with the honeysuckle and the hazel branch. Calling the pageant a “Wonderful Spectacle,” the Poughkeepsie Eagle described Vincent’s performance: “Into a scene of courtly beauty, where stately ladies and gallant cavaliers are dancing the minuet, came a dainty little figure, slight and dainty even in a dress of white satin with a train so big that two pages were needed to carry it …. Her grace was as great as her learning. So noble ladies and great lords listened…as the girl from France told her stories of love and hate and fighting.”

The conclusion of the pageant, as told by the event’s “chronicler,” Constance Mayfield Rourke ’07, reinforces Mary Simonson’s notion. At the end of the Cornaro episode, the singing of the Gaudeamus igitur by the celebrating students of Padua dies down as Athena reenters, as do the preceding “learned women” and their companions. Once again, the Gaudeamusof the students of Padua sounds and starts to fade, but “the echo grows in power, the Gaudeamus again becomes clear, and a great throng of singing girls, bright-clad in the costumes of today, stream down the slope and singing pass in a long procession before the goddess, their song changing to the new Alma Mater as they march.

“They too wind away. Their song grows faint and is lost. Dusk has fallen. The priestesses silently depart. There is a flare of light, a cloud of smoke, and Athena vanishes, slowly and alone.”

—————

The retiring President James Monroe Taylor may have heard of “our poet” in passing, but his successor, Henry Noble MacCracken, whose inauguration was the second reason for the grand celebration in October 1915, came to know her quite quickly and quite well during Vincent’s last four semesters at Vassar. Speaking in November 1966 to an interviewer from the Vassarion, the college’s yearbook, he allowed that Vincent had been one of his students, “but of course I knew her better outside than in.” To the interviewer’s question about Vincent’s reputed frequent absences from class, MacCracken responded, “She cut everything. I once called her in and told her, ‘I want you to know that you couldn’t break any rule that would make me vote for your expulsion. I don’t want any dead Shelleys on my doorstep and I don’t care what you do.’ She went to the window and looked out and said, ‘well, on those terms I think I can continue to live in this hellhole.’”

Prompted by Mrs. MacCracken to “tell them about the time she failed to come to one of your classes because she was ill,” MacCracken complied. “In those days students could absent themselves whenever they pleased and just send in a sick excuse. I stopped her in the hall one of those times and said, ‘Vincent, you sent in a sick excuse at nine o’clock this morning and at ten o’clock I happened to look out the window of my office and you were trying to kick out the light in the chandelier on top of Taylor Hall arch, which seemed a rather lively exercise for someone so taken with illness.’ She looked very solemnly at me and said to me, ‘Prexy, at the moment of your class, I was in pain with a poem.’ What could you do with a girl like that?” Asked if Vincent had been the sort of student who wrote poetry in class, a daydreamer, Prexy responded, “She wasn’t a daydreamer, she was much too lively for that; it’s rather absurd. It was like a volcano explosion when she got an idea.”

MacCracken also clarified Vincent’s D grade from Professor Washburn in her last semester. “[Miss] Washburn, who is one of the most fair-minded women you ever saw, and a great teacher—one of our really great teachers—came into my office and threw this essay on my desk and said ‘Read that. Look at that. That young scoundrel has cut my classes all the semester, practically, yet she lives on strong coffee for the last four days and comes in and get an A+ on her exam; and this paper—you can’t give it any less than that. I don’t know how much time she spent on it, but there it is.’”

Toward the end of the interview MacCracken noted the autobiographical nature of one of Vincent’s plays, inspired by a discussion in his class of morality plays. The play, he noted, had been performed widely, and Millay was known, decades later, to conclude her public readings with it. The idea “came to her that she would do a play about herself. She had always wanted to do that so she wrote this King and Two Slatterns. You see she was two persons: she was very slatternly most of the time; she looked as if she ought to be thrown in the ash can and on the other hand she was neat and exquisite and fantastic in her makeup. Both by turn; just so in this play she wrote in my class. (She didn’t listen to my next two or three lectures. She just dashed off this play.)”

—————

With the exception of Professor Washburn’s class, Vincent’s senior year went along very well—in English courses with President MacCracken and Gertrude Buck, in art, in more Spanish, and in Italian, thus rounding out study in all the languages, classical or modern, taught at the college. “Excuse everything,” she had written to the “Darlings” at home as her final semester got underway, “I am cramming as I have never crammed before in all my crammous days for my baby Italian exam—I am actually learning the whole grammar by heart…& my mind is on you—I shall be with you—but do you mind if under these most ‘straordinary scumstances I study in your presence?” Her literary life was also still ‘straordinary; in the same hurried letter she announced, “I have something nice to tell you—I had a letter a few days ago from no less a person than John Masefield—he says that a great many of his friends have written him, telling him how wonderful I was as Vigdis & he wishes he could have been here. He says I am the first person ever to play Vidgis—it is quite new, you know….The letter was so exciting. It said ‘Opened by Censor’ on it.”

Vincent and Vassar were soon to both clash and, with Prexy’s help, collaborate in the drama surrounding an event at the very end of her time at the college. As spring and graduation approached she had been given the honor of writing the words and music for the Baccalaureate Hymn, traditionally sung at the ceremony preceding Commencement. The result, a compact, poised and challenging prayer, was a great success:

“Thou great offended God of love and kindness,

We have denied, we have forgotten Thee!

With deafer sense endow, enlighten us with blindness,

Who, having ears and eyes, nor hear nor see.

Bright are the banners of the tents of laughter;

Shunned is Thy temple,—weeds are on the path;

Yet if Thou leave us, Lord, what help is ours thereafter?—

Be with us still,—light not to-day Thy wrath!

Dark were the ways where of ourselves we sought Thee,

Anguish, Derision, Doubt, Desire and Mirth;

Twisted, obscure, unlovely, Lord, the gifts we brought Thee,

Teach us what ways have light, what gifts have worth.

Since we are dust, how shall we not betray Thee?

Still blows about the world the ancient wind—

Nor yet for lives untried and tearless would we pray Thee:

Lord let us suffer that we may grow kind!

“Lord, Lord!” we cried of old, who now before Thee,

Stricken with prayer, shaken with praise, are dumb;

Father accept our worship when we least adore Thee,

And when we call Thee not, oh, hear and come!

But the hymn’s composer and author was banned from its performance.

On May 21 Vincent had written joyously to her family about her “beautiful motor trip yesterday & today,—50 miles today—don’t know how far yesterday. Beautiful!—some friends…girls. Four of us in a little Saxon—stayed all night at the house of one.” On June 6, however, in a letter beginning “In a few days now I shall write myself A.B.,” she revealed “something unpleasant but quite unimportant that has just occurred…. the Faculty has taken away from me my part in Commencement.—That doesn’t mean what is says, because my part in Commencement will go on without me,—Baccalaureate Hymn, for instance, or the words of Tree Ceremonies, which we repeat—& all the songs & our marching songs which will grace the final activities…. I can’t graduate with my class,—my diploma will be shipped to me, as I told Miss Haight, ‘like a codfish’…. I always said, you remember, that I had come in over the fence & would probably leave the same way.—Well, that’s what I’m doing . I don’t pretend that I don’t feel badly—I have wept gallons, —all over everybody…. It isn’t a disgrace, you see, folks,—it’s just a darned unpleasant penalty for carelessness of college rules, occurring at a darned unfortunate time. But I never knew before that I had so many friends.—Everybody is wonderful.”

Owing probably to an accumulation of broken or flouted rules and regulations, Vincent had recently been “campused,” the Vassar wardens’ term for having lost the privilege of nights away from the college. The night at her friend’s house, already a breach of this limitation, was made worse by her light-heartedly signing a guest register at the Watson Hollow Inn near the Ashokan Resevoir in the Catskills, where the group had stopped on May 21 to eat. By an uncanny coincidence, one of the college wardens, lunching later at the inn, happened to look at the register, see Vincent’s signature—below that of a man!—and report all this to her superiors. “The Faculty voted to suspend her indefinitely,” Miss Haight recalled, “This meant the loss of her degree. Faculty and friends were indignant. Dr. Elizabeth Thelberg, the college physician…proclaimed irately, ‘I wrote my name under Lord Kitchener’s at Shepheard’s Hotel in Cairo, and nobody thought the worse of me’…. President MacCracken saved the day.”

“The faculty was just in a rage about it,“ President MacCracken remembered 50 years later, “I didn’t do anything at the time, because I thought their heat would die down. I quietly slipped a word in to the President of the Senior Class that I thought a petition for her reinstatement might be favorably considered…. The President of the Class got a petition signed by practically every girl in the class.1 I then had it manifolded and sent out to the Faculty. I did not insult them by insisting on a special meeting over Vincent.” Instead, MacCracken’s approach was to draw his colleagues’ attention to the fact that all the undersigned students were certified as graduates and that their “opinions should receive some consideration.” The petition, MacCracken said in his letter to the faculty, “is accompanied by letters from eighteen individuals urging, first, that the penalty imposed is too severe…second, that false rumors regarding her reputation would be nullified by allowing her to remain and take her degree with the Class. Do you favor granting this petition by allowing suspension to end Saturday night? Please answer yes or no.”

“A large majority of the faculty signed,” MacCracken recalled, “and I immediately cancelled the suspension. By that time the hymn she had composed for the baccalaureate Sunday had been sung. But she came back for Commencement. Vincent stayed as our guest before Commencement because I thought it better not to provoke some insult or other by having her stay in the dormitories.”

Just after her graduation, Vincent wrote to Norma from New York City: “Tell Mother it is all right—the class made such a fuss that they let me come back, & I graduated in my cap and gown along with the rest…. Commencement went off beautifully & and I had a wonderful time. Tell her this at once if you can….

I am feeling much rested,—& all keyed up to go to work—but, oh, I am so homesick to see you, dear & Mother,—& the garden & everything!—Never mind, If I have good luck I shall come home,—unless I have to begin work at once.

“Please write my darling, darling, darling sister.

Vincent

Edna St. Vincent Millay A. B.!”

—————

1 Elizabeth Hazelton Haight and Nancy Milford put the number of signatories at 108; out of 237 graduates, about 46%.

Sources

Daniel Mark Epstein, What Lips My Lips Have Kissed: The Loves and Love Poems of Edna St. Vincent Millay, Henry Holt and Company, 2001.

Florence C. Jenner, “As I Remember Her,” Russell Sage Alumnae Quarterly, Winter, 1951.

X. J. Kennedy, “Edna St. Vincent Millay’s Doubly Burning Candles,” The New Criterion, Sept. 2001

Allen Ross Macdougall, Letters of Edna St. Vincent Millay, Harper & Brothers, 1952.

Nancy Milford, Savage Beauty, Random House, 2001.

Constance Mayfield Rourke, The Fiftieth Anniversary of The Opening of Vassar College: A Record, Vassar College, 1916.

Mary Simonson, Body Knowledge: Performance, Intermediality, and American Entertainment at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, Oxford University Press, 2013.

Interview with Henry Noble MacCracken, Vassarion, 1967.

“The First Hall Play,” Vassar Quarterly, vol. II, no. 2, 1 February 1917.

“Baccalaureate Hymn, by Edna St. Vincent Millay,” Vassar Quarterly, vol. II, no.4, 1 July,1917.

Elizabeth Hazelton Haight, “Vincent at Vassar,” Vassar Quarterly, vol. XXXVI, no. 5, May 1951.

“Report of the Judges of the Miscellany Prize Contest,” Vassar Miscellany Weekly, vol. 1, no. 13, 22 May 1914.

“Sophomore Party,” Vassar Miscellany, vol. II, no. 6, 30 October 1914.

“Candida: A Pleasant Play by Bernard Shaw,” Vassar Miscellany, vol. XLIV, no. 10, 12 March 1915.

“Deirdre of the Sorrows,” Vassar Miscellany Weekly, vol. 1, Number 23, 17 March 1916.”

“Founder’s Day,” Vassar Miscellany Weekly, vol. 1, no. 29, 12 May 1916.