Shakespeare at Vassar

Shakespeare in Drawings and Paintings from the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center

by Elizabeth Nogrady

The Andrew W. Mellon Curator of Academic Programs

Writing to her father on October 24, 1865, Vassar student Helen Sylvester complained, “I am sure I do not know what we have to use Shakespeare and Milton for, but I suppose they will come in time into use.”1 Helen’s opinion aside, she wrote her missive a month after Vassar opened its doors to students, revealing that, from the outset, Shakespeare was an integral part of the curriculum. Tracing the thread of Shakespeare woven through the fabric of Vassar’s intellectual and cultural life leads to a consideration of the college’s art collection. Drawings and paintings related to Shakespeare, housed today at the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, date primarily from the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Shakespeare subjects in fine art proliferated in the wake of the Jubilee of 1769 in Stratford-upon-Avon commemorating the bicentennial of Shakespeare’s birth. The trend continued into the mid-nineteenth century, when a number of such works came to Vassar as part of the founding gift presented by Matthew Vassar, and continued to enter the permanent collection in subsequent years.2 These drawings and paintings can be used to explore the phenomenon of Shakespeare in art as it originated in Britain and spread to the United States, eventually becoming a vital part of the Vassar College art collection.

One eighteenth-century scene from Shakespeare in the Art Center’s collection is Joan of Arc and the Furies (Figure 10) by William Hamilton (1751–1801). This painting belonged to Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery, the seminal exhibition of Shakespeare-inspired paintings held at 52 Pall Mall in London’s West End beginning in 1789. The project was the brainchild of publisher, engraver, and alderman of the City of London John Boydell, who commissioned works by celebrated artists living in Britain such as Benjamin West, Angelica Kauffman, and Henry Fuseli.3 Boydell popularized the imagery through the publication of corresponding prints by professional printmakers.4 According to him, the undertaking was not simply a business proposition, but also a means to elevate the arts in Britain. Boydell contended that in his home country, “Historical painting is only in its Infancy” and that he sought “to advance that art towards maturity, and establish an English School of Historical Painting.”5 Shakespeare, by this time England’s most celebrated literary figure, proved the ideal nucleus for such a project.6

Also belonging to Vassar is a number of British drawings with subjects from Shakespeare formerly in the collection of Elias L. Magoon. Magoon was the Baptist minister, Vassar trustee, and chairman of the Art Gallery Committee who amassed a considerable art collection that he sold to Matthew Vassar, who in turn gave it to the college in 1864. 11 This group includes a number of Shakespeare works on paper. One is Hamlet and the Ghost of his Father from around 1799 (Figure 11) by James Northcote (1746–1831). Northcote, a student of Sir Joshua Reynolds, belonged to the cadre of younger artists who flourished as contributors to the Shakespeare Gallery.12 In this pen and ink sketch, Hamlet locks eyes with the decidedly non-ethereal ghost, who turns away, gesturing in an entreaty for Hamlet to follow him. A round full moon and hatching indicating a dark sky lend drama to the scene, as do the intent gazes of onlookers at left, Horatio and Marcellus. Also from Magoon are two highly theatrical drawings of The Marriage of Romeo and Juliet by George Cattermole (1800–1868), a watercolorist who mined British history for subject matter, and the historicized Shakespeare in his Study of 1854 by J. E. Buckley (active 1843–1861), an artist from whom Magoon directly commissioned works.13

American-born artists took up the Shakespeare theme as well, as is evidenced by The Death of Hotspur (Figure 12) by John Trumbull (1756–1843). Born in Connecticut, Trumbull traveled to London in 1780 to study with Benjamin West. In this finely wrought ink drawing, also from the Magoon collection, Henry, Prince of Wales, kneels in armor beside the wounded Harry Percy, called Hotspur. Text below the drawing in the artist’s hand excerpted from Henry IV, Part 1 confirms the scene.14 The work is dated 22 November 1786, a key moment in Trumbull’s career. Earlier that year, he had begun his celebrated painting The Declaration of Independence based on the account of Thomas Jefferson.15 In November, according to Trumbull’s autobiography, he returned to London and,

…went on with my studies of other subjects of the history of the Revolution, arranged carefully the composition for the Declaration of Independence, and prepared it for receiving the portraits, as I might meet with the distinguished men, who were present at that illustrious scene.16

In this period, Trumbull also repeatedly depicted Revolutionary-era battles, whose fallen figures recall the wounded Hotspur.17

Another Shakespeare-themed work by an American artist who spent time in England is Titania’s Fairie Court (Figure 13) by Washington Allston (1779–1843). Allston, who owned an eight-volume set of Shakespeare plays from 1799, borrowed subjects from Shakespeare throughout his career.18 He began this large-scale, unfinished canvas, based on A Midsummer Night’s Dream, around 1836 for Lord Morpeth (later the Earl of Carlisle) on behalf of his sister, the Duchess of Sutherland, for the outstanding sum of £5,000, or $25,000. In this work, Titania reclines languidly at left, identifiable through her crown and attendants, watching as her retinue dances and frolics in intertwined, almost weightless circles.19 Allston was apparently proud of the work, for he showed it regularly to visitors in his Cambridge, Massachusetts studio and spoke of it highly.20 Left incomplete at his death, the canvas provides a glimpse into Allston’s notoriously time-consuming working process of outlining his figures and then blocking in areas of wash.21 The work remained with Allston’s family after his death and hung in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, for many years, before being given by the Washington Allston Trust to the Vassar College Art Gallery in 1955.22

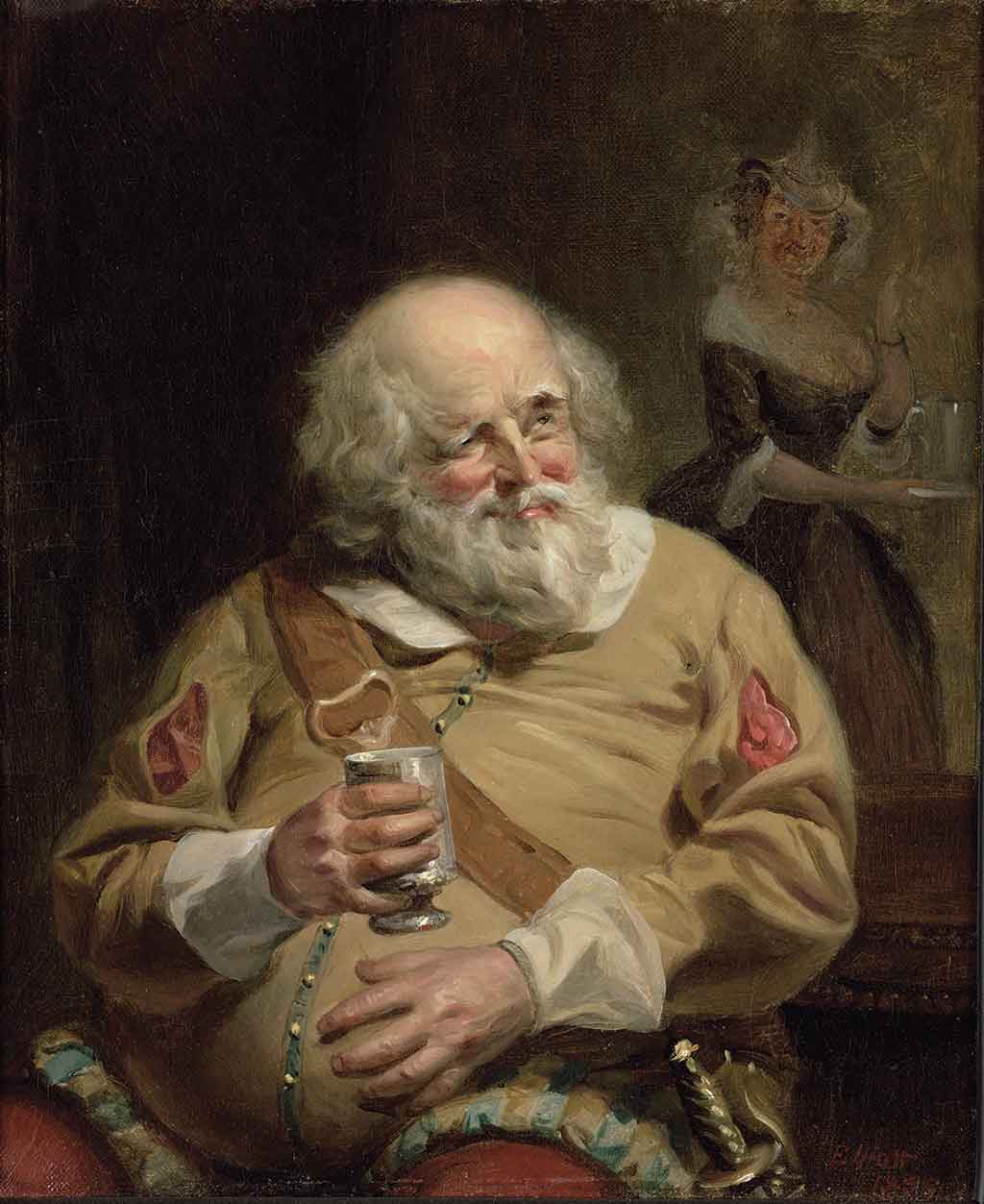

Later in 1856, New York artist Charles Loring Elliott (1812–1868) painted Falstaff (Figure 14).23 The subject is Sir John Falstaff, comic companion to Prince Henry, with roles in Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2, and The Merry Wives of Windsor. A favorite in paintings of this period, Falstaff appears with drink in hand, his ruddy face turned to cast a lascivious smile at Mistress Quickly, proprietor of the Boar’s Head Tavern.24 Formerly in the Magoon collection, this work has a literary subject, a rarity in Elliott’s portrait-dominated oeuvre. In 1867, Henry T. Tuckerman opined of this painting: “What an incarnation of jolly epicurism! How complacently his hand rests on his distended paunch, as if indicating the seat of the soul; what animal delight in the eye, what thorough sensual philosophy in the whole expression!”25 Elliott, who had studied with John Trumbull, strengthened his connection to Vassar in 1861, after the Board of Trustees commissioned him to paint a full-length portrait of Matthew Vassar, now a mainstay of the collection.26

Also common in nineteenth-century works of art are representations of Shakespeare’s hometown of Stratford-upon-Avon, a popular tourist destination in the 1800s.27 The most compelling example at Vassar is The Shrine of Shakespeare of 1859 (Figure 15) by Sanford Robinson Gifford (1823–1880). On the small-scale canvas is a view of Holy Trinity church nestled in the trees beside the glittering River Avon, populated by a white swan as a woman in a red shawl promenades nearby. Gifford, born in Greenfield, New York, visited Stratford in July 1855 and provided a dramatic account of visiting Shakespeare’s grave.28 He also recounts recording the site, writing: “This Church is beautifully situated on the banks of a small river. It is large and handsome and is shaded by noble elms, I made a sketch from a further bank.”29 Presumably, he later used this sketch to create the painting, dated 1859, for Magoon, who collected multiple works by the artist.30

In the earliest days of the college, Matthew Vassar wrote to Magoon articulating their shared belief that the “special purpose” of Vassar’s art gallery, “should be to elevate and involve the minds of the

pupils. . .”31 Works of art with Shakespeare subjects fulfill this aim, aligning as they do with other aspects of the curriculum. More broadly, identifying this group of works in the Art Center’s collection demonstrates how art, alongside literature and drama, helped to root Shakespeare so firmly in American education and at Vassar College in particular.

I would like to thank Jason LaFountain, G. Joseph Bettman, Margaret Vetare, and Patricia Phagan for their assistance in researching and editing this essay.

NOTES

1 Helen Sylvester (Seymour), 24 October 1865, Student Letters, Archives and Special Collections Library, Vassar College Libraries.

2 For information on Shakespeare in fine art, see Jane Martineau et al., Shakespeare in Art, exhibition catalogue, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, 2003; and Richard Studing, Shakespeare in American Painting (Rutherford, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press; London: Associated University Presses), 1993.

3 See Rosie Dias, Exhibiting Englishness: John Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery and the Formation of a National Aesthetic (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013).

4 For Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery prints in the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, see accession numbers 1968.25.1–.6; 1969.10.1.1–.99.

5 John Boydell, A catalogue of the pictures, &c., in the Shakspeare Gallery, Pall-Mall (London, 1793), v. See also Dias, “Creating a Space for British Art,” Chapter 1, in Exhibiting Englishness, 17–63.

6 In the words of William L. Pressly, Shakespeare was for eighteenth-century British artists “proof that original genius was native to the soil.” See Pressly, The Artist as Original Genius: Shakespeare’s “Fine Frenzy” in Late-Eighteenth-Century British Art (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2007), 30.

7 Hamilton was second only to Robert Smirke in completing paintings for the Gallery. See William L. Pressly, A Catalogue of Paintings in the Folger Shakespeare Library (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 69.

8 Depicted in this work is Act V, Scene 3, when Joan La Pucelle declares, “See, they forsake me! Now the time is come/That France must vail her lofty-plumed crest/And let her head fall into England’s lap/My ancient incantations are too weak,/And hell too strong for me to buckle with:/Now, France, thy glory droopeth to the dust.” In 1795, Boydell published an engraving of this work by Anker Smith after Hamilton. See also John Christian, Shakespeare in Western Art, exhibition catalogue, Isetan Museum of Art, Tokyo, 1992, no. 30.

9 Boydell suffered a bankruptcy in 1803 and the gallery disbanded in 1805, which he attributed to the contracting print market in continental Europe due to the Napoleonic wars. The paintings were subjected to a lottery, then sold at auction. For Joan of Arc, see Boydell Gallery sale, Christie’s, London, 17 May 1805, lot 29.

10 McCormick thought this painting “…would add a certain distinction and character to our collection.” See Correspondence, Thomas J. McCormick to Mrs. Archie Botson, 7 June 1966, Object Files, Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center.

11 See Matthew Vassar, Communications to the Board of trustees of Vassar College. By its founder (New York: J.A. Gray & Green, 1869), 28; Patricia Phagan, “Drawings at Vassar to ‘Illustrate the Loftiest Principles and Refine the Most Delighted Hearts,’” Master Drawings 42, no. 2 (Summer 2004): 133–144.

12 Boydell commissioned eight paintings from Northcote, none of which correspond to this drawing. See Martineau, Shakespeare in Art, 99; and Dias, Exhibiting Englishness, 110.

13 Cattermole worked with John Britton, the antiquarian and publisher from whom Magoon acquired many drawings for his collection (see accession numbers 1864.2.2951 and 1864.2.2952). Themes related to Shakespeare fit squarely with Magoon’s taste, which gravitated toward scenes of an idealized Christian and Anglo-Saxon past, prevalent in the United States before the Civil War. See Francesca Consagra, “The ‘Ever Growing Elm’: The Formation of Elias Lyman Magoon’s Collection of British Drawings 1854–1860,” in Landscapes of Retrospection: The Magoon Collection of British Drawings and Prints, 1739–1860, exhibition catalogue, Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Poughkeepsie, 1999, 91–92.

14 The text below the drawing reads: “But let my favours hide thy mangled face,/Adieu! And take thy praise with thee to heaven,/Thy ignominy sleep with thee in the grave/ –Prince of Wales (Henry IV, Part I).” After the first line, the following has been skipped: “And, even in thy behalf, I’ll thank myself/For doing these fair rites of tenderness.” On the verso are additional pencil sketches by Trumbull.

15 The Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776, 1786–1820, oil on canvas,

20 7/8 x 31 in., Trumbull Collection, Yale University Art Gallery, 1832.3.

16 John Trumbull, Autobiography, reminiscences and letters of John Trumbull, from 1756 to 1841 (New York: Wiley and Putnam, 1841), 147.

17 See The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker’s Hill, 17 June, 1775, 1786, oil on canvas, 24 5/8 x 37 in., Trumbull Collection, Yale University Art Gallery, 1832.2.

18 William H. Gerdts and Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr., “A man of genius”:

The Art of Washington Allston, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1980, 54; 154–157. Allston was also a teacher of Vassar charter trustee Samuel F.B. Morse (1791–1872).

19 Allston’s work represents Act II, scene 2, when Titania says, “Come, now a roundel and a fairy song;/Then, for the third part of a minute, hence;/

Some to kill cankers in the musk-rose buds, Some war with rere-mice for their leathern wings,/To make my small elves coats, and some keep back/The clamorous owl that nightly hoots and wonders/At our quaint spirits. Sing me now asleep;/Then to your offices and let me rest.”

20 See Nathalia Wright, ed., The Correspondence of Washington Allston (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1993), 404, n. 5; 415, n. 2.

21 This work was particularly well known thanks to its reproduction in

John and Seth W. Cheney, Outlines and Sketches by Washington Allston (Boston: Stephen H. Perkins, 1850).

22 See Thomas W. Leavitt, “The Disposition of the Washington

Allston Trust,” Art Quarterly 19, no. 4, (Winter 1956): 416.

23 Falstaff was also exhibited in 1856. See Theodore Bolton, “Charles

Loring Elliott, An Account of his Life and Work,” Art Quarterly 5

(Winter 1942): 80.

24 For Falstaff in painting, see Pressly, Catalogue of Paintings in the Folger, 29–37.

25 Henry T. Tuckerman, Book of the Artists (New York: G. Putnam & son, 1867), 302.

26 Charles Loring Elliott, Portrait of Matthew Vassar, 1861, oil on canvas, 96 x 63 in., Gift of the Board of Trustees, 1861.1.

27 In his albums, Magoon amassed a number of prints of Stratford. See accession numbers 1864.2.1626–.1631. See also Julia Thomas, Shakespeare’s Shrine: The Bard’s Birthplace and the Invention of Stratford-upon-Avon (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012), 3.

28 “I walked slowly and silently up the aisle in watchful expectation, until in the further corner, next to the chancel, I came to the well-known bust. The clerk quietly rolled aside some matting on the floor below it, and on the worn stone that covers the sacred dust I read those lines which will forever protect that dust and that stone from being distressed, ‘Good Friend, for Jesus’ sake forebeare/ To dig the dust enclosed here./Blessed be the man that spares these stones,/And cursed be he that moves my bones.’” Sanford Robinson Gifford, European Letters, Volume I, May 1855–February 1856 (Washington, D.C.: Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution), 50.

29 Gifford, European Letters, 50.

30 Ila Weiss, Poetic Landscape: the Art and Experience of Sanford R. Gifford (Newark: University of Delaware Press; Cranbury, NJ: Associated University Presses, 1987), 203.

31 Matthew Vassar to Elias Magoon, 15 January 1864, Matthew Vassar Letter Book (1860–1868), 80, Archives and Special Collections Library, Vassar College Libraries.

FIGURES

Fig. 10 William Hamilton, English, 1751–1801, Joan of Arc and the Furies, oil on canvas, 31 1/8 x 21 7/8 in., Purchase, Betsy Mudge Wilson, class of 1956, Memorial Fund, 1966.12

Fig. 11 James Northcote, English, 1746–1831, Hamlet and the Ghost of his Father, ca. 1799, pen and brown ink, 5 3/8 x 4 3/4 in., Gift of Matthew Vassar, 1864.1.261

Fig. 12 John Trumbull, American, 1756–1843, The Death of Hotspur, 1786, brown ink and pencil, 9 x 7 1/4 in., Gift of Matthew Vassar, 1864.1.216

Fig. 13 Washington Allston, American, 1779–1843, Titania’s Fairie Court, before 1837, pen and umber ink with wash and traces of graphite on tinted ground on canvas, 48 5/8 x 72 3/4 in., Gift of the Washington Allston Trust, 1955.4.2

Fig. 14 Charles Loring Elliott, American, 1812–1868, Falstaff, 1856, oil on canvas, 12 7/16 x 10 1/4 in., Gift of Matthew Vassar, 1864.1.28

Fig. 15 Sanford Robinson Gifford, American, 1823–1880, The Shrine of

Shakespeare, 1859, oil on canvas, 9 x 15 1/2 in., Gift of Matthew

Vassar, 1864.1.35