Shakespeare at Vassar

“That which is finest and best”: Performing Shakespeare at Vassar

by Denise A. Walen

Professor of Drama

“Vassar,” according to former college president Henry Noble MacCracken, himself a fine thespian, “has always been stagestruck,” and Shakespeare has figured prominently in the theatrical life of the college.2 The Philaletheis Society, founded as a literary and debate society in 1865, began presenting plays as early as 1869 and produced the earliest Shakespeare productions on campus. In the 1870s, the various chapters of Phil began presenting “Hall plays,” which were productions put on in Society Hall, the stage and small auditorium in the Calisthenium and Riding Academy (later renamed Avery Hall and now the Vogelstein Center for Drama and Film).3 The Delta Chapter of Philaletheis presented Twelfth Night in Society Hall in spring of 1872, and despite “deficiencies of scenery and costume” the Vassar Miscellany praised the excellent cast for presenting such a “pleasant” entertainment.4

Records of Shakespeare productions through the early twentieth century are incomplete, although the college supported at least four Shakespeare plays through 1896, including a second production of Twelfth Night during the 1893-94 academic year. Photos of this production indicate that Phil was able to surmount the deficiencies of costume if not scenery, and while rather fanciful and flouncy, the costumes suggest that Vassar women put a great deal of energy into their productions. All the women involved in the performance were members of various chapters of Philaletheis, and several of the leading actors were also members of the Shakespeare Club, a social organization active through the early twentieth century.5

Beginning in 1900, Philaletheis produced one Shakespeare play each year through 1911. These were the comedies As You Like It (twice), A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Taming of the Shrew (twice), Twelfth Night (again), and Much Ado About Nothing, along with the late comic romances A Winter’s Tale and The Tempest. Philaletheis favored Shakespeare’s comedies because, as the president of Phil wrote in the 1907 Vassarion, his comedies were not “vulgar, disagreeably suggestive or insipid,” and therefore were some of the only comedies suitable for performance.6 The 1904 Taming of the Shrew is well documented in photos, some of which show a large audience of Vassar women sitting and standing in the open-air theatre near Sunset Lake, still a popular site for performance. A cast of twenty-four, richly costumed in Victorian ideals of renaissance fashion, demonstrate that Phil must have had a healthy budget. Winifred Smith directed this production of The Taming of the Shrew and also helped in the direction of the 1903 A Midsummer Night’s Dream.7 Smith entered Vassar as a student in 1901, was inspired by faculty in the English Department like Florence Keyes and Laura Wylie, earned a Ph.D. in English from Columbia University, and returned to teach at Vassar in 1911.8 She would be instrumental in founding the Department of Drama.

The notable exception to the comic tendency during the first decade of the twentieth century was a production in 1905-06 of Shakespeare’s tragic Romeo and Juliet, starring Inez Milholland (’09) as Romeo during her first year at Vassar (Figure: 7). Before the 1920s women played all the male roles in Vassar productions, and while cast lists in the Vassarion yearbook provide full names for students playing female roles, they only provide first initial and surname for those playing male parts. Milholland made a dashing Romeo and went on to star in many other productions. She was extremely active both in theatre and sports at Vassar and became an activist, social reformer, and noted suffragette after college.9 The review in the Vassar Miscellany praised her acting, especially her “unrestrained passion” in the scene where Romeo learns of his banishment. The review also praised the interaction between Milholland as Romeo and the Juliet of Emily Ford, who were “especially commended for the development from the playful tenderness” of their first balcony scene “to the tragic sorrow and passion of the second.”10

Unfortunately, Phil did not capitalize on the success of Shakespearean productions at Vassar in the first decade of the twentieth century, and after 1911 they ceased to produce Shakespeare regularly, to the “profound regret” of some alumnae.11 So noticeable was the absence that in 1922 the “English Speech class in dramatic technique” took it upon themselves to present a production of Romeo and Juliet, again in the open-air theatre, in part “because of the recent agitation” at Vassar, “in favor of a Shakespeare play.”12 While the acting left a little to be desired, the school paper concluded that continued productions of Shakespeare would be “quite worth while.”13 English Speech was a new subdivision in the Vassar curriculum. In 1916, Gertrude Buck of the English Department began teaching classes in playwriting and developed the Dramatic Workshop. Both Professor Buck and her colleague Winifred Smith believed strongly that drama did not exist only as literature but must be examined through practical production, and founded the new subdivision. The curriculum consisted of courses in playwriting taught by Buck, Shakespeare and other early modern dramatists taught by Smith, and a course on “the development of European drama” taught by the college’s new President MacCracken.14 Professor Buck died in 1922, but her replacement was the equally progressive and innovative Hallie Flanagan who worked closely with MacCracken and Smith.

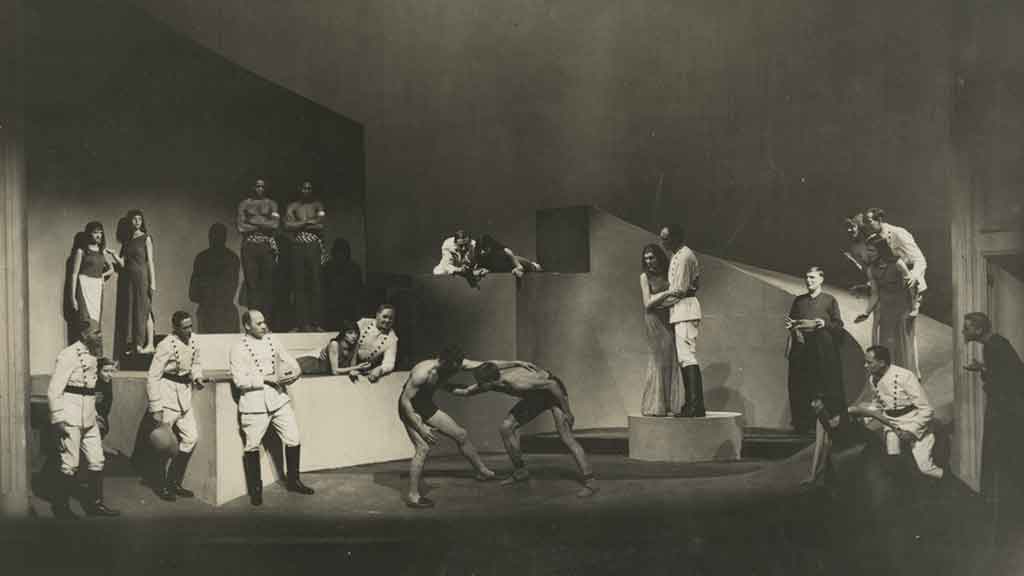

During her time at Vassar, generally 1924-41, Flanagan developed courses in Dramatic Production and founded the Experimental Theatre of Vassar College in the English Department. Unfortunately, she only produced one Shakespeare play while she worked at the college. Thankfully, that production was one of the highlights in her amazing career. Flanagan began thinking critically about Antony and Cleopatra in the spring of 1934, while in North Africa, Greece, and Paris and kept notebook entries about her thoughts on the play and its characters, which eventually found their way into the production.15 Set and light designer Lester Lang created a modular, constructivist inspired set that featured a sweeping curved ramp on stage left to represent Cleopatra’s sultry and sensual Egypt, and a level triangular unit pointing toward the audience stage right to indicate Antony’s severe, militaristic Rome. Vassar Professor of Music, Quincy Porter, composed a score for full orchestra that included an “erotic” Egyptian motif to contrast with “discordant” Roman music.16 On the simple, functional platforms Flanagan staged the many short scenes of the play without interruption, having Lang use lights to indicate shifts in time and place, consciously creating a cinematic effect.17 The exhaustive review of this production by Professor Helen Sandison in the Miscellany News praised the scenery: “The indefiniteness of the scene was its success; we were never at a loss to know where we were when it mattered; and never troubled by a thought of where we were when it didn’t.”18 (Figure:8)

Sandison also praised the acting, finding the Cleopatra of Kalita Humphreys (’35) superior to Jane Cowl’s 1924 New York performance. Professor of Political Science, Gordon Post, who appeared in many Vassar Experimental Theatre productions, played a commanding Antony, “with his splendid figure.”19 And President MacCracken, in the “pivotal role” of Enobarbus, expertly used his “arresting voice” to enliven Shakespeare’s description of “Cleopatra on her barge.”20 In fact, he writes in his memoir, The Hickory Limb, about forgetting that speech one fateful night in performance.21 Sandison concludes her Misc review writing “the community owes a debt to director and cast alike, for planning and carrying through this task which critics have declared impossible and producers have evaded.”22

Records of productions are sparse between the remainder of the 30s through the 50s, which is not surprising given world events at the time. Philaletheis continued to include Shakespeare in its extra-curricular theatrical offerings. In the late 40s through the mid 50s they produced Twelfth Night, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, As You like It, and The Tempest.23 The 1951 “Third Hall” Phil production of Twelfth Night included an all-female cast, which was still typical of student plays. This production is notable in that Frances Sternhagen, who would go on to a prolific and award-winning career on stage and in film and television, starred as Viola.24 Vassar also continued to produce Shakespeare as part of the curriculum, but not through the English department. After multiple proposals by Flanagan and Smith, Vassar founded a Drama Department in 1938, while Flanagan was in Washington directing the Federal Theatre Project, and appointed Winifred Smith as chair. The department’s first Shakespeare offering was a production of The Tempest in 1944 with President MacCracken as Prospero and Professor Post as Caliban.25 The department followed this with productions of A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1950), Much Ado About Nothing (1955) and The Winter’s Tale (1957). The last was an ambitious production with “fifty-seven actors,” including male faculty from the Drama, English, Political Science, and History departments, and fourteen men from IBM.26 The sound scape included sixty-five sound cues of both live and recorded renaissance music, and the production incorporated a number of songs called for in the script.27 The design elements of set and costumes were inspired by Botticelli paintings and Italian neo-classical art.28 By all accounts, the production was “a performance of superb technical achievement,” “beautifully mounted,” “a wondrous and fragile Shakespearean fantasy that moved majestically, airily across the Avery stage.”29

Between the 60s and the 80s the Vassar Drama Department produced few Shakespeare plays, but began to expand the repertoire of Shakespearean selections.30 They offered Pericles on the occasion of the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s birth in 1964, a Pippin-inspired and “thoroughly entertaining” production of All’s Well That Ends Well in 1974, and Cymbeline in 1981 in the “stylized and colorful manner of the Peking Opera.”31 However, since the 90s, productions of Shakespeare have proliferated. Again, Vassar added new plays to its list of productions. One of these was Macbeth, directed by Norse (Beowulf) Boritt, now a Tony-award winning set designer, in 1993. In fact, the tragedies and histories have begun to appear on Vassar stages with some regularity, including productions of Hamlet (the last play on the old Avery stage) and Othello in 2000, and an all-female (now the exception rather than the rule for casting) Henry IV in 2001. Surprisingly, the Drama Department devoted the entire 2000-2001 season entirely to Shakespeare in an experiment at bringing more focus and unity to production work, but there really can be too much of a good thing. Over the past sixteen years, the Experimental Theatre of Vassar College has typically offered a Shakespeare production, or a Shakespeare inspired production, every two or three years.

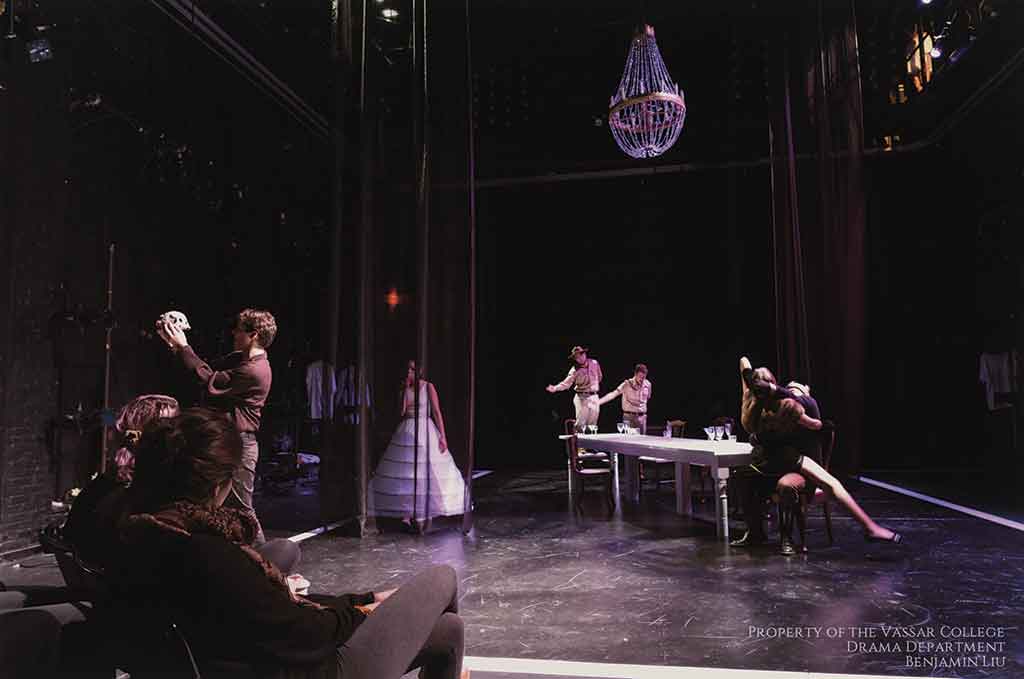

Adaptations of Shakespeare are not a purely contemporary phenomenon. In 1887-88 Philaletheis presented Katherine and Petruchio, a popular revision of The Taming of the Shrew written by David Garrick in 1754. The “fair and fiery” Miss Walworth played Katherine and the “dark and dashing” Miss Ward played Petruchio in a highly praised production.32 The Experimental Theatre has also produced Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1974), Dogg’s Hamlet, and Cahoot’s Macbeth (1986), along with Paula Vogel’s Desdemona: A Play About a Handkerchief (1999). In 2000 the department produced Ophelia, an original play written by Professor James Steerman. In 2003, for the dedication of the new Vogelstein Center for Drama and Film, the department produced an original student-written and composed music drama titled Hamlet Symphony, with text taken from Hamlet, Macbeth, and Romeo and Juliet. Another fascinating Shakespeare-inspired play was The Rose of Youth, a fictional backstage examination of Hallie Flanagan’s 1934 production of Antony and Cleopatra.33 A recent senior project in the Drama Department, titled Here Lies the Water / Here Stands the Man, focused on the role of Ophelia and cultural representations of female “madness” and the situation of women more generally. The script, devised by the ensemble, made use of over thirty source texts ranging from Handel’s “Lascia ch’io pianga,” to Sonny Bono’s “Bang Bang (My Baby Shot Me Down),” with Hamlet, King Lear, and Othello all providing inspiration. This completely student-driven project offered a beautiful deconstruction of Hamlet and the literary construction of female characters.

Since 1999, campus productions of Shakespeare have been supplemented by performances from a professional troupe known as the Actors From the London Stage (AFTLS). Co-founded by actor Patrick Stewart, AFTLS is “one of the oldest established touring Shakespeare theater companies in the world.”34 The group brings classically trained British actors for one-week residencies to US colleges and universities. With residencies organized by members of the English and Drama Department here at Vassar, the company spends a full week offering workshops in classes that include a wide range of disciplines across the campus. They conclude their week with three performances, and have offered The Merchant of Venice, As You Like It, Much Ado About Nothing, Twelfth Night, The Winter’s Tale, The Tempest, and Macbeth to enthusiastic audiences. This too is not a contemporary phenomenon. The great Broadway director Margaret Webster brought her company to campus twice, in 1948 and 1950. On both occasions they presented two Shakespeare plays, first Hamlet and Macbeth and then Julius Caesar and The Taming of the Shrew.35 After a successful career on Broadway, Webster “decided to make her dream of bringing ‘live’ theatre to audiences in small communities, colleges, and schools across the country a reality.”36 That dream proved difficult at times, for example, at Vassar the company found Avery’s lack of wing and shop space and electrical current inadequate on their first visit and performed in the Students’ Building for their second.37

Student productions have continued to include Shakespeare, with Philaletheis offering sometimes challenging plays. In 2009, Phil mounted a production of Titus Andronicus, one of Shakespeare’s earliest, bloodiest, and less frequently performed plays. Presented in the Shiva on an empty white set, the company used paint to represent the various bloody acts of death and dismemberment, so that by the end the performance smeared the white stage with color. The production also used “race- and gender-blind” casting and costumed all characters in uniform, non-gender specific clothes.38 Other student theatre groups have also offered Shakespeare plays. Unbound, founded as a political theatre group, presented Twelfth Night in 2005 to bring “many gender identity issues to the forefront.”39 “Some of the main characters” in this production were “presented as trans-gendered rather than simply cross-dressed” in order to explore “gender-related issues” in the play.40 As the twenty-first century began, two student groups have made Shakespeare their primary focus. One is Shakespeare Troupe, created in 1999 they audition students into the group each year and work as an ensemble. The Troupe’s first production was Macbeth performed on the lawn by Blodgett.41 Since then, Troupe has presented one Shakespeare play each spring in an outdoor space somewhere on campus. These have ranged from a whimsical, 50s inspired A Midsummer Night’s Dream in the orchard, to a chillingly intense and beautifully lit Richard III in the space between the Old Laundry building and the Computer Center. In the spring of 2015, Troupe presented an Appalachian influenced King Lear on the farm, and this spring they offered a brilliantly comic Winter’s Tale, again in the orchard. Merely Players is the second new theatre group performing Shakespeare on campus. Founded in 2009, they presented Measure for Measure as their inaugural production.42 Players present one to two productions a year, including other early modern and ancient dramatists along with Shakespeare. They see their mission as educational, both for the audience and the cast and crew. The group also writes its own plays on occasion, offering a play they titled Merely [Bitches] [?] that focused on Juliet, Rosalind, and Lady Macbeth and explored how literary characters that transgress traditional female gender roles are presented and perceived.43 Over the summer months since 1985, the Powerhouse Theater Training Program, an apprentice program for aspiring actors, directors, and writers, has offered one or two Shakespeare plays outside on the Vassar grounds. These free performances have included a Wonderlandesque As You Like It on the Blodgett lawn, a lovely Twelfth Night in the outdoor amphitheater, and even the harshly political Coriolanus.

Shakespeare has enjoyed a long and vibrant history of production at Vassar. Often challenging social, artistic, or political perspectives and assumptions, the productions always strive for creative integrity and innovation. They have attracted a wide segment of the Vassar community. In recent years, especially with two student theatre groups dedicated specifically to Shakespeare, the number of productions has exploded. Student audiences are flocking to these performances, proving that even 400 years after his death Shakespeare still has relevance in our community.

NOTES

1 Ruth Mary Weeks, “Points of View: Giving Up the Shakespeare Play,” Vassar Miscellany (January 1912), 223.

2 Henry Noble MacCracken, The Hickory Limb (NY: Scribner, 1950), 77-8.

3 “Philaletheis,” Vassar Encyclopedia, https://vcencyclopedia.vassar.edu, accessed 19 April 2016.

4 “Home Matters,” Vassar Miscellany 1.2 (1 July 1872), 60.

5 Vassarion (1894), 44, 91.

6 Mary Borden, “The College Dramatic Society,” Vassarion, Vol. 19

(1907), 106.

7 Vassarion, Vol. 17 (1905), 116 and Vassarion, Vol. 16 (1904), 112.

8 “Winifred Smith,” Vassar Encyclopedia, https://vcencyclopedia.vassar.edu, accessed 21 April 2016.

9 “Inez Milholland,” Vassar Encyclopedia, https://vcencyclopedia.vassar.edu, accessed 20 April 2016.

10 “College News: Philalethean Society,” The Vassar Miscellany

(1 June 1906), 527-8.

11 Weeks, “Giving up the Shakespeare Play,” 221-3.

12 “Romeo and Juliet Presented,” The Vassar Miscellany News (1 June 1922), 1.

13 “Romeo and Juliet Presented,” 4.

14 Evert Sprinchorn, “Stagestruck in Academe,” Vassar Quarterly 87.2

(Spring 1991), 22.

15 Hallie Flanagan, Dynamo (NY: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1943), 70-80.

16 Flanagan, 75.

17 Flanagan, 74.

18 Helen Sandison, “Kalita Humphreys and Mr. Post Star in Antony and Cleopatra; Successful Production Praised,” The Vassar Miscellany News

(19 December 1934), 3.

19 Sandison, 3

20 Sandison, 3.

21 MacCracken, 79-80. See also Flanagan, 75.

22 Sandison, 3. See also, “Experimental Theatre Stages Antony and Cleopatra in Technically Simple Production Following Original Version,” The Vassar Miscellany News (15 December 1934), 1 and 6.

23 Judy Ashe and Ellen Marx, “Past of Experimental Theatre and Phil Shows Rich and Creative Achievements,” The Vassar Miscellany News (18 November 1953), 1 and “Phil Produces “Tempest” In Outdoor Theatre (25 May 1955), 1.

24 “V.C. Third Hall Promises A Starlit “Twelfth Night,” Vassar Chronicle (26 May 1951), 1 and 7.

25 See Winifred Smith, “The Tempest at Vassar,” Vassar Alumnae Magazine (15 March 1944), 22; “Stump Experts, Win Not Encyclopedias But Tempest Seats,” Vassar Miscellany News (27 January 1944), 1; “Tempest Fugit Is Pass Word Of Hard Working DP Group,” The Vassar Chronicle, (10 March 1944), 3; Elizabeth Anne Packard, “’Tempest’ Grows as Tonight’s Opening Approaches,” The Vassar Chronicle (17 March 1944), 1.

26 “Experimental Group Plays Shakespeare,” Vassar Miscellany News (11 December 1957)), 1. The program only lists forty-four actors.

27 Carla Poletti, “Sound Report,” The Winter’s Tale, Box 37, Series 8, Drama Department Production Material, Special Collections, Vassar College, and sheet music.

28 Liz Smith, “Theatre to Set Winter’s Tale With Botticelli Inspired Scenes,” Vassar Chronicle (7 December 1957), 1 and 6.

29 Tessie Dolan, “Theatre Group Achieves Technically Perfect Play,” Vassar Miscellany News (18 December 1957), 2; Dorothy Serlin, “Review of ‘The Winter’s Tale,’” The Vassar Chronicle (14 December 1957), 2; and Elizabeth Klosty, “Vassar Sponsor Variety of Lectures, Dramatic Productions During College Year,” Vassar Miscellany News, Freshman Issue (Summer 1958), 1. See also, William R. Rothwell, “Year’s Work in the Experimental Theatre,” Vassar Alumnae Magazine (October 1958), 14.

30 Records for student productions during this time are sparse.

31 “Weekend Production: Memorial to Bard,” Vassar Miscellany News (4 March 1964), 1; Julie Sisk, “’All’s Well That Ends Well’ Begins Just As Well,” Miscellany News, (10 May 1974), 7; and Jens Krummel, “Shakespeare Oriental Style,” Miscellany News (20 November 1981), 8.

32 “Home Matters,” Vassar Miscellany (1 February 1888), 203-4.

33 Sarah Rebell, “Dynamo Theatre Lab a morphing drama project,” Miscellany News (21 February 2008), 15 and Sarah Rebell, “Dynamo keeps actors, audience intrigued,” Miscellany News (10 April 2008), 17.

34 “History,” Actors From the London Stage, Shakespeare at Notre Dame, http://shakespeare.nd.edu/actors-from-the-london-stage/history, accessed 3 May 2016.

35 “Webster Company Plays Shakespeare, Vassar Chronicle (4 December 1948), 1; “Webster Production of Hamlet, Macbeth Arrives Next Week,” Vassar Miscellany News (8 December 1948), 1;

36 “Noted Dramatic Troupe Offers Two Shakespeare Productions,” Vassar Chronicle (22 April 1950), 1 and 4.

37 Barbara Lechtman, “Lechtman Interviews Margaret Webster; Hears Experiences of Traveling Company,” Vassar Miscellany News (3 May 1950), 3 and “Margaret Webster’s Players to Perform at V.C. Tomorrow,” Vassar Miscellany News (26 April 1950), 1.

38 Wally Fisher, “Bloody Bard of Avon play bashes conventions,” The Miscellany News (16 April 2009), 13.

39 Andy Berger, “Unbound uses the Bard to explore gender,” The Miscellany News (1 April 2005), 15

40 Berger, 15.

41 Joanna Johnson, “Troupe will work under Improv,” The Miscellany News (3 December 1999), 3 and 6.

42 Thea Ballard, “Rebranded Shakespeare group to debut with new ‘Measure for Measure rendition,” The Miscellany News (10 December 2009), 15

43 Adam Buchsbaum, “Devised play explores Shakespearean female archetypes,” The Miscellany News (19 April 2012), 15.