How Accurately Do We Judge Others’ Intentions?Not at All, According to New Research

How Accurately Do We Judge Others’ Intentions?Not at All, According to New Research

It’s almost impossible to guess people’s intentions simply by observing their behavior. That’s the conclusion reached by a research team at Manchester University in England. And the youngest member of the team, Vassar senior Andrew Willett, played a key role in the breakthrough study, published in January by a prestigious scholarly journal.

Willett, a Cognitive Science and German double major from Durham, NC, was the lead author of a paper published in Attention, Perception and Psychophysics, an internationally recognized, peer-reviewed psychological journal. The paper was entitled, “Control Blindness: Why people can make incorrect inferences about the intention of others.” News of the research was carried in several mainstream British publications, including The Daily Mail and Medical Daily.

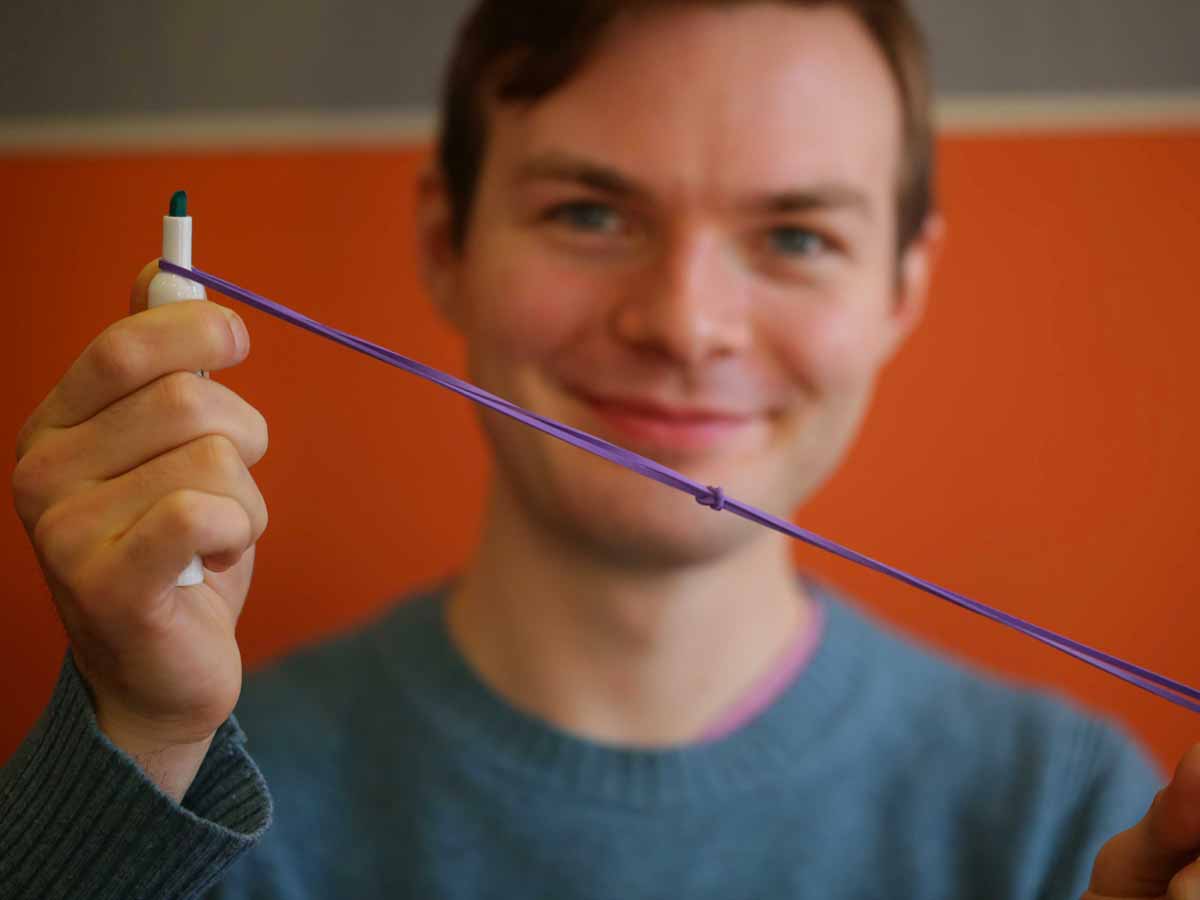

The Manchester research team was able to fool more than 350 people into thinking a person they observed in a video controlling the location of a knot in a rubber band was doing something completely different. The study showed that people routinely misunderstand others’ motives when they observe their actions.

In the experiment, one person controlling the rubber band was told to try to keep the knot above a dot on a piece of paper. The other person was told to try to move the knot away from the dot. But no one who observed this exercise came close to guessing what was going on. “One of our test subjects said he thought the people in the video were drawing a map of Crete,” Willett says. “Another said they were drawing a picture of two kangaroos boxing.”

How did a Vassar undergrad end up working on a project with a renowned clinical psychologist, Dr. Warren Mansell, at a university thousands of miles from Poughkeepsie? The story begins three years ago when Willett enrolled in an introductory cognitive science class taught by Prof. Gwen Broude.

Willett says he was captivated by Broude’s teaching methods (“She gives students the freedom to test their own ideas,” he says) and by a branch of psychology called Perceptual Control Theory. “Gwen spent one class in Cognitive Science 100 talking about this theory, and it fascinated me,” he says. “I did some more reading and I saw that Dr. Mansell and other people at Manchester University were doing a lot of work in the field.”

During his sophomore year at Vassar, rather than simply continuing to read about what Dr. Mansell was doing, Willett sent him an email: “I asked him if maybe I could come over in the summer and work for him.”

Mansell, who says he’s never met an undergraduate quite like Willett, agreed, and the research began in May 2015. Over the next few months, Willett, Mansell and other researchers found hundreds of volunteers to participate in the experiment and analyzed the data.

Mansell, an internationally recognized expert in Perception Control Theory, says Willett had earned the lead authorship of the paper that was published. “Andrew has no parallel among undergraduates in terms of his grasp of science, his work ethic, his optimism and initiative,” he says. “He strives for perfection with an openness to regular constructive feedback and a wholly inquisitive mind. This enabled him to contribute to the execution, data management, analysis, presentation and write-up of the study, which would not have been completed without his constant involvement.”

Broude says she too was impressed by Willett’s dedication in pursuing his interest in Perceptual Control Theory. “I’ve seen a handful of students over the years who develop an interest in some idea and pursue it across their time at Vassar,” she says. “In my experience, Andrew was very unusual in this regard. He had a deep interest in PCT, pursued it via literature and relationships and worked out for himself the meaning, implications, applications, contributions and limitations of the field. “

Broude adds she was also impressed by Willett’s sophistication in his assessment of the theory. “He did not become a sycophant, which surprised me as it is very common to be unwilling to acknowledge that a theory in which you are invested isn’t perfect.”

Willett says he’s indebted to both Mansell and Broude for encouraging him to pursue his work. “I’m grateful to Dr. Mansell for naming me first author on the paper although he played a big role in designing the study and doing the background literature research,” he says. “I’m hoping that my experience will inspire others to be more open to collaborations like this. Perhaps my experience could help other promising students from a variety of backgrounds get their foot in the door.”

Willett says he thoroughly enjoyed his project with Mansell and plans to continue that work in the future. But he’s not certain what academic path he will ultimately pursue. He is a semi-finalist for a Fulbright Fellowship that would enable him to teach English to secondary school students in Germany next year. And this summer, he plans to shadow some physicians, hoping the experience will help him decide whether to apply to medical school.

Willett says his time at Vassar had led him to be open to a variety of ideas and career paths. “Vassar taught me to look at things holistically and to explore alternative methods of doing things,” he says. “There’s no one way to look at the world.”