In a letter dated April 20, 1866, Annie Glidden, Vassar Class of 1869, wrote to her brother John, “They are getting up various clubs, now, for out-door exercise. They have a floral society, boat-clubs, and base-ball-clubs. I belong to one of the latter, and enjoy it, hugely, I can assure you.”

As this is one of the first known mentions of women playing baseball, it has been quoted widely by sports scholars, but until recently, we didn’t know much else about Annie Glidden—who she was, where she came from, or how her life unfolded after she graduated. Annie’s story and the stories of many of the other early graduates are coming to light thanks to the efforts of Vassar historian Colton Johnson, Professor Emeritus of English and Dean of the College Emeritus, his student researchers, and geneaologist D.B. Brown, Dean of Students Emeritus.

“We’ve been working on this for three years,” says Johnson. “I started the project with an academic intern, Geneva Toland, who graduated a couple of years ago, and have since been working on it with Heather Kettlewell ’18. Our intention was to look at the 353 women who were admitted as students at Vassar when it opened in September 1865. We’ve since narrowed the field a bit to focus on the 63 who actually took the bachelor’s degree, and they’ve turned out to be a fascinating bunch of people.”

According to John Raymond, the President of Vassar College when it opened in 1865, more than 1,000 potential students had shown interest in the college prior to the opening. “How many of them actually presented themselves that September, we’ll never know, and we’ll never know exactly how they were examined,” says Johnson, “but we do know that by the 23rd of September, they had winnowed the pool down to the 353 that would be students that first year.

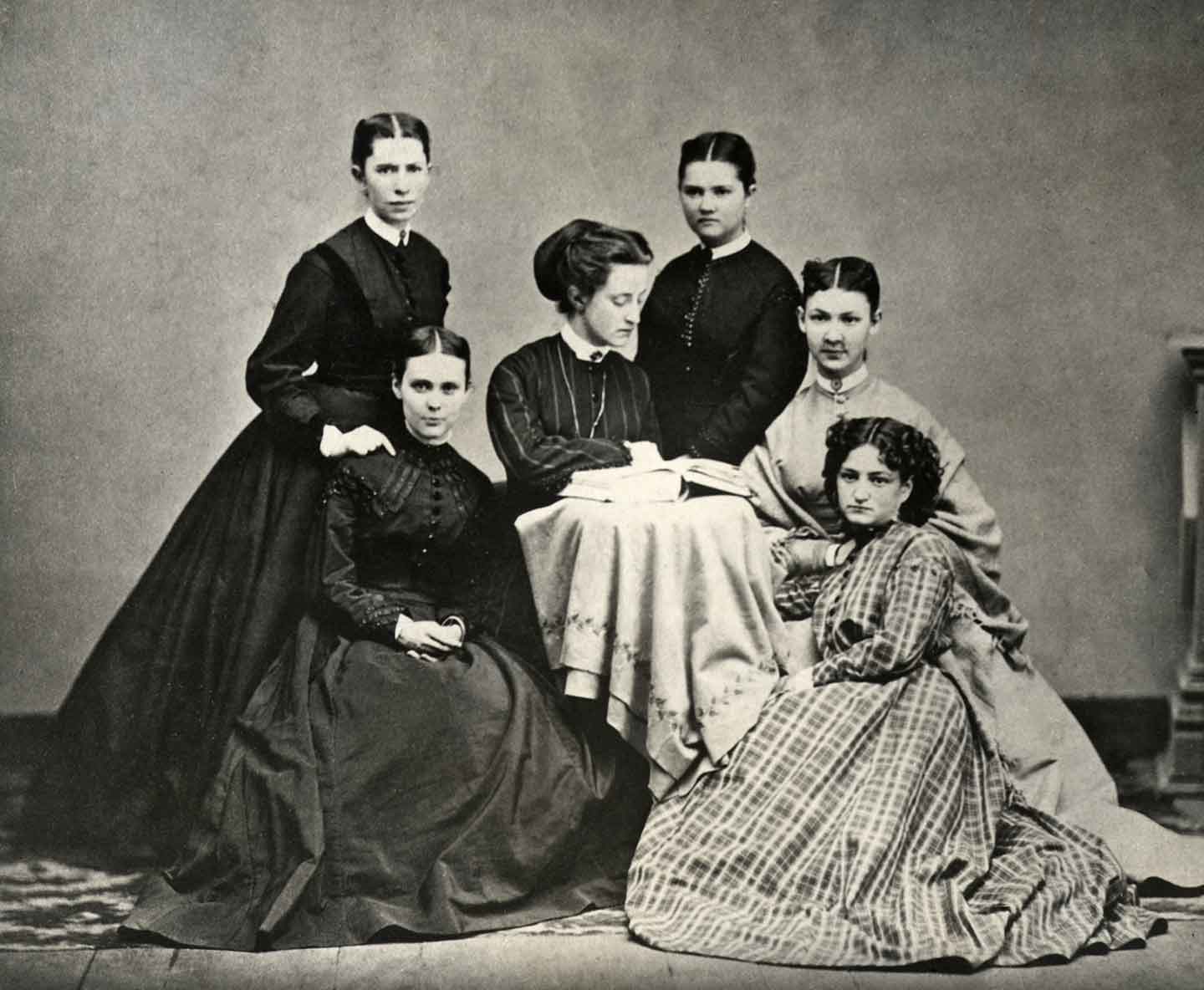

Pictured here are three of the four members of Vassar’s first graduating class, 1867, leading the alumnae parade in 1915 to celebrate the college’s 50th anniversary. On the left is Maria Dickinson McGraw from Detroit, MI (1843 –1920). Dickinson married fellow Detroiter Thomas McGraw soon after graduation, and became a mother, housewife, and lifelong champion of the college. On the right is Helen D. Woodward from Plattsburgh, NY (1843-1941). Woodward returned to Plattsburgh after graduation and became a teacher and principal of the high school there. In the middle is Harriette Warner Bishop, also from Detroit, MI (1845 –1944), who moved to Missouri after graduation and married William Bishop. When her husband died in 1878, she returned to Detroit with their three children and eventually became the principal of Detroit Central High, where she remained until 1914. At age 95, Bishop attended the college’s 75th anniversary and received a standing ovation as she entered the Chapel.

Those first entrants were predominantly from the Northeast, but a surprising number came from quite a distance--two from San Francisco, California, ten Southerners, and a sizeable contingent of Midwesterners, 20 states represented all told. There were also seven Canadians and one woman from the “Hawaiian Islands.” “Hawaii wasn’t even an American protectorate, let alone a state, in those days,” says Johnson. “She went home in February. Anyone who’s lived through February in Poughkeepsie can probably see why someone from Hawaii would go home.”

Many were accompanied to Poughkeepsie by their parents, but many made the journey on their own. From Martha Warner ’68, we have this account of her arrival from Detroit, Michigan, with her sister Harriette:

On the morning of September 20, 1865, two girls, travelworn and weary, stepped from the Albany train to the platform of the Poughkeepsie station, and looked hesitatingly about them. But there was no hesitation on the part of the Poughkeepsie officials ; —with a decision born of conviction, those girls were hurried into a crowded omnibus, and before they had had time to faintly gasp, “Vassar College,” they found themselves forming part of a procession stretching in broken lines from the railway station to the college entrance. One of them writes: “We drove up in an omnibus full of girls with their fathers and mothers. I wished I were anywhere else in the world. I never dreaded anything so much as I did getting there. We came in sight of the building, and it looked just like the pictures. We drove through the lodge up to the door and alighted; then we looked to see what other people did, and, as they all posted up to the front door, we posted after them.”

Contrary to the prevalent notion of Vassar’s elitist origins, these early students were typically not from the upperclass but from the rising middle class. “The upperclasses were still sending their daughters to Europe to be trained up,” says Johnson. “It was the increasingly affluent and able middle class who were probably more inclined toward this kind of experiment.” Sarah Glazier’s father, for example, sold groceries in Hartford, CT, and then rapidly expanded his business to include a wholesale operation and some other businesses. Annie Glidden’s father is listed in the 1860 census as a manufacturer. Mary Reybold’s father started out as a farmer in Delaware and eventually became the president of a steamship company.

“These are people who were a lot like Matthew Vassar,” says D.B. Brown. “They tend to be people who have built their own fortunes rather than inherited them. They tend to be Protestant. They are all white. They’re only a couple of generations removed from the Revolution. Almost all the ones I’ve looked at have ancestors who fought in the Revolution. Many had ancestors who arrived on the Mayflower or shortly thereafter.”

And many of them died young. “Childbirth was often the cause,” says Brown. “Also illnesses and accidents were more likely to be fatal in those days because of the lack of medical knowledge.” Mary Reybold, class of 1868, for example, was one of the six students known as “the hexagon” who studied with Maria Mitchell for all three years of their Vassar careers. She later traveled with Mitchell to Iowa in ’69 to observe and record the solar eclipse. After graduation, Reybold returned home to Delaware City, married a physician, Dr. Stiles Kennedy, in 1872 and bore three children. A few days after the birth of her last child, on March 22, 1878, Mary Reybold Kennedy died, undoubtedly of complications from childbirth. She was the fifth member of the class of ’68, which numbered 25, to die within a decade of graduation.

Another member of the hexagon, Sarah Louise Blatchley ’68, to whom we owe the symbolic interpretation of the college colors, rose and grey, died in 1873 after a prolonged illness described by her classmate Sarah Glazier as “a severe congestion of the lungs, resulting in a cough”—probably tuberculosis. She became ill in 1870, but in her letters to Glazier over the next few years described herself as becoming stronger. She wrote to Glazier from Savannah in 1871, then from Florida in the spring of ’72 , and from a steamer in the Atlantic Ocean in October of that same year en route to San Diego, California, where she finally succumbed. Why these long journeys so far from her family in Connecticut? “We don’t know,” says Brown, “but there’s always a reason. Medical treatment, maybe? A relationship?”

As with most kinds of research, genealogical research tends to open up at least as many questions as it answers. “All of these questions are open ended,” says Brown. “You go down the rabbit hole, and you don’t know what you’re going to find. But what happens is that these people become real. At least that’s what we’re hoping. These were real women who led interesting lives and made tough choices and whose families had their own dramas. And sometimes their stories are really sad.”

So what do we know about Annie Glidden of baseball fame?

She was born and grew up in and around Portsmouth, Ohio. By the time she arrived at Vassar in 1865, she was an orphan. Her mother died when she was ten, her father when she was 15. They left her and her two brothers, John and Carlos, well off. Her father’s real estate holdings are listed in the 1860 census as worth $230,000—over six million in today’s dollars.

We have quite a few of her letters—mostly to her brother John, to whom she was quite close—in the Vassar College Digital Library. The letters give a wonderful sense of what life at Vassar was like—drama productions, baseball (of course), Founder’s Day, lectures and laboratories, sermons that moved her, her classmates, their illnesses, the views from Main, the weather, and the difficulties of travel to and from the college. She writes about staying at Vassar over the winter holidays along with some of the other girls because the journey to Ohio was too difficult during the winter months.

Annie was the president and valedictorian of her class. Though not named by the “Occasional Correspondent” to the New York Times, it was undoubtedly Annie described in this paragraph in the lengthy article about that year’s commencement activities: “The valedictory completed the day, and was delivered by the President of the Philalethean, her topic being ‘Culture a Means, not an End.’ She urged that mere intellectual adornment be not accepted as a desideratum of an educational system, but rather that symmetry of character which must grow out of the grand possibilities of a recognized individuality. She closed with an eloquent appeal to her class to ever honor their Alma Mater.” (New York Times, June 27, 1869, “Vassar College. A Woman’s Impressions.”)

After graduation, she returned home to Portsmouth for a time before going to medical school in Ann Arbor (we don’t know whether she ever actually practiced medicine) and then marrying Frank Houts, a lawyer, of Warrensburg, Missouri, in July of 1874. 1875 finds them living in Milwaukee where their first two children were born—Elizabeth in 1875 and Catherine in ’77.

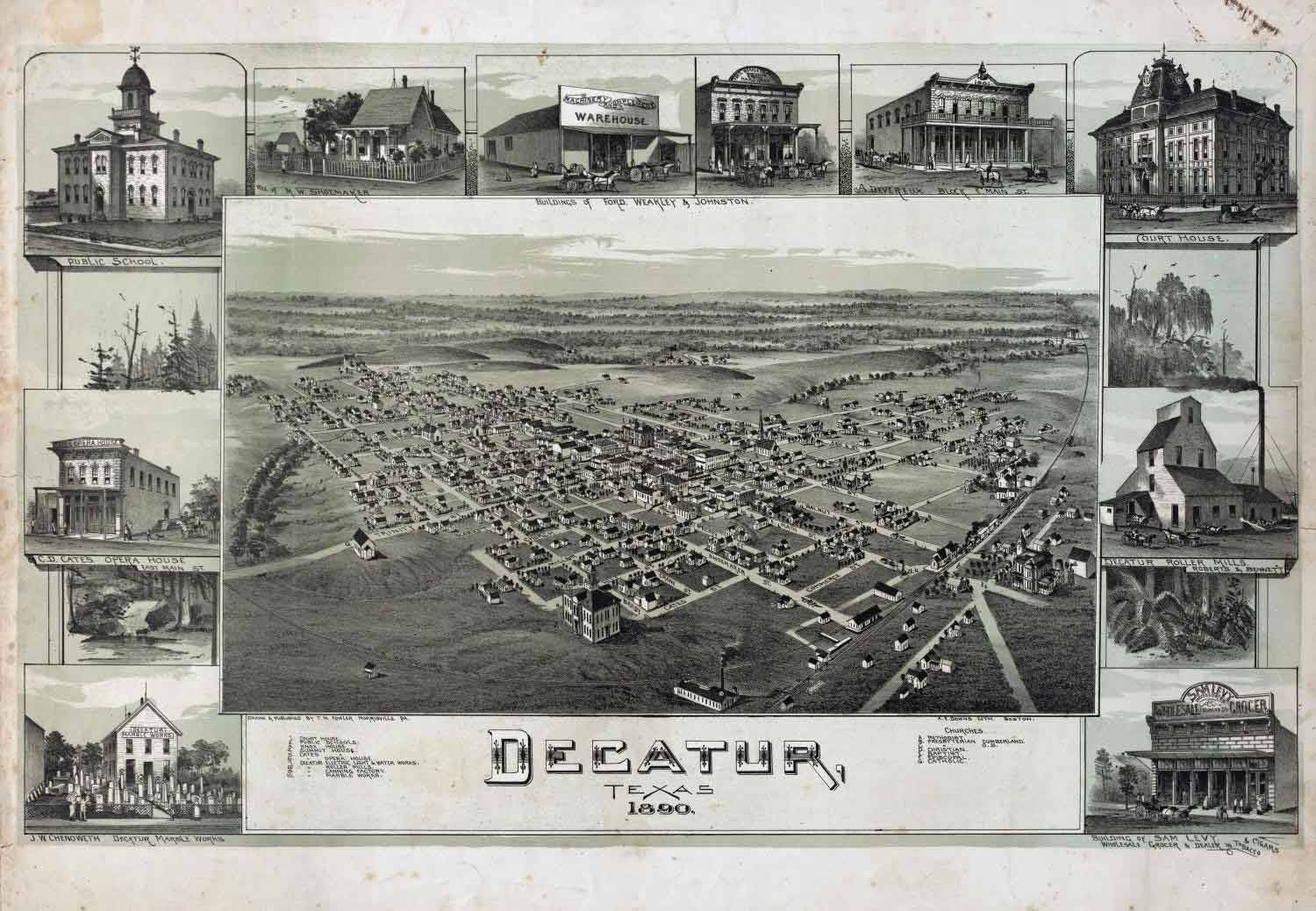

And it’s at this point that things get particularly interesting. We know from an account published over 50 years later by Bev Bunce, Elizabeth’s son and Annie’s grandson, that Frank Houts moved the family to Decatur, Texas, to take up ranching. “Forsaking the legal profession for a turn at Texas ranching, he was one of the first three men to import Hereford cattle into that state to replace the wild longhorn, and he is credited with being the first man to stretch a barbed-wire fence in Texas.”

In 1882, Houts made a cattle drive from Texas to Kansas on the Chisholm trail. Annie, three daughters, and their English governess, Miss Allison, made the trip with him—and Annie kept a diary of the trip, generously excerpted in Bunce’s article. She describes the food, the cowboys, encounters with Native Americans, crossing flooded rivers, and storms. “The tent blew over on us, and we had to lie on the wet ground, and all the hands were riding herd and singing to prevent a stampede. When daylight finally came, the cook saw our plight and let us up to dry around his fire. Never has a hot breakfast tasted so good.”

The next news we have of Annie comes under this tragic headline six years after the cattle drive: “SUICIDED. Sad Death of Mrs. Annie Glidden Houts. Mournful Ending of a Pure and Beautiful Life.” This unusually detailed obituary describes Annie’s “bad health, which at times affected her mind.” According to the article, she had twice previously attempted suicide and had been sent to Chicago for treatment. When she returned, she “seemed in better health than ever….For two or three days she was in good spirits but grew despondent on the departure of her husband for this city [Fort Worth] on business. On the morning of her death Mrs. Houts was very affectionate to her three little girls, who at half-past seven o’clock went down stairs to play. About eight o’clock one of the little ones wanted her mother, and hunted through the house for her. She finally looked in a closet and found her mother hanging to a rafter, the body turning round and round.”

What led to such a tragic end? According to the obituary, “Mrs. Houts was a great social favorite, and her home was said to be one of the happiest in the State.” It’s unlikely that we will ever have a definitive answer, but it seems clear that Annie suffered from a mental illness, and such conditions are even now inadequately understood and often stigmatized. Ironically, in a letter to her brother (January 17, 1869), she wrote of a mutual acquaintance, “I am sure I hope Kate is recovering her mental powers, for there can be nothing worse it seems to me than the loss of one’s mind.”

Like so many of her Vassar classmates, Annie Glidden earned the epithet “pioneer”—fully equal to the challenges of a rigorous education, eager to push the envelope of social conventions, willing to pull up stakes and leave family and friends behind for a life on the frontier—but she was also a creature, and a victim, of her time and place, as are we all.

If you wish to delve further into the lives of Vassar’s earliest students, you will find many more profiles in the Vassar Encyclopedia, but be advised: their stories are addictive. As Colton Johnson said when asked why he’s devoted so much time to this project, “You’ve just gotta love ’em!”

An exhibition about the early graduates titled The First Students will be on view in the James Palmer III Gallery from Friday, September 22, through October 5, 2017.