The world is waking up to the contributions of Grace Murray Hopper ’28, computer pioneer, Navy Rear Admiral, and former Vassar Assistant Professor. It’s about time…

On the 11th floor of a building in lower Manhattan, 10 pairs of computer coders sit typing at monitors. They’re three days into the Grace Hopper Program at Fullstack Academy, a software engineering boot camp for women and people who identify as female. The program, which launched in January 2016, is so successful that it only charges tuition for participants once they secure jobs. No one has gotten a freebie yet.

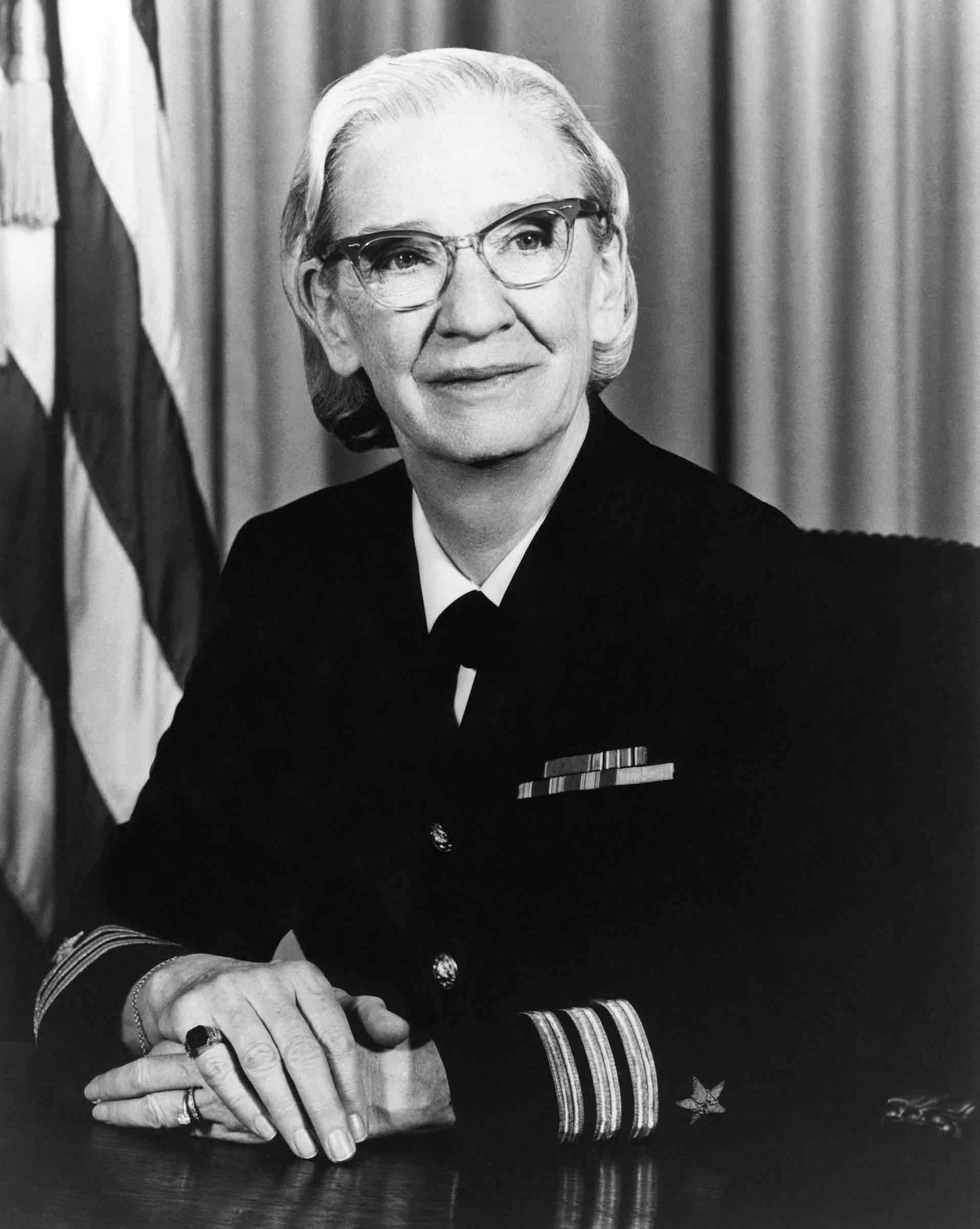

Hopper, the program’s namesake, has been called the “queen of code” and “mother of computing.” The 1928 Vassar alumna and former faculty member was one of the world’s first computer programmers, working as part of a Navy effort on Howard Aiken’s Mark 1 calculating machine during World War II. She later became one of the few women to earn the rank of rear admiral, and when she retired in 1986, she was one of the longest-serving officers in Navy history and the oldest-serving officer in the United States Armed Forces. She died in 1992 at 85.

Hopper’s contributions have gained renewed attention in recent years. In November 2016, President Barack Obama said in his State of the Union address, “That spirit of discovery is in our DNA. America is Thomas Edison and the Wright brothers and George Washington Carver. America is Grace Hopper.” That November, he awarded her a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor. And in February, after people demanded that Yale remove John C. Calhoun, the 19th-century statesman who promoted slavery, from the name of a residential college, the university announced it would rename the building after Hopper, effective July 1.

“I don’t think I know anybody who’s a woman in tech who doesn’t know about Grace Hopper,” says Sarah Zinger ’10, a web engineer who volunteered as mentor at the Grace Hopper Program. “She’s definitely one of the role models that people look toward.”

Code Maker

Born in 1906, Hopper grew up in New York City and enrolled at Vassar at 17. She studied math and physics, but her interests were diverse. She graduated Phi Beta Kappa and Vassar granted her a fellowship to attend Yale.

In 1931, while studying at Yale, she returned to Vassar to teach math. Her first courses were Elementary Structural Drawing, Integral Calculus, and Shades, Shadows, and Perspective. She later became an assistant professor. In notes to the Quarterly, she was described as both a “great teacher,” and a “sharp wit at the luncheon table or in faculty meetings.”

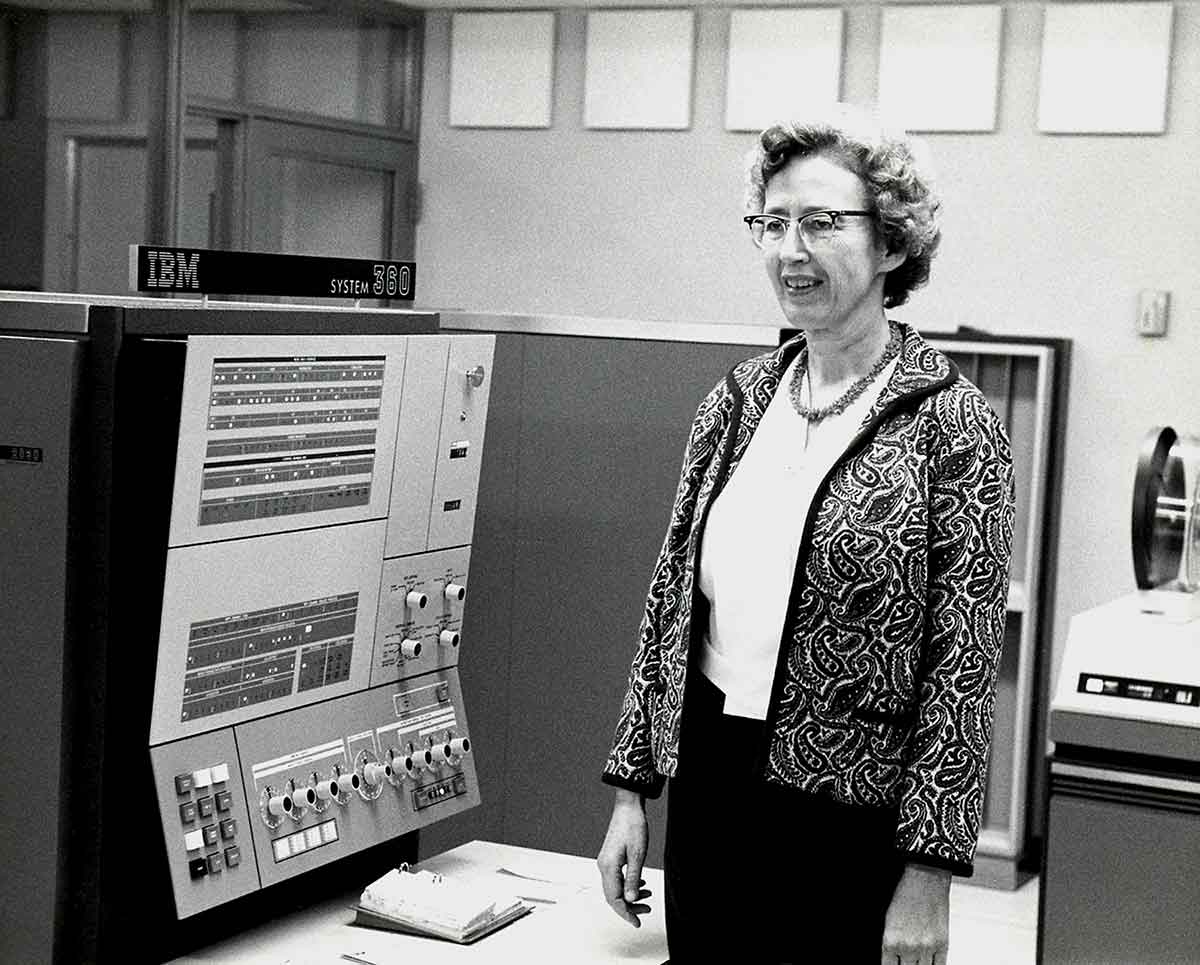

After the U.S. entered WWII, Hopper convinced Vassar to grant her leave so that she could enlist in the U.S. Navy Reserve. After training, she went to Harvard to work on one of the world’s first computers, running calculations to help in the war effort. The machine was 8 feet tall, 51 feet long, and contained 750,000 parts.

After the war, she left active service and resigned from Vassar. (She would return to campus at least 9 or 10 times to speak.) But she continued working in computing. In 1952, she invented a compiler that translated English into computer code, paving the way for the creation of programming languages Fortran (Formula Translator) and COBOL (Common Business-Oriented Language), and making it possible for generations of non-experts to do their own programming. For a 1966 Vassar “Class Report,” she wrote, “I will do almost anything to stay with the computers. The field is still critically shorthanded. Of course, I hope the price will come down some day so I can have a computer of my own!” She continued working on projects for the Navy, and in 1983, President Ronald Reagan promoted her to commodore, a rank later renamed rear admiral. She retired in 1986.

“Waiting for You to Wake Up”

One vestige of Hopper’s years at Vassar is the two-story colonial house she built near Kenyon Hall. Computer science professor Jenny Walter lives across the street. Walter channels the computer pioneer when she takes students each year to the Anita Borg Institute’s Grace Hopper Celebration of Women in Computing.

“It was overwhelming, the amount of women that were there, the amount of incredibly brilliant and talented women,” says Laura Barreto ’17, who has attended three times. The conference inspired her to apply for a career development workshop for minority students, which helped her land a job after graduation—at Microsoft.

Vassar’s computer science program might not have existed without Hopper. “She’s sort of like the grandmother of the department,” says professor Nancy Ide, who established the department in the early 1990s. That’s because one of Hopper’s students, Winifred Asprey ’38, went on to teach at Vassar and decided that the school needed a computer.

In 1956, Asprey ran the idea by Hopper: “What do you think about Vassar getting into computers?” Her former professor responded: “I’ve been waiting for you to wake up.” Around a decade later, Vassar opened its computer center, and Hopper spoke at the ceremony. She told attendees that the world was only starting to know what to do with computers, and that if the power of the machines scared anyone, people could “always pull the plug.”

Those advancing Hopper’s legacy say it’s important to recognize her accomplishments, given that, as of 2015, women comprised just 25 percent of the country’s professional computing workforce, according to the National Center for Women and Information Technology. In 2014, women earned just 15 percent of computer science bachelor’s degrees. The figures for certain groups of women of color were also disproportionately low.

Fortunately at Vassar, there are now nearly six times as many computer science majors as there were a decade ago—117 this past school year. Ide says her classes are growing more diverse. All of those students likely know about Hopper, since the department has installed two displays about her in Sanders Physics. One of them, a banner hanging in the stairwell, depicts Hopper alongside one of her famous sayings: “The most dangerous phrase in the language is, ‘We’ve always done it this way.’”