In the late ’70s when Eric Beringause ’80 was a student at Vassar, he applied for a summer job as a seasonal interpretive ranger with the National Park Service at Canyon de Chelly (pronounced CAN-yon deh SHAY) National Monument in northern Arizona. “And much to my surprise, I got the job,” he says.

It was the perfect job for an anthropology major. “Canyon de Chelly is probably one of the most spectacular places on the planet,” says Beringause, “and it is unique in that it’s entirely within the Navajo Tribal Trust of the Navajo Nation and is one of the few National Park Service units that’s cooperatively managed.”

The canyon is the site of some magnificent Anasazi Indian ruins and also home to a small community of Navajo, or Diné, as they call themselves. “So on the archaeological side and on the cultural anthropology side, for me it was just a fascinating place.”

The experience, he says, was transformative. “Here I was—this kid from New York. I had no car or anything, so I ended up hitchhiking a good part of the way there. And all the folks I met out there, the folks in the tribe—boy, they couldn’t have been nicer.”

That first summer, the National Park Service staff of about 10 consisted entirely of Anglos. Beringause became friends with a local Navajo guide named Wilson Hunter and convinced him to apply for a seasonal ranger job the next summer. Hunter got the job and eventually made the National Park Service his career. Today he is the Deputy Superintendent at Canyon de Chelly, and he and Beringause have stayed in touch throughout the years.

Fast-forward 30 years or so. Beringause is now the CEO of Gehl Foods, the largest manufacturer in the world of nacho cheese sauce and one of the largest specialty manufacturers of nutritional beverages, located in Milwaukee. “About six years ago, Wilson called me up and said, ‘We’ve got this program called the Student Conservation Association, and we need funds.’”

A few years earlier, Hunter had reached out to the Student Conservation Association to explore the possibility of sponsoring a native SCA high school crew in the canyon. “The SCA had never had anything like that,” Hunter recalls. “These would all be Native American kids from the Canyon de Chelly area, but there would be some differences between our crew and the usual SCA crews. Our kids are very close to their families, so we thought maybe they could go home on weekends to be with their families. We decided that the program would have an educational component—environmental and cultural. We wanted to educate them about why they were doing what they were doing. So we talked about bringing speakers in to talk to them on these subjects. And they would need money to cover their expenses, for clothes and books and whatever they need for school, so we decided to give them a $1,000 stipend.”

The first year, they squeezed money out of the park budget to pay for the program. “And it was very successful—the first Native American SCA crew,” says Hunter. “Now, there are many, all the way to Alaska, but we were the first ones.” But federal budget cuts put the program in jeopardy, and Hunter began to look for donors to keep it going.

When Hunter first brought the program to his attention, Beringause had never heard of the Student Conservation Association (SCA) or its founder, Vassar alumna Elizabeth Titus Putnam ’55, whom he finally met in Seattle a couple of years ago at an SCA event. But he agreed to support the program and over the years has played an increasingly active role in securing funding.

On a tip from Natasha Brown, Associate Vice President for Development and Principal Gifts, Beringause contacted Michael Prior ’86, who also has an interesting connection with the Navajo Nation. Prior is the CEO of ATN International (ATNI), a company that specializes in telecommunications investments in remote, underserved areas.

“The Navajo Tribal Utility Authority (NTUA) contacted us back in 2009 because they wanted to work with us to build out their fiber network and to support a wireless network,” says Prior. “At that point, they had only one wire line provider and one wireless provider, and much of the reservation didn’t have any service.”

ATNI already had a wireless operations network around the Navajo Nation which they folded into the new deal with the NTUA, giving the business a positive cash flow from day one, and they structured the deal so that the NTUA eventually became the owners of the business, with ATNI providing management services. “This is pretty rare,” says Prior. “Essentially we were able to help them take part in standing up a new business that they now own, adding employees, adding stores, providing new services, providing competition. Now about 98% of the employees are Navajo, and lots of good things happened as part of the project.”

The first year Beringause reached out to Prior, he was in a quandary—he had less than two weeks to pull together the funds so they could hire the students. “In the kind of business we’re in, you need to find ways to connect to your community, which includes charitable giving,” says Prior. “Normally we like a little time to do our ‘due diligence,’ but because of the Vassar connection, I said okay. We’ll promise you this year and do our due diligence after the fact.”

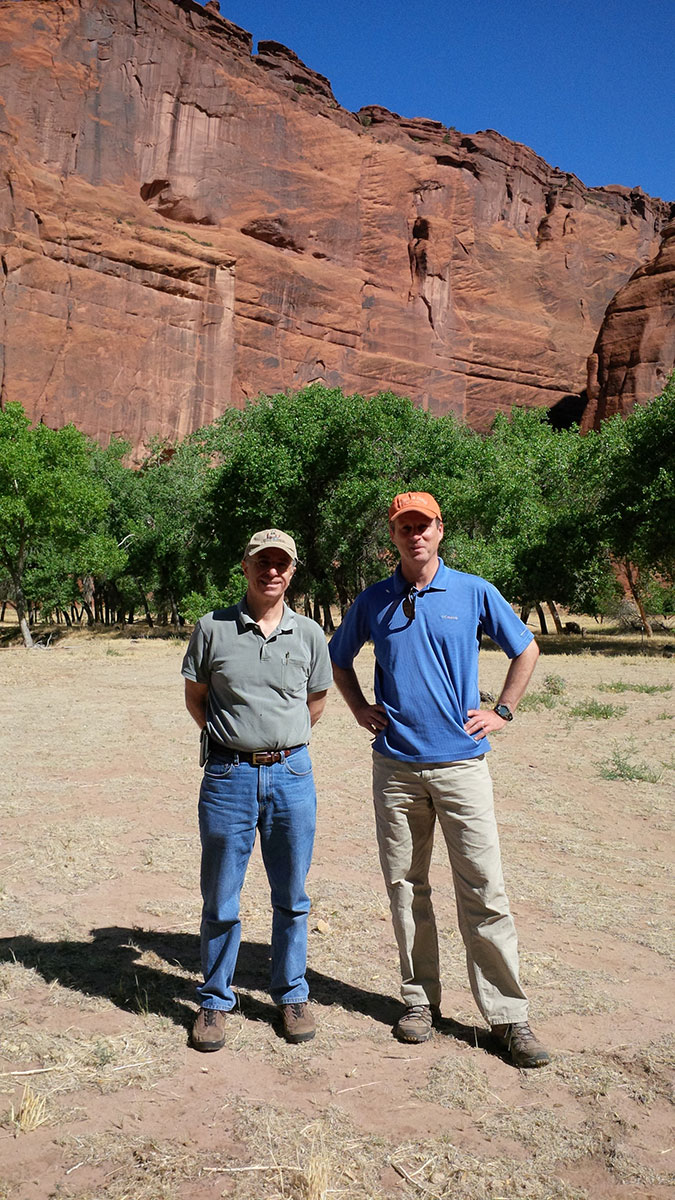

Last year, Prior and Beringause visited the canyon together while the program was in operation. Liz Putnam had planned to go as well but had to cancel at the last minute. “It was nice to see,” says Prior. “There’s just nothing like seeing those high school students doing that job. They were a special group of kids.”

Hunter, who plans to retire soon, is a little concerned about the future of the program. “We’ve just had some great kids, and a great variety of kids,” he says. “Every year we have a potluck with the families. This is a time when the families and the kids come together, and of course they share their experiences with their families. They talk about how it changed their lives, and what they want to do in life now, and what they want to do for the environment, and what they want to do for their homeland. These are the things they talk about.”

Beringause is hopeful that some sort of endowment can be created to put the program on a more stable footing. “Eric has really become involved in this program,” says Hunter. “He brings the donors out here to see the crew. He enjoys it. I think he enjoys it so much that he wants other people to experience it, too.”

“It’s just a different world,” says Beringause. “This is my way of paying back a little bit for the great time I had there and the kindness they all showed me.”