The Commencement of Vassar’s “First Collegiate” ClassJune 24, 1868

The Commencement of Vassar’s “First Collegiate” ClassJune 24, 1868

In Vassar’s first year, 1865-1866, no attempt was made to place the 116 women among of the 353 students who were classified as “Regular Collegiates” in ordered class years. When the classification was done, in the spring of 1867, four graduating seniors were recognized, and Maria L. Dickinson, Elizabeth L. Geiger, Harriette Warner, and Helen D. Woodward became the first Vassar graduates, the Class of 1867.

The graduating Class of 1868—Vassar's “first collegiate year,” President Raymond said in 1873—included 19 of the first students and six who had entered the college a year or two later. The 25 women were the Class of 1868, the sesquicentennial of whose commencement we observe in 2018.

Mary Lavinia Avery (1848-1904)

New York City, New York

Mary Lavinia Avery ’68 was born in South Glastonbury, Connecticut, on February 6, 1848, the daughter of Alfred Avery and Lavinia Dexter Avery. Her father was a partner in Avery, Cecil & Butler, a wholesale dry goods firm, and Mary attended private schools in Orange, New Jersey, and New York City and took private lessons from her brother-in-law, Professor Allen S. Hutchens of the Wayland Academy, a Baptist men’s school in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin.

In 1867, Mary was one of the editors of the first student journal, The Transcript. The class historian in her senior year, she spoke on “Isolation” as one of eight student orators at their Commencement in1868. She returned to Vassar in 1873 to serve as a “critic” for the junior composition classes of Professor of English Truman Backus. She left this position in 1878, to aid her father, who had fallen ill in Whitewater, Wisconsin. In 1887 she joined the editorial staff in New York City of the Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia, then in its first year of preparation. With over 500,000 entries, the dictionary was one of the largest encyclopedic efforts in the English language. Avery’s work focused on the definition of literary works and their illustration by quotations ranging from Middle English to the present time. Avery was one of three women recognized in his preface by the work’s editor when its first edition appeared serially between 1889 and 1891.

Avery’s work as a lexicographer led to several literary friendships, including that with the American poet, critic and editor James Russell Lowell. In their half-personal, half-professional correspondence Avery suggested revisions to Lowell’s work and Lowell, according to a contemporary biographer, always wrote her name “out full length” because it was “so ‘liquidly musical’ that it runs in his memory ‘like a brook.’” In 1892, Mary Avery became a lecturer in literature at the School of Library Training of the Pratt Institute where she taught English composition, gave lectures on English and other literatures to the School of Library Training and edited the Pratt Institute Monthly. She also wrote occasional pieces at this time for the New York Evening Post.

In 1898, Avery left the Pratt Institute to join the staff of the New York Public Library as classifier and cataloguer of its music collection. Stricken subsequently by a ineradicable illness she stayed for two years in the General Memorial Hospital in New York and later removed to a private hospital in the city, from which she maintained a spirited correspondence with her Vassar acquaintances up until her death on January 25, 1904.

After the death of Mary Avery, a tablet was placed in her honor in the Vassar Chapel. The Pratt School of Library Training established a memorial book-case, a hundred books of which she was most fond, with an inscription from “The Marriage of Cupid and Psyche” by Charles Sayle: “Here is a book made after mine own heart. Good print, good tale, good picture and good sense. Good learning and good labor of old days.”

Anna Louise Baker (1847-1941)

Norwalk, Ohio

Descended from Connecticut military figures in both the French and Indian and the Revolutionary Wars. Anna Louise Baker ’68 was born on December 19, 1847, in Norwalk, Ohio, the only daughter in the five children of Daniel Albert Baker, a banker and farmer, and his wife Belle Benson Baker. Her father and his brother, George Griswold Baker—later, Abraham Lincoln’s counsel in Italy and Greece—were pioneer settlers in the “Fire Lands” of the Connecticut Western Reserve, coming to Ohio in the winter of 1829 from Norwich, Connecticut, on a sleigh. Daniel Baker’s young daughter was remembered by local historian C. P. Wickham in The Firelands Pioneer (1918): “As a girl she was very attractive and agreeable.”

After graduating from Vassar in the Class of 1868, “Annie” Baker married James Franklin Brooks, on June 5, 1873. A Civil War veteran and the son and heir of a wealthy physician, James Brooks was a merchant who, moving his family to California, became a successful realtor. Annie and James lived first in San Diego and, later, in Sacramento, where they had five children. Her husband died in 1916 and Anna Louise Baker Brooks died in Sacramento on July 16, 1941.

Unable to attend her 65th class reunion in 1933, Annie Baker Brooks sent a sad reminiscence of her Class Day in 1868. Charged with planting the class tree, she and “Bella” Carter ’68 had interrupted a trustee meeting in the Library to borrow the spade used by Matthew Vassar to break ground for the college. Giving them the spade himself, Mr. Vassar “with a few words wished us success and returned to his desk.” Returning the spade later that day, the young women learned that Mr. Vassar had died while reading his farewell address. “Without doubt,” she recalled, “we two girls were the last students to converse with our honored Founder. We went through with our Class Day and Commencement ceremonies, but with a devastating sense of bereavement and loss.”

Elizabeth Reynolds Beckwith (1845-1929)

Stanford, Dutchess County, New York

The eldest of the nine children of George Washington Beckwith and Abigail Thompson Beckwith, Elizabeth Reynolds Beckwith ’68 was born January 16, 1845, on a farm acquired after the Revolutionary War by her great-grandfather, Sylvanus Gilbert Beckwith, near Stissing Mountain in Dutchess County, New York. Her father, a prosperous farmer and dairyman, served as chairman of the board of the Stissing public school that she attended and where she taught for four years before coming to Vassar in 1865.

One of seven graduates selected to present essays at Commencement on June 24, 1868, Elizabeth Beckwith spoke on “Epochs.” After graduating, she continued her education with summer classes in Latin and Greek at the nascent Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. She taught briefly in the high school in Freeport, Illinois, before returning to the East to teach from 1874 to 1877 in a public school in New York City. In June of 1877, she joined the Normal College of the City of New York—after 1914, Hunter College—as a tutor in Latin and Greek, remaining there until 1908, when a crippling illness forced her to retire to the family home in Dutchess County, where she lived with a sister and a brother and where she died, on January 18, 1929, at the age of 84.

Elizabeth Beckwith returned frequently to Vassar, joining eight of her classmates in their third reunion in 1885 and several of them again at Commencements in 1890, 1897 and 1911.

Sarah Louise Blatcheley (1844-1873)

New Haven, Connecticut

The daughter of Samuel Loper Blatchley and Mary Ann Robinson Blatchley, Sarah Louise Blatchley ’68 was born June 6, 1844, in Madison, Connecticut. Her father was active in the mercantile, insurance and real estate businesses. “Louise” was educated in the public school of North Madison, Connecticut and subsequently in New Haven, where she completed the year-long classical preparatory course at Yale. A member of the self-defined “Hexagon”—the five 1865 students, along with Helen Storke ’68 who had come to Vassar in 1866, who had taken Maria Mitchell’s astronomy courses throughout their college years—she was described by another of the six, Sarah Mariva Glazier, as “a true poet.” “While we plodders were painfully evolving a knowledge of ‘micrometer measurements,’ ‘collimation errors,’ and all the prose of instrumental astronomy,” Glazier recalled, “she delighted in ‘sweeping for comets,’ and from those lonely vigils. . . would gather fancies, which, woven into the web of her deeper thought, would produce a fabric whose wondrous sheen called attention to its strength as well as its beauty.”

At Vassar Louise studied broadly, from Greek and Spanish to astronomy and physiology. About her physiology class, taught by the college physician, Dr. Alida Avery, she told a friend, “You would like Miss Avery in class, and the dry bones and manikins would delight your heart. I am getting quite philosophical; it would take considerable to make my blood run cold now.” Elected president in her senior year of Vassar’s first student organization, the Philalethean Society, she was 1868’s class poet and its valedictorian. Louise returned to Vassar for Commencement in 1869 to speak on “Individuality.” That summer she traveled to Iowa with Miss Mitchell’s group to observe and report on the solar eclipse of 1869 for the American Ephemeris and Nautical Almanac, the country’s official astronomical publication. During this period she was also studying German and Sanskrit.

In the winter of 1870, Sarah Louise Blatchley grew ill with lung congestion from which she failed ever to recover. Travelling to Florida and going by steamer to California, she wrote to a friend, in February 1873, “I am really an invalid in earnest.” She died in San Diego on March 13, 1873, at the age of 28.

A poem written by Louise and published in 1867 in The Transcript, is both the origin and the definition of Vassar’s college colors, rose and silver-gray. “With true college zeal,” her classmate Sarah Glazier recalled, recognizing Louise’s “deeper thought,” “we had decided that we must have ‘colors,’ and finally fixed upon ‘Rose and Silver-gray’ for no reason except as a pretty combination. But we readily accepted her interpretation as it appeared shortly after in the ‘Transcript’:

Our morning dawneth on the hills,

A great and glorious day;

We take our colors from the East,

The Rose and Silver-gray.

The twilight with its dimming stars

Transfigured by his ray,

Brightens before the rising sun

To Rose and Silver-Gray.

The old, the darkened skies of night,

Our night, are passed away,

And ‘gainst their gloomy background gleam

The Rose and Silver-gray.

So, fair dawns morning on the hills

And bright shall be the day;

We take our colors from the East.

The Rose and Silver-gray.

Julia Electa Bush (1844-1928)

Turin, New York

Julia Electa Bush '68 was born March 6, 1844, in Turin, New York, the daughter of Horace C. Bush and Alma Abigail Mott Bush. The family moved west, living in Evansville, Wisconsin, until the death of her father in 1856, after which her mother brought her to Lyons Falls, New York. She attended school in Utica, New York, prior to entering Vassar in September of 1865.

Graduating in 1868, Julia Bush taught Latin in private schools in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania, and New York City for many years. On June 7, 1894, she became the second wife of Clinton L. Merriam, a New York businessman, banker and former Republican Congressman (1871-75), whose wife, the former Caroline Hart, had died the previous year. Married at “Homewood,” Mr. Merriam’s country estate in Locust Grove, New York, the couple spent much of their time in New York City where Mr. Merriam continued his business career. They later made Locust Grove their principal home.

After her husband’s death, on February 18, 1900, Mrs. Merriam lived in Italy for a few years, returning to the United States just before World War I. In 1917 she moved to Watertown, New York, where she lived in the temperate months. She spent her winters in Washington and New York City. On February 19, 1928, at the age of 85, she was struck and instantly killed by a “automobile truck” at the corner of 72nd street and Madison Avenue. Three weeks before she had come to New York City for a reunion of Vassar alumnae and to see “The King’s Henchman,” an opera by Edna St. Vincent Millay ‘17 and the composer Deems Taylor. While in the city, she had lunched with Vassar alumnae at the Biltmore and had tea with old friends at the home of Blanche Ferry Hooker ‘94. “An informal service,” Vassar Quarterly reported the following July, “was held in New York and many of her intimate friends were present. Her body was taken to Lyons Falls, New York, for burial.”

Described in Vassar Quarterly at the time of her death as “a gifted artist...possessed of a brilliant intellect,” Julia Bush Merriam was a painter. She produced original paintings and also meticulous copies of famous works. In her will she left two of her paintings to Vassar, a copy of a Madonna by Bellini and an unframed copy of a Botticelli. The paintings were eventually hung in the tower room of Alumnae House.

Isabella Carter (1849-1925)

Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts

Isabella Carter ’68 was born in Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts, on November 8, 1849, to Eliza Harriet Bayley Carter and Timothy Walker Carter, a Chicopee businessman and banker who served as a representative to the Massachusetts Legislature in 1847 and 1848. He was also a state senator in 1860 and 1861. Before enrolling at Vassar in September 1865, Isabella attended Farmington Academy in Connecticut for a preparatory year, 1864-1865. After graduating—as the class’s “senior spade orator”—and a year as a preceptress at the Ithaca Academy in Ithaca, New York, “Bella” Carter returned to Vassar, earning a master’s degree in art, principally German and Greek, in 1872. That year she married the brother of her classmate, Mary Prentice Rhoades. David Prentice Rhoades was a Cornell graduate and a businessman in the Syracuse, New York, area. An entrepreneur active in several fields, Mr. Rhoades traveled frequently. In 1904, the couple lived for six months in Europe.

The Rhoadeses were active in church and social activities in Syracuse. A founder of the Central New York branch of the American Association of University Women, Bella served as the president of that organization. Her daughter, Mabel Carter Rhoades, earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees at Syracuse University and the PhD at the University of Chicago in 1906. A sociologist, she published widely and taught at Syracuse and at Wells College. Bella’s son, Sumner Rhoades, also a Syracuse graduate and active in the field of insurance, was selected in 1922 as the first secretary of the New York Fire Insurance Rating Organization, a group recently mandated by state law.

David Prentice Rhoades died on July 6, 1919, and, remembered in a Syracuse obituary as “a pioneer in the movement for higher education and the advancement of women,” Isabella Carter Rhoades died on November 18, 1925.

Isabella Carter Rhoades’s interest in the “national flower movement” that arose as the quadricentennial of Columbus’s landing in North America approached was among her many social concerns. Her widely acclaimed poem, “The Columbine for Columbia,” first published in 1893 in the Springfield Republican and set to the tune of “Columbia the Gem of the Ocean,” nominated the columbine. The first of its three stanzas praised the flower’s ubiquity:

Emblazoned in panoply regal,

The rose and the lily may shine;

Aquileza! akin to our eagle,

We claim thee, O wild columbine!

Through commonwealths twice two and twenty

And states yet in embryo, too,

Scatter widely they symbols of plenty,

Cornucopias red, white and blue.

Achsah Mount Ely (1845-1904)

Manalapan, New Jersey

Descended from several of New Jersey’s early families, Achsah Mount Ely '68, one of the four daughters of Joseph Ely and Catharine Conover Ely, was born in Manalapan, New Jersey, on November 10, 1845. Her early schooling was at the Young Ladies’ Seminary in Freehold, New Jersey. The school, founded in 1844 by Amos Richardson, a graduate of Dartmouth College, offered an advanced curriculum. At Vassar, she studied astronomy, mathematics and, apparently, philosophy. She spoke on “The Philosophy of Herbert Spencer” as one of the eight graduates selected to read their work at their Commencement in 1868, and she was among the Vassar students who joined Professor Maria Mitchell in Iowa in 1869 to observe and report on the solar eclipse.

After graduation, Achsah Ely served as lady principal at the Connecticut Literary Institute at Suffield and later at the Peddie Institute in Hightstown, New Jersey, where she remained until 1876, when she took a teaching position at the Normal College of the City of New York. Founded in 1870 as a women’s college for training teachers, the college became Hunter College in 1914. During these years, Ely also did graduate work at Newnham College in Cambridge, England, and at Chicago University, a Baptist college established in 1856, which had admitted women in 1872. In 1887, Ely returned to Vassar as head of the mathematics department.

A member of the American Mathematical Society from its founding in 1891 as the New York Mathematical Society, she was also an active member of the Alumnae Association of Vassar College from its earliest days, serving as chairman of its first committee formed to secure alumnae representation on the board of trustees. From 1885 to 1890, she was chairman of the committee that secured funding for the Alumnae Gymnasium (1889), later named Ely Hall in her honor. On December 13, 1904, Achsah Ely suffered a fatal heart attack while walking on campus.

At Professor Ely’s memorial service in 1905, her colleague and classmate, Professor of Astronomy Mary Watson Whitney ‘68 recalled when “Miss Ely and I came together to this place, to begin our collegiate course. . . . The college was an experiment—it was not wholly a college. Many people did not believe in it at all; some within its own walls doubted if it could pass the experimental stage and result in any essential degree unlike the many seminaries and academies that then represented the finishing stage of a girl’s education. . . . In this small group of college students of that early day there was no other more earnest and eager and hopeful than Miss Ely. She was imbued with ambition for the successful working of the experiment.”

Anna Maria Evans (1848-1906)

McKeesport, Pennsylvania

Anna Maria Evans ‘68 was born on December 12, 1848, in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, to Oliver Evans, a wealthy McKeesport landowner, and Mary Ann Sampson Evans, whose family also had a large farm in the area. Oliver Evans's father and grandfather had owned tracts of land near Wilmington, Delaware. His maternal grandfather, Hugh Alexander, emigrated from Scotland in 1736. A successful farmer, carpenter, and wheelwright in Pennsylvania by the late 1750's and a leader in the Second Continental Congress in 1776, Hugh died in Independence Hall while serving on the newly formed Assembly.

Anna Maria Evans's four brothers, three older and one younger, became lawyers and farmers, and in 1866, Anna Maria came to Vassar. Graduating with the Class of 1868, she returned to the family farm in McKeesport, locally referred to as the "Evans Estate." In 1875, she married John Wesley Bailie, a lawyer who had graduated in 1867 from the University of Pennsylvania. The couple lived on Penny Street in the "Estate," where their nine children were born between 1876 and 1889. Tragically, two of Mary's sons, Robert and Cadwallader, drowned while swimming in the nearby river in 1888. Two of the daughters, Mary Evans and Anna Forbes, later graduated from Vassar, in 1897 and 1908, and three sons, John, Thomas, and Raymond, became Princeton graduates.

In the 1880's, Anna Maria became a well-known temperance advocate in western Pennsylvania, serving as the President of the Allegheny County W.C.T.U. In 1886, she declined reelection, but the organization unanimously reelected her anyway.

The Bailie family continued to live at several addresses on the Evans Estate in McKeesport, John's law offices were in Pittsburgh, and the couple had a secondary residence in that city. Anna Maria had a nervous breakdown in 1900, and she never fully regained her health. She died on March 23, 1906 from complications of heart disease. The Pittsburgh Press described her as "one the wealthiest residents in McKeesport," and in her will she gave bequests to numerous causes, including the Boards of Missions of the Presbyterian Church. He continued his law practice and his work as the Vice President of the First National Bank of McKeesport. John Bailie died in 1910.

After Anna Maria's death, John Bailie donated $1000 to Vassar's department of astronomy for the purchase of a stereocomparator, a device developed in 1901 by the German physicist and pioneer in stereoscopy Carl Pulfrich widely used in topography and astronomy.

Gertrude Frothingham (1845-1921)

Rochester, New York

Born in Caledonia, New York, on November 6, 1845, Gertrude Frothingham '68 was the daughter of Thomas Frothingham, a Union College graduate and an attorney, and Mary Ann Smith Frothingham. The family moved to Rochester when Gertrude was about three. After graduating from Vassar, Gertrude married Arthur Radcliffe Williams, an engineer, on December 24, 1868. The couple had four children, Gertrude Mary, Arthur Radcliffe, William Wells and Frances Wells, the first three of whom were born when the family lived, from 1869 to 1875, in Petroleum Center and Oil City, in Pennsylvania, where Arthur was a superintendent in the oil fields. The household returned to Rochester, where Gertrude was a music teacher, soloist, accompanist and organist. In 1908 she played the processional at Vassar’s 42nd Commencement, in the Vassar Chapel.

Gertrude Frothingham Williams’s husband died in 1884, at the age of 39. In 1911, accepting a position as a music teacher and accompanist, Gertrude moved to New York City. She died February 3, 1921, in Brooklyn, New York, of pneumonia.

Writing to a former Vassar student on January 26, 1867, Gertrude’s classmate, Sarah Glazier, offered a comic glimpse of her as performer and musician, roles she would enjoy in her later years: “Miss Frothingham was the leader,” Glazier wrote, “of a fine orchestra of combs, and with her gray wig, swallow-tailed coat, and white beaver, was quite too much for the gravity of beholders.”

Sarah Mariva Glazier (1846-1919)

Hartford, Connecticut

Sarah Mariva Glazier ‘68 was born in Hartford, Connecticut, on March 7, 1846, the daughter of Phoebe Walker Glazier and Carlos Glazier, a successful wholesale and retail merchant. Graduating from Hartford Public High School in 1863, she was that school’s first female graduate to go to college. At Vassar, she was one of the three editors of The Transcript, the first student journal. One of the many early students inspired at Vassar by Professor Maria Mitchell, she became deeply interested in astronomy. One of the six students in the Class of 1868 who studied in Miss Mitchell’s astronomy classes in each of their Vassar years—the self-defined “Hexagon”—Sarah joined the group of seven Vassar students who journeyed to Iowa with Miss Mitchell in 1869 to observe and report on the solar eclipse. At her Commencement in 1868, her essay, “Force,” had preceded the valedictory of her Hexagon companion, Sarah Louise Blatchley.

After graduation Sarah taught at the Auburndale Female Seminary in Massachusetts in 1868, and at Chelsea High School from 1869 to the fall of 1870, when she moved to Chicago, where, she later told a friend, she had “been trying to bring up about sixty young Chicagoans.” While in Chicago, Glazier studied astronomy with the famous mathematician and director of the Dearborn Observatory, Truman Henry Stafford. She received her master’s degree from Vassar in 1972, and, with the granting to Vassar in 1898 of its first chapter at a women’s college, Sarah Glazier attained membership in Phi Beta Kappa. The Chloe Pierce Professor of Natural Science at the new Buchtel College in Akron, Ohio, in 1873-74, she served as the chair of natural science at Vassar in 1874 and as the first professor of mathematics and astronomy when Wellesley College opened in 1875.

Sarah Glazier married the Reverend John Mallory Bates in Hartford on October 10, 1876. Between 1883 and 1886, the couple lived in Topeka, Kansas, where Rev. Bates was chaplain and headmaster at Bethany College. They subsequently moved to Nebraska and in 1903 settled in Red Cloud, where Rev. Bates was rector of Grace Church. The novelist Willa Cather, who had been raised in Red Cloud, was in his congregation. In Nebraska, Sarah Glazier Bates, continuing to learn, studied political science, European history and constitutional law as a graduate student at the University of Nebraska. She was an active member of the D.A.R, the Association of Collegiate Alumnae, and the Graduate Club of the University of Nebraska.

The couple had three sons and a daughter: Luke Manning, born October 18, 1877; George Whitney, April 13, 1879; Carlos Glazier, October 14, 1885; and Sarah Louise, March 23, 1884—the latter named in memory of her mother’s late, close friend, Sarah Louise Blatchley ‘68. Sarah Mariva Glazier Bates died on October 13, 1919, in Lincoln, Nebraska, and was buried at Spring Grove Cemetery in her native Hartford. One of two clerics cited by Willa Cather as the models for the title character in Death Comes for the Archbishop (1927), John Mallory Bates died on May 25, 1930.

Clara Eaton Glover (1845-1890)

Lawrence, Massachusetts

Born in Waltham, Massachusetts, on June 20, 1845, Clara Eaton Glover ’68 was the daughter of Jesse Glover, Jr. and Martha Bartlett Glover. Her father, a descendant of one of the founding families of Massachusetts, was a machinist by trade. In 1860 he moved his family to Lawrence, Massachusetts, where he had been appointed superintendent of the Pemberton Mill, a textile mill rebuilt after the disastrous collapse in 1860 of the original building, in which some 150 workers had died. Clara attended the public school in Lawrence, founded in 1848, and in 1865, at the age of 20, she enrolled at Vassar. A woman who met her at this time described her as of medium height with gray eyes and curly brown hair—“not beautiful” but possessing a “gentle intelligent depth that attracted the attention of all who met her.”

A member of the group that called themselves the “Hexagon”—the six students in the Class of 1868 who had taken the classes in mathematical astronomy taught by Maria Mitchell in each of their years at Vassar—Clara grew close to Professor Mitchell and her father, who lived with his daughter in the Observatory. After her graduation in 1868, William Mitchell wrote to a young Quaker friend “thou art quite right in supposing that I must miss the graduated astronomical class. It is a more severe experience than I had imagined it would be. Clara Glover and Mary Whitney especially, who had in a manner adopted us as step parents, are a great miss to us.” One of seven students chosen to deliver an address at Commencement, Clara spoke on “Earnest Living.”

Graduating in 1868 as the president of her class, Glover returned to Lawrence, where she taught in the high school until her marriage, the following year, to Edwin Ginn, whom she had met in the summer of 1866 when visiting a friend near Orland, Maine, where his family lived. A graduate of Tufts College in the Class of 1862, Ginn had entered college, as had Clara, at a somewhat advanced age, 21. Self-employed as a schoolbook contractor when they first met, he was beginning his career as an educational publisher. The couple married on September 11, 1869.

Edwin and Clara Ginn lived in Boston for several years, at first within walking distance of the publishing house. In 1890, the family—now including Jessie Bartlett Ginn (born 1872), Maurice Edwin Ginn (1875) and Clara Louise Ginn (1879)—moved to nearby Winchester, Massachusetts. Although heavily occupied with both her family and her husband’s business, Clara Ginn maintained contact both with Vassar—contributing, for example, to the Maria Mitchell Endowment Fund in 1889—and with college friends, informing them of a family trip to Europe the same year.

Clara Glover Ginn died at her home in Winchester on October 17, 1890. She was 45 years old. Edwin Ginn became one of the wealthiest men in Boston and was well known as a publisher, peace advocate and philanthropist. The business he and Clara began in 1868, Ginn & Co., remained a foremost textbook publisher for nearly a century after his death, on January 21, 1914.

Edwin Ginn had suffered in college from deteriorating eyesight, and according to her daughter-in-law Clara Glover Ginn was “very ambitious for her husband and did everything in the world to encourage him to equip himself. . . . Every evening, after they were married, she read aloud to him for as long as five hours at a time. This was the result of her determination that he read only the best literature.”

Mary Beulah Griggs (1848-1870)

Center Rutland, Vermont

Mary Beulah Griggs ‘68 was born in 1848, in Center Rutland, Vermont, an unincorporated village in Rutland County, to Samuel Jones Griggs, a prosperous farmer, and Julia H. Kelley Griggs. Both parents came from long lines of New Englanders. Samuel's family moved to Rutland from Brookline, Massachusetts in 1814, and his grandfather and two of his great grandfathers had fought in the Revolutionary War. Julia's family, the Kelleys, originally from Galway, Ireland, settled on Cape Cod in the mid 1600's, and had been in the village of Danby, near Rutland, since the 1790's.

After graduating, Mary moved back to Rutland, and in April, 1869, she married James Champlin Fernald, a Baptist Minister from Massachusetts who had just accepted appointment to a congregation in Granville, Ohio. Mary and James moved to Granville, but in the summer of 1870, pregnant with their first child, Mary fell ill with consumption. She died at the age of 22.

Rev. Fernald married a friend of Mary’s in 1873, and remained in Ohio until the late 1880s, when he moved to a church in Philadelphia. Ten years later, he moved to Richmond, New York. He later became the editor of a Richmond newspaper.

Mary Griggs had a brother, George Henry Griggs, a farmer like their father. After serving for two years in a Vermont infantry regiment in the Civil War, George moved west to Ohio, Minnesota, and eventually Iowa.

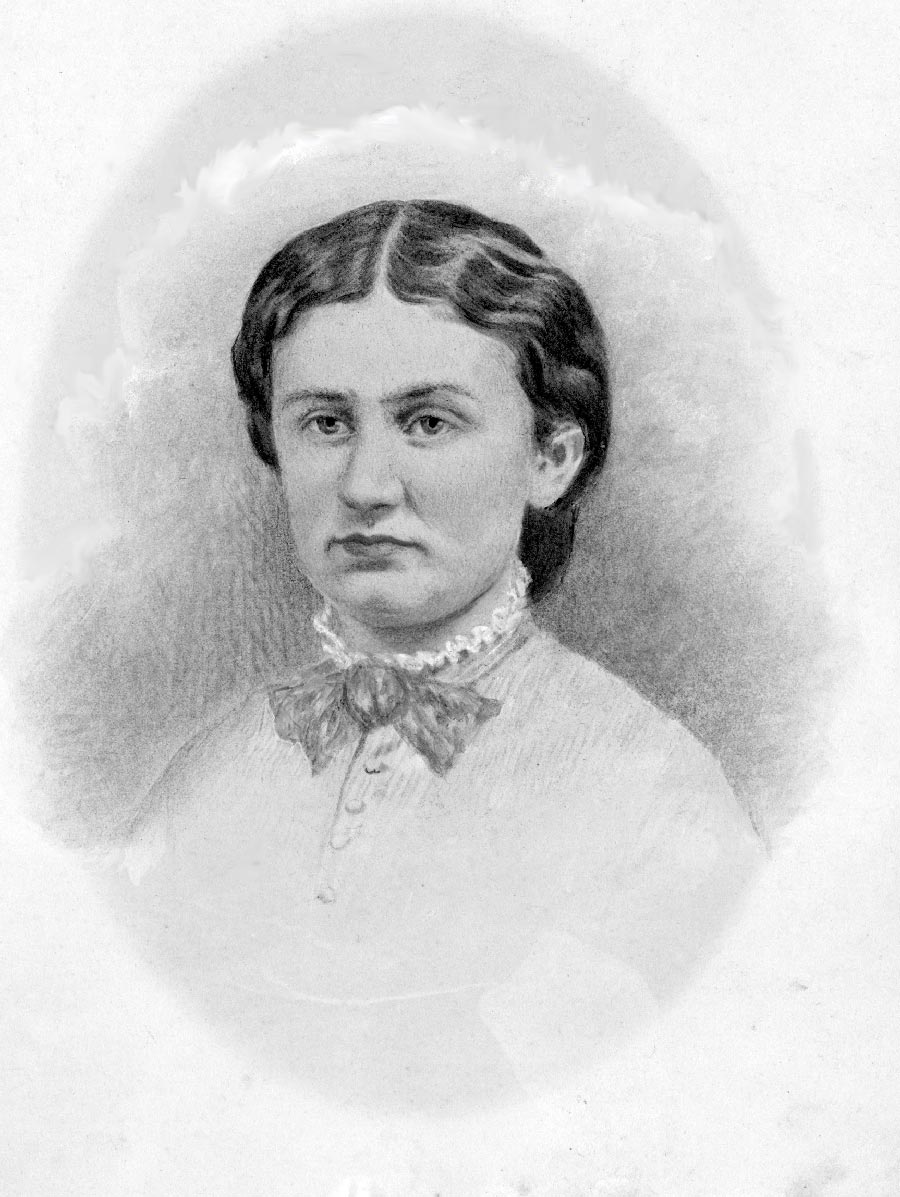

In 1961, George's daughter, Jessie Ruth Griggs Soltow, then 78-years-old and one of the last of the Griggs line, sent a watercolor portrait of Mary Beulah Griggs to Vassar, saying that the college should have this picture of one of its first graduates.

Mary Virginia Higinbotham (1850-1903)

Leavenworth, Kansas

Mary Virginia Higinbotham ‘68 was born, along with her twin brother, Henry Clay, to Alexander Allison Higinbotham and Sarah Burgoyne Higinbotham on January 17, 1850, in Wyoming, a small town in Bath County, Kentucky. In 1856, Alexander Higinbotham and his four brothers moved with their families to Leavenworth, in Kansas Territory, as “Free Soilers,” signifying their opposition to the expansion of slavery. A successful real estate broker and rising community leader by 1864, Alexander represented Leavenworth County at the railroad convention convened in Kansas City, because of the advancing transcontinental railroad, to discuss the future of the Kansas Pacific line.

The following fall, Mary entered Vassar and after graduating with the Class of 1868, she returned to Leavenworth, where, in 1872, she married Lucien Baker, a lawyer who had been elected that year as the city’s attorney. He served as a Kansas State Senator between 1893 and 1895, and was elected to the United States Senate in 1895. Serving one term between 1895 and 1901, he was Chairman of the Senate Committee on Civil Service and Retrenchment.

The couple had three children, Burt, Mary and Charles. Both sons received law degrees, and Mary attended Vassar for two years as a special student in the Class of 1897. In 1901 Lucien retired to private practice, where he was joined by his son Burt, in the firm Baker and Baker. Mary Baker married C. H. T. Lowndes, a U.S. Naval surgeon who eventually retired as a Rear Admiral. The Bakers’ other son, Charles Lowndes, graduated from Georgetown in 1923, received his law degree from Harvard in 1926, and served on the Duke University Law School faculty for many years.

In the last years of her life, Mary Virginia Higinbotham was in very poor health. Between 1888 and 1903, she suffered a series of strokes that left her partially paralyzed. She died in Leavenworth on May 10, 1903, at the age of 53. Lucien Baker died on June 21, 1907.

Of the 353 first students at Vassar, Mary Virginia Higinbotham was one of the two from Kansas. The other student, Mary’s next door neighbor at Fourth and Chestnut Streets in Leavenworth, was Elizabeth Williams ’69, later Elizabeth Williams Champney and the author of the eleven “Three Vassar Girls” novels.

Maria Louisa Hoyt (1847-1891)

Stamford, Connecticut

Maria Louisa Hoyt ‘68, the daughter of Joseph Blachley Hoyt, Jr. and Catherine Krom Hoyt, was born May 6, 1847, in New York City. Among the 353 students first enrolled at Vassar when it opened, she and her younger sister, Frances Anna Hoyt, were among the 63 of those entrants who graduated with bachelor’s degrees, Maria in 1868 and Frances two years later as the president of the Class of 1870.

Maria’s father was a descendant of the original settlers, in the early 1600s, of Stamford, Connecticut, and her maternal ancestors were Dutch settlers in Ulster County in the Hudson Valley of New York State. A prominent tanner and leather merchant in the business founded in New York City by his grandfather, Maria’s father served in 1865 in the Connecticut House of Representatives.

After graduation, she returned to live with her family at “Blachley Manor,” the family home on Noroton Hill in Stamford. In 1870, she married Timothy Hopkins Porter, a Yale graduate and Wall Street banker and broker, who was 21 years her senior. Maria Louisa and Timothy Porter had 3 sons: Louis Hopkins; Blachley Hoyt and Arthur Kingsley. As had their father, all three attended Yale. Arthur Kingsley Porter, the youngest son of Maria Louisa Hoyt Porter, was eight when his mother died, in Stamford, on December 13, 1891, at the age of 44. Timothy Hopkins Porter died in Stamford on January 1, 1901.

Maria Hoyt Porter’s sons all met with dire calamities. In the summer of 1895, Louis and Blachley, hiking with a friend in the Grand Canyon, took refuge from a storm under a rock ledge, which, struck by lightning, fell on them. Blachley was killed instantly, and the other two hikers suffered severe injuries. Louis partially recovered and graduated from Yale the following spring. In 1933, Arthur Kingsley Porter, an art historian, medievalist and professor of art history and medieval studies at Harvard, disappeared while walking along the seacoast in Connemara. His wife believed he had accidentally fallen into the sea, but there were also speculations that, reportedly troubled with depression, he had committed suicide or intentionally disappeared to start a new life in Europe. Kingsley Porter’s house in Cambridge, left to Harvard University, later became the president’s house. He and his mother, Maria Louisa Hoyt Porter’68, are buried in Woodland Cemetery in Stamford, Connecticut.

Cornelia Porter Leland (1844-1933)

Mechanicville, New York

Cornelia Porter Leland ’68 was born in Bath, New York, on November 11, 1844, to Ziba A. Leland and Abigail Porter Leland. A native of Chester, Vermont, her father attended the University of Vermont and Middlebury College and later studied law in Schenectady and Utica, New York. A judge in Steuben County, New York, he served two terms in the New York State legislature. Cornelia had one brother, John Porter Leland. Living at the family home on the Hudson River in Mechanicville, New York, she attended the newly established Mechanicville Academy before joining the first students at Vassar.

In a ceremony on October 23, 1889, in Waterford, New York, Cornelia Leland married the Rev. Robert Scott, an Episcopalian minister from Beatrice, Nebraska. A graduate in 1865 of Princeton Theological Seminary, Rev. Scott had come to the Beatrice congregation in 1886. Among his accomplishments was the erection, in 1889, of the highly lauded Christ Episcopal Church. The Scotts moved from Nebraska to DeLand, Florida, in 1891, and between 1909 and Robert Scott’s death, in October 1915, the couple divided their time between DeLand and a home in Williamstown, Massachusetts. The Woman’s Who’s Who of America (1914-15) notes that Cornelia “was a member of the Vassar Alumnae Association, the Woman’s Auxiliary to the Board of Missions, the Nantucket Maria Mitchell Association, Daughters of the American Revolution and the Woman’s Club in Deland, FL.”

Cornelia Leland Scott maintained an interest in her college, attending Commencement in 1908 with several classmates, forty years after their own. She also took part with four of them—“fifty per cent,” Vassar Quarterly noted, “of its present membership”— in the class’s “almost impromptu and wholly delightful” 55th anniversary in 1923, the highlight of which was the unveiling of a memorial for their “much loved and honored classmate, Mary Watson Whitney.” Cornelia Leland Scott died, after a prolonged, debilitating illness, on February 21, 1933, in her 89th year.

A Vassar friend, Jessie F. Wheeler ’82, remembered Cornelia Leland Scott in Vassar Quarterly at the time of her death: “With her niece, Miss Abbie Porter Leland of New York City, she made her last trip abroad in the summer of 1925. She was always a keen student of affairs, had a brilliant and versatile mind, a remarkable vocabulary and a beautiful voice.”

Louise Friend Parsons (1846-1911)

East Gloucester, Massachusetts

Louise Friend Parsons ‘68 was born on August 8, 1846, in East Gloucester, Massachusetts, one of four children of William Parsons, Jr., a wealthy fishery owner and Martha Hale Friend Parsons. The Parsons ancestors, originally from Devonshire, England, had been in Gloucester for over two centuries, William being a descendent, on his mother's side, of William Coas, a privateer ship captain in the Revolutionary War who had been captured, imprisoned in Nova Scotia, and later lost at sea. When Louise was five-years-old, her mother died, and her father married Mary Eliza Somes. Two of Louise's siblings died in the 1850's, Willie at five in 1856, and Martha of typhoid fever in 1859. Another sister, Annette Pulsifer, married John Stanley, a high school teacher from Concord, New Hampshire. After 3 years in Concord, they returned to Gloucester and John took over the fish and grocery business when Annette's father died in 1883. Louise and Annette would later join the Daughters of the American Revolution.

In 1865, Louise graduated from Gloucester High School, studied at Salem Normal School, then enrolled at Vassar where she studied languages, graduating in 1868 and receiving the college's first master's degree the following year. The notes for her master's thesis in astronomy (entitled "Les Nebuleuses") are in the Vassar archives. She taught school in Charlestown, Massachusetts (1871 to 1873) and Providence, Rhode Island (1878), before marrying the widower Edward Smith Eveleth, a physician at the Albert Gilbert Hospital in Gloucester. Edward had attended the Phillips Exeter Academy and had recieved his medical degree from Columbia. Fluent in several languages and widely read Louise continued to teach. Robert Browning was a favorite author, and Louise was a leader in the Gloucester Browning Club. John and Louise occasionally traveled abroad in their later years, including a trip to England in 1904. Louise died of cancer on June 21, 1911, and was buried in Gloucester's Oak Grove Cemetery.

In an obituary appreciation Rev. George F. Beecher noted of Louise: “Mrs. Eveleth felt at home in the presence of the great minds of literature. She never ceased to be a student. Throughout her years, she not only read over what men of letters said but she weighed their ideas and noted the forms of expression.”

Mary Prentice Rhoades (1848-1919)

Ithaca, New York

Mary Prentice Rhoades ’68 was born on April 6, 1848 in Geneva, New York, the daughter of Dr. Sumner R. Rhoades, a physician, and his wife, Susan Prentice Rhoades. Before coming to Vassar, she prepared at the Ithaca Academy, some 50 miles from her home, and at the time of her attendance the largest school of its type in New York State. After graduating from Vassar as class salutatorian, she taught for three years at Ithaca before assuming a teaching position in Columbus, Ohio.

In 1873 she returned to New York State, where she taught in Syracuse until 1879, when she moved to the recently established normal school in Brockport, New York. At Brockport, she was a preceptress and teacher of English until her retirement—with certification under the state’s new retirement annuity plan— in 1911. At her retirement she was lauded as “very close to the hearts of the alumni of the institution, to all connected with the school and to the townspeople.” The Brockport Republican also noted, “Her influence over the students of the normal was very great, and she commanded their love and respect.” Mary Prentice Rhoades died in Syracuse on July 6, 1919.

Shortly after her graduation Mary Prentice Rhoades was one of three alumnae selected in June 1871 for a committee charged with communicating the wishes of alumnae for representation on the college’s board of trustees, a wish that was realized in 1883. In later years she was a frequent visitor to Vassar and a distinct presence among the alumnae. Along with several classmates she attended Commencement every few years, and at the alumnae luncheon in June 1908—40 years after her graduation— reported Vassar Miscellany, she “told of Vassar as it was when she was in college.”

Mary Reybold (1845-1878)

Delaware City, Delaware

Mary Reybold ’68, the daughter of William Reybold and Beulah Compton Reybold, was born February 5, 1845, in Delaware City, Delaware, just south of Wilmington on the Delaware River. Of German origin, Mary’s paternal ancestors immigrated to Philadelphia in 1777. The family later moved to Delaware, where her grandfather, Philip Reybold, was known as “Major Reybold” after his service in the Delaware Militia during the War of 1812. His son William, Mary’s father, also a prosperous farmer, was the president of the family steamship company and served on the board of the Delaware City National Bank.

Mary Reybold grew up on her parents’ farm near Delaware City. At Vassar, she was a member of the self-defined “Hexagon,” the six members of the Class of 1868 who had studied astronomy with Professor Mitchell in each of their years at Vassar. After graduation she and Louise Parsons ’68 were appointed to a year of postgraduate study at Vassar, its first two “resident graduates.”

In the summer of 1869, Mary travelled to Iowa as one of Maria Mitchell’s observers of the solar eclipse that would occur in August. Professional and amateur astronomers from all over the country were headed for the Midwest, causing Professor Mitchell to muse that all observatories “must have been left undirected.” Setting up their camp on the grounds of the Burlington Collegiate Institute, two students were stationed at each of the 3 telescopes with a seventh positioned on top of the College building to observe general effects. Mary Reybold was stationed at the 2½ inch Dolland telescope, where she made notes during the eclipse.

Mary lived with her family in Delaware City until her marriage there on January 22, 1872, to Dr. Stiles Kennedy, a physician from St. Louis, Michigan. Born in Kentucky in 1838 and schooled at the Milford Academy before earning his medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania in 1859, he had served as a physician in the Confederate Army during the Civil War. Sent in September 1862 by General Lee to Frederick City, Maryland, under a flag of truce after the Battle of Antietam, Kennedy assisted Union physicians treating the wounded of both sides.

Stiles and Mary Kennedy were remembered, in The Biographical Memoirs of Gratiot County [Michigan] (1906), as “long . . .known for their enterprise, integrity and wealth.” In addition to his support of several successful local industries, Dr. Kennedy published widely on medical topics. Mary bore three children: William, on May 28, 1873; George, on May 23, 1876 and Mary, on March 17, 1878. A few days later, on March 22, 1878, Mary Reybold Kennedy died, at the age of 33 and only 10 years after her graduation—the 5th member of her graduating class to pass away.

Mary Reybold’s notes on the Iowa eclipse, appearing along with those of the other Vassar observers in Reports of Observations of the Total Eclipse of the Sun, August 7, 1869 (1877) bordered on the poetic:

Body of moon of inky blackness. Cusps sharply defined.

The light did not appear like ordinary sunlight diminished.

4h 54m Venus seen.

During totality two intensely bright lines were seen across the corona to moon’s disc,

one from the right and one from below, as seen by the naked eye.

Fire flies seen. Birds flew around as if lost. Crickets chirped.

Maria Stagg (1845-1919)

Paterson, New Jersey

The daughter of John Stagg and Maria Tice Stagg, Maria Stagg ’68 was born in Paterson, New Jersey, on August 4, 1845, the sixth of seven children, three of whom died in early childhood. Descended from 17th century settlers of New Jersey, Maria’s father was an active builder and craftsman, praised in his obituary as “an industrious man and an upright citizen.” Having prepared to join the first group of Vassar students at the Amenia Seminary for Young Women in Amenia, New York, Maria entered Vassar in September, 1865, and graduated with the Class of 1868. Maria married her second cousin, Canadian businessman Hugh O. Fulton, on October 18, 1871. The couple lived briefly in Meaford, Ontario. Returning to Patterson in 1873, the Fultons had three children: John, born in 1872; Anna, (1875); and Kate Stagg Fulton (1880), a member of Vassar’s Class of 1903.

Maria Stagg Fulton returned to the campus from time to time. At Commencement in 1908, she observed the 40th anniversary of her graduation with seven classmates—Louise Parsons Eveleth, Cornelia Leland Scott, Mary P. Rhoades, Martha S. Warner, Sarah Glazier Bates, Isabella Carter Rhoades, and Elizabeth R. Beckwith. Mrs. Fulton’s husband passed away on Oct. 26, 1894, and she died of bronchial pneumonia in Paterson General Hospital, at the age of 74, on January 16, 1919.

At the time of her death, Vassar Quarterly reported that Maria Stagg Fulton was “said to be the first woman of her city to become a college graduate.”

Sarah Tappan Stoddard (1847-1873)

Oroomiah, Persia

The second daughter of Harriette Briggs Stoddard and Reverend David Tappan Stoddard, Sarah Tappan Stoddard ‘68 was born on February 11, 1847, in Oroomiah, Persia (later, Urumieh, Iran). Descended from pioneer New England ecclesiastic and social leaders, David and Harriette were also well-educated, he at Williams and Yale and she at Bradford Academy in Haverhill, Massachusetts, where she later taught. In 1843 Rev. Stoddard was teaching at Mount Holyoke Seminary, later Mount Holyoke College, when he and Harriet were married. The couple answered a call from the American Board of Foreign Missions to Persia, where Reverend Stoddard directed a school for Nestorian boys in Oroomiah and later in Mt. Seir. Their first daughter, Harriet, was born in Oroomiah in 1844. In August, 1848, both Rev. and Mrs. Stoddard suffered severe cholera and were forced to leave Oroomiah. Mrs. Stoddard died in Trebizon, Turkey, where she was buried.

Two months after his wife's death, Rev. Stoddard returned with his daughters to the United States, where he declined the offered presidency, in 1850, of Mount Holyoke Seminary. The following year he married Sophia Hazen, the associate principal (president) at Mount Holyoke, who had served as acting principal during the terminal illness of the school's founder, Mary Lyon. With his new wife and eldest daughter, Rev. Stoddard returned to missionary work in Persia. Four-year-old Sarah remained in Marblehead with her maternal grandparents. In 1852, Sarah returned to Persia with a missionary couple, Edward and Ann Crane. Four years later, in 1856, Rev. Stoddard became ill with typhoid fever and died at Mt. Seir in January 1857. Sarah's sister Harriett died two months later. Some of Sarah's childhood correspondence, including a moving note informing her Massachusetts family of the deaths of her father and sister, were preserved in the collected papers of her aunt, Caroline Atherton Briggs Mason, a celebrated suffragette and poet. Sarah returned to Northampton with her stepmother, and they lived for a while with Sophia's family in Thetford, Vermont. In the early 1860's, they returned to Massachusetts and Sophia rejoined the faculty at Mount Holyoke, serving again as associate principal.

Sarah Tappan Stoddard attended Mount Holyoke Seminary from 1863 to 1866. She entered Vassar in 1866, graduating in 1868. During her time at Vassar, Sarah's stepmother served as the acting principal of Mt. Holyoke. After leaving Vassar, Sarah taught in Charlestown, New Hampshire, for two years and later in Northampton, Massachusetts, until her death from consumption on July 1, 1873, at the age of 26.

Throughout her life Sarah Tappan Stoddard remained an honorary member of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. She also was a member of the national society of Daughters of the American Revolution. The inscription on her headstone at the Bridge Street Cemetery in Northampton reads: "He loved me and gave himself for me."

Helen Landon Storke (1845-1931)

Sennett, New York

Helen Landon Storke ‘68 was born on January 6, 1845, in Sennett, a village in Cayuga County, New York, to Elliot Grey Storke and Hannah Sophia Putnam Storke. A self-educated teacher at sixteen, her father was the county superintendent of schools between 1842 and 1846 and later entered publishing, first with a New York City firm and later with his own Auburn Publishing Company. The author of a successful work on domestic and rural affairs, he published in 1863 and 1865 A Complete History of the Great American Rebellion, a two-volume history of the Civil War, written with Dr. Linus Pierpont Brockett. In 1866 he assisted in the organization of the Merchants Union Express Company, and in 1867 he founded the Metallic Plane Company in Auburn, a manufacturer of iron bench and block planes, some of his own design. Helen's two sisters, Sophia and Isabella, became teachers, and her oldest brother, Henry, joined his father in his publishing firm and later was prominent in the introduction of the telephone in New York State. Her younger brother, Frederic, attended Amherst College and played professional baseball in Auburn for a while before beginning a law career.

Enrolling at Vassar in 1867, Helen studied Latin, German, and, with Maria Mitchell, astronomy. A member of the Hexagon—the six students in the Class of 1868 who had studied astronomy with Mitchell during their entire time at Vassar—Helen read a poem, "Days,” at her graduation. She taught in Auburn, New York, and in 1869 she joined Mitchell and other members of the Hexagon on a trip to Burlington, Iowa, to view a solar eclipse. The group’s notes on the eclipse were subsequently published in the American Ephemeris and Nautical Almanac, the country’s official astronomical publication.

Helen returned to teach in Auburn and then studied Latin and German in Berlin for a year, returning in May 1875. On the faculty at the new Wellesley College in 1975-76, she accepted the post of principal in the Women's Department at Olivet College in Michigan. She later taught at the Normal School in Whitewater, Wisconsin. In 1880, she became the lady principal at West Cleveland High School in Cleveland, Ohio, teaching Latin and German there for forty years. In her later years, she returned to Auburn.

Helen Storke kept in touch with the college, attending Commencement ceremonies and serving on the Principal Committee of the Associated Alumnae. She continued German studies during summers, in Western Reserve University in 1900, at the University of Chicago in 1901, and in Greece during a leave of absence in 1909. During the first World War, she volunteered with the Red Cross. She kept in contact with Vassar friends, notably her classmate, Martha Warner, to whom she wrote only a week before her death, at 85, at home in Auburn on January 31, 1931.

Martha Spooner Warner (1847-1944)

Burlington, Vermont

The daughter of William Warner and Harriet Leach Warner, Martha Spooner Warner ’68 was born in Burlington, Vermont, on July 15, 1847. In 1855 her father, a graduate of Middlebury College and a railroad executive, moved his family to Detroit, where he co-founded the Detroit Bridge and Iron Works. With her sister, Harriette, known as “Hattie,” Martha, called “Mattie,” attended Miss Sarah Hunt’s Select School for Girls in Detroit. They arrived together in Poughkeepsie on September 20, 1865. Harriette was one of the four students identified in 1867 as graduating seniors. After a third year, Martha graduated with the Class of 1868. Their sister, Helen, who had joined them at the college in 1866, was also a graduate in ’68.

A month after the sisters’ graduation, a cascade of difficulties began when William Warner, superintending the construction of an iron bridge across the Mississippi River in Quincy, Illinois, died in an accident on July 29. Martha, who had returned to Detroit, subsequently suffered a severe back injury that permanently limited her mobility, and the death in 1878 of Harriette’s husband of eight years obliged her and her three children, William Warner, Helen Louise and Elizabeth Lorainne, to return to Detroit. Hattie immediately began career in teaching, and the oversight of the household at 74 Pitcher Street, including that of her widowed stepmother, Fannie Warner, fell largely to Martha. In 1911 Vassar Quarterly noted that Martha was president of Detroit’s Wednesday History Club, treasurer of the Vassar Students’ Aid Society and “home-maker for her sister and two nieces, who are all teachers.”

Mattie remained faithful to Vassar, returning in 1889 on early days at Vassar at the dedication of the Alumnae Gymnasium, in 1897 to Commencement and again in 1908 at the 40th anniversary of her graduation. She was class secretary from 1922 until 1942, when the death in 1941 of Anna Baker Brooks left her the only living member of the Class of 1868. Harriette Warner Bishop died in April of 1944, and Martha Spooner Warner passed away on August 18 of that year.

!n Vassar Quarterly in 1889, Martha Spooner Warner Recalled how she and Hattie, “two girls, travel-worn and weary,” alighted from the Albany train “to the platform of the Poughkeepsie station, and looked hesitatingly about them.” They proceeded to the college: “We drove up in an omnibus full of girls with their fathers and mothers. I wished I were anywhere else in the world. I never dreaded anything so much as I did getting there. We came in sight of the building, and it looked just like the picture”

Helen Frances Warner (1842-1905)

Pittsford, Vermont

The eldest of the three daughters of William Warner and Harriet Leach Warner who attended Vassar, Helen Frances Warner ’68 was born in Pittsford, Rutland County, Vermont, on December 15, 1842. In 1855 her father, a graduate of Middlebury College and a railroad executive, moved his family to Detroit, where he co-founded the Detroit Bridge and Iron Works. Helen’s mother died in 1859, and her father subsequently married her mother’s sister, Frances Leach.

Helen’s sisters, Harriette and Martha were among the first 353 students to enter Vassar in its first year, and Harriette was one of the four first graduates of the college, in 1867. Helen, who had graduated from Detroit High School in 1863, entered Vassar in 1866 as a preparatory student. She joined her sister Martha in the graduating Class of 1868. A month after the sisters’ graduation, Helen’s father died in an accident while superintending the construction of an iron bridge across the Mississippi River in Quincy, Illinois.

After graduation, Helen attended the Women's Medical College in Philadelphia and later studied in the medical department at the University of Michigan, from which she got her degree in 1872. Dr. Helen Warner subsequently traveled to Europe, where she attended medical courses for two years in Paris and Vienna. Returning to Detroit in 1874, she became first woman in the city to practice the modern medicine known as allopathic medicine.

Helen Warner was a leader in the city where she lived and practiced medicine. One of the two founding physicians in 1874 of the Free Dispensary for Women and Children, she spoke frequently at the annual Fort Street Church “mother’s meetings,” served as a lecturer in physiology at the Detroit Seminary at the founding of that “academic and collegiate” institution for women in 1889, and was praised in the Detroit Free Press the following year, in a review of “Detroit’s Women Doctors” as one of the three woman physicians who had “helped lay the foundation upon which they and others have built inch by inch the fair structure of woman’s success as a ‘healer of the sick.’”

Ill health caused Dr. Helen Warner to retire from her practice in 1900. She died from interstitial nephritis at her home at 53 Adams Street in Detroit on October 23, 1905.

An appreciation of Helen Warner appeared in the Detroit Free Press in 1890: “A graduate of Vassar, before commencing her medical studies, and an enthusiastic reader, Dr. Warner brings to her profession all the aid that culture could give. Although a native of Vermont, she came to Detroit at the age of 12, and looks upon the city as her native place.”

Mary Watson Whitney (1847-1921)

Waltham, Massachusetts

Mary Watson Whitney ’68 was born in Waltham, Massachusetts, on September 11, 1847, the daughter of Mary Watson Crehore Whitney and Samuel Buttrick Whitney, a successful real estate entrepreneur. She attended public high school in Waltham and was a private pupil at a nearby Swedenborgian school. At Vassar, she was president of the math club, active in the croquet and chess clubs, a contributor to student publications and a performer in dramatic productions. "Her classmates,” a biographer said, called her “Pallas Athena, Our Goddess of Wisdom." An editor of The Transcript, the first student journal, and president of the class in 1867, she was a member of the Hexagon, the six members of the Class of 1868 who studied in Maria Mitchell’s astronomy courses in each of their Vassar years. Miss Mitchell’s father, who lived with his daughter in the Observatory, confided to a friend shortly after her graduation, “ to Mary Whitney is to be awarded the palm of unrivalled qualities.”

Mary’s father died suddenly on May 13, 1867, and, shortly thereafter, her elder brother Elisha, missing for months in the South Seas, was conclusively declared lost. After reading at Commencement an essay, “Verboten,” in German, Mary returned to Waltham to aid her mother with her three siblings. Teaching for a year in nearby Auburndale and joining Maria Mitchell’s observers of the solar eclipse in Iowa in the summer of 1869, Mary accepted the invitation of Harvard College Professor Benjamin Peirce to study the algebra of quaternions and celestial mechanics over the two following years.

Mary Whitney returned to Vassar in 1872 to assist Maria Mitchell in determining the precise latitude of Vassar’s Observatory with a zenith telescope loaned by the U. S. Coast Survey. When her sister Adaline, a Vassar graduate in 1873, studied medicine in Switzerland, Mary joined her and the family. In Zurich, she attended lectures in Synthetic Geometry and Celestial Mechanics.

Mary returned to Vassar in 1881, at the request of Professor Mitchell, whose health was waning. She shared in the teaching, oversaw the observations and made sure that the time as read from the Observatory’s astronomical clock was accurate to the second. Confident that the qualities of Vassar astronomy would be sustained, Maria Mitchell signaled her retirement in 1887 and conveyed her professorship to her former student in 1888. Whitney brought the Observatory’s work in the greater world of science and scholarship.In 1910, Mary Watson Whitney suffered a cerebral hemorrhage that left her partially paralyzed. In 1915— as had Maria Mitchell— Mary Whitney surrendered her post to a former student, Caroline Furness ’91. She died of pneumonia at home in Waltham on January 21, 1921. In a memorial to her mentor, Furness quoted one of Whitney’s Vassar classmates: “From the first day of her college life, she moved through her appointed orbit as serene and calm, and as true to the line as the stars she loved so well.”

Mary Watson Whitney, her classmates, Sarah Glazier and Sarah Louise Blatchley, and the poet herself comprise the opening line of the verse Maria Mitchell wrote en route to New York City to say farewell to her departing students:

Sarah, Mary, Louise, and I

Have come to the crossroads to say good-bye;

Bathed in tears and covered with dust,

We say good-bye, because we must;

A circle of lovers, a knot of peers,

They in their youth and I in my years,

Willing to bear the parting and pain,

Believing we all shall meet again;

That if God is God and truth is truth,

We shall meet again and all in youth.

Genevieve Blanche Whittemore (1848-1876)

Sherburne, New York

Genevieve Blanche Whittemore ‘68 was born in Sherburne, New York in 1848, to Henry W. Whittemore and Mary Jane Calkins Whittemore, both from landed families in Chenango County. In the early 1850's, the family moved to Little Falls in Herkimer County, where Henry worked as a toll collector and express agent on the Erie Canal.

Genevieve (often known as "Jenny") came to Vassar in 1866 and graduated in 1868. She moved back to Little Falls and later taught school in Steuben and Chautaqua Counties (Bath and Forrestville). On October 28, 1874, she married Albert Melville Prentice, a Baptist minister and her distant cousin. Their maternal grandfathers, brothers, had raised families only 12 miles apart in Chenango County.

During Jenny's time at Vassar, Albert, a graduate of Madison University—later Colgate—and the Madison Theological Seminary, served as Baptist minister in the nearby town of Rhinebeck. Jenny and Albert lived in Sweden, New York, in 1875, but when she became pregnant, they moved back to Little Falls. After the birth on March 17, 1876 of the couple's son, Ernest Arthur, Jenny contracted Typhoid Fever. She died May 29, 1876, at the age of 28. Jenny and Albert's son was brought up by his Whittemore grandparents.