X-Ray VisionHelping First-Year Students Get Illuminating Views of Renaissance Art

X-Ray VisionHelping First-Year Students Get Illuminating Views of Renaissance Art

How does bombarding an atom with x-rays help scholars study Renaissance art? Students in Adjunct Assistant Professor of Art Christopher Platts’s first-year writing seminar, “Art and Science in the Age of Leonardo and Galileo,” spent a recent afternoon at the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center finding out.

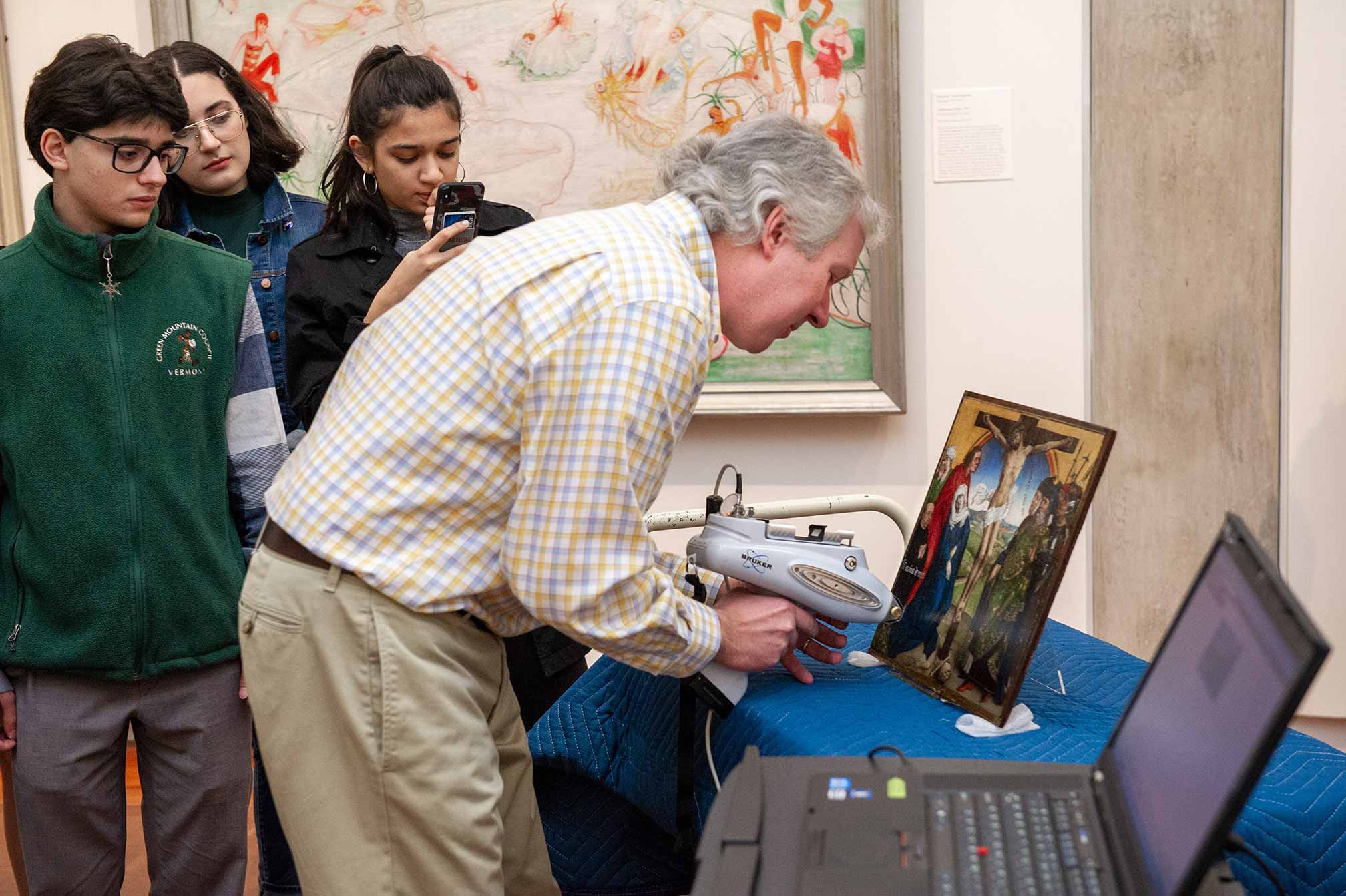

The students gathered in a gallery in the museum to watch Joseph Tanski, Professor and Chair of Chemistry on the Matthew Vassar, Jr. Chair, use an x-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer to determine what elements were present in various pigments in a 15th-century painting currently on display. Aiming the hand-held device at various parts of the painting, Tanski was able to determine that some of the paint contained lead, other pigments contained mercury, and a few contained small amounts of gold.

Before he conducted the demonstration, Tanski gave a brief overview of the science behind it to the students in a classroom in the museum: “When x-rays from the x-ray fluorescence spectrometer knock an electron out of an atom and another electron replaces it, this generates a pulse of energy,” he explained. “This pulse is different for every element, so the spectrometer can detect which elements are present in the sample.”

Platts said Tanski’s findings substantially confirmed his students’ hunches about the kinds of pigments they were likely to find in the painting. Titled Crucifixion by a student or apprentice of noted Flemish Renaissance artist Rogier van der Weyden, the painting was commissioned by a monk who probably wasn’t wealthy enough to afford some of the more expensive pigments, Platts said. “Gathering this data and then interpreting it helped us understand how the painting was made and how the patron who paid for it and the artist who executed it made decisions about using expensive or inexpensive pigments, or to use actual gold in some places while simulating gold with a yellow paint in other places,” he said.

The previous week, the class had visited Rick Jones, Collection Manager at Vassar’s Warthin Museum of Geology & Natural History. Jones helped the students examine and handle the same minerals that Renaissance artists used to concoct their colors 500 years ago. “We also ground up and painted with a few of those minerals, just like those early artists did,” Platts said. “That week we read Renaissance treatises on how to make pigments out of minerals and vegetables. These experiences prepared us for the visit to the Loeb.”

Tanski, who has examined numerous works of art at Vassar’s museum since the Chemistry Department acquired the XRF spectrometer in 2010, said the technology is used widely in the art world to confirm—or dispute—the authenticity of paintings, sculptures and rare coins. “The Met (Metropolitan Museum of Art) would never buy anything without using an XRF or other such tools to determine its authenticity,” he said.

Tanski said he enjoys conducting such demonstrations for Vassar art students. “This kind of multidisciplinary teaching is what we do at Vassar,” he said. “It’s part of our DNA.”

Students in Platts’s class said Tanski’s demonstration had enhanced their understanding of how works of art are created. “Before this class, I never really thought much about the interaction between art and science,” said Lucia Giannamore ’23. “Making paints and crushing stones for pigment is a lot more scientific than I thought. This is one of the great things about a liberal arts education, making connections that you wouldn’t otherwise make on your own.”

Emma Klein ’23 agreed. “Being able to scientifically analyze 15th Century paintings from the Loeb using x-ray fluorescence technology furthered my understanding of the complex makeup of materials that were utilized during that time,” she said. “This crossover of art and science made for an intriguing and exciting lesson.”

T. Barton Thurber, director of the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, said promoting such teamwork between the faculty and the museum staff is part of its mission. “The Loeb Art Center regularly promotes collaboration between the arts and sciences to expand our understanding and appreciation of technical research and the rich artistic legacy available on campus for students, faculty, and the other visitors,” Thurber said. “In the case of the examination of the painting attributed to the Circle of Rogier van der Weyden, one of the most influential northern artists of his time, we are keenly interested to learn more about this intriguing work of art in the Loeb’s collection. Scientific analyses are critical to enhancing our knowledge about it and will be compared with data by other researchers as part of an ongoing international investigation.”