Memorial Conference Celebrates 50 Years of Africana Studies at Vassar

Memorial Conference Celebrates 50 Years of Africana Studies at Vassar

On November 1, 1969, 34 African American Vassar students ended a successful three-day occupation of Main Building after gaining assurances from then-President Alan Simpson and the Board of Trustees that their demands for continued funding and enhanced administrative support for the college’s new Black Studies program had been granted.

Exactly 50 years later, almost to the hour, 10 of those women were back in Main, accepting thanks and congratulations for what they had done from President Elizabeth Bradley. “We are so grateful to all of these courageous, smart and visionary early leaders,” Bradley told those gathered in the Villard Room for the opening of a three-day conference commemorating 50 years of Africana Studies at Vassar. Bradley asked the women to stand, and they received an ovation from the more than 100 in attendance.

The women who had taken part in the occupation of Main and returned for the conference included: Dr. Jettie Burnett ’70, Maybelle Taylor Bennett ’70, Beatrix Davis Fields ’72, LaFleur Paysour ’72, Dr. Sheila Wright-Scott ’72, Dena Henderson Sewell ’72, Dr. Patricia James Jordan ’72, Geneva Kellam ’72, Donna Knight ’74, and Yolanda Sabio ’73.

Throughout the weekend of November 1-3, alumnae/i, students, faculty, staff, and community members took part in the Larry H. Mamiya Memorial Conference Celebrating 50 Years of Africana Studies at Vassar College. The event was named in Mamiya’s honor for nearly four decades of service at Vassar. Mamiya, a former community organizer in Harlem, was Professor of Religion and Africana Studies from 1975 to 2014. In 1979 he launched the college’s prison education program. Mamiya died January 8 at his home in Hawaii.

In her tribute to Mamiya, Stacey Floyd-Thomas ’91, an Africana Studies major, praised him for his leadership as director of the Africana Studies program. “This Japanese-American man stood up for black students,” Floyd-Thomas said. “He walked the walk, spending his life making a redemptive difference. We should not allow Larry Mamiya’s name to be lost in these hallowed halls. May our blessed angel be the wind beneath our wings.”

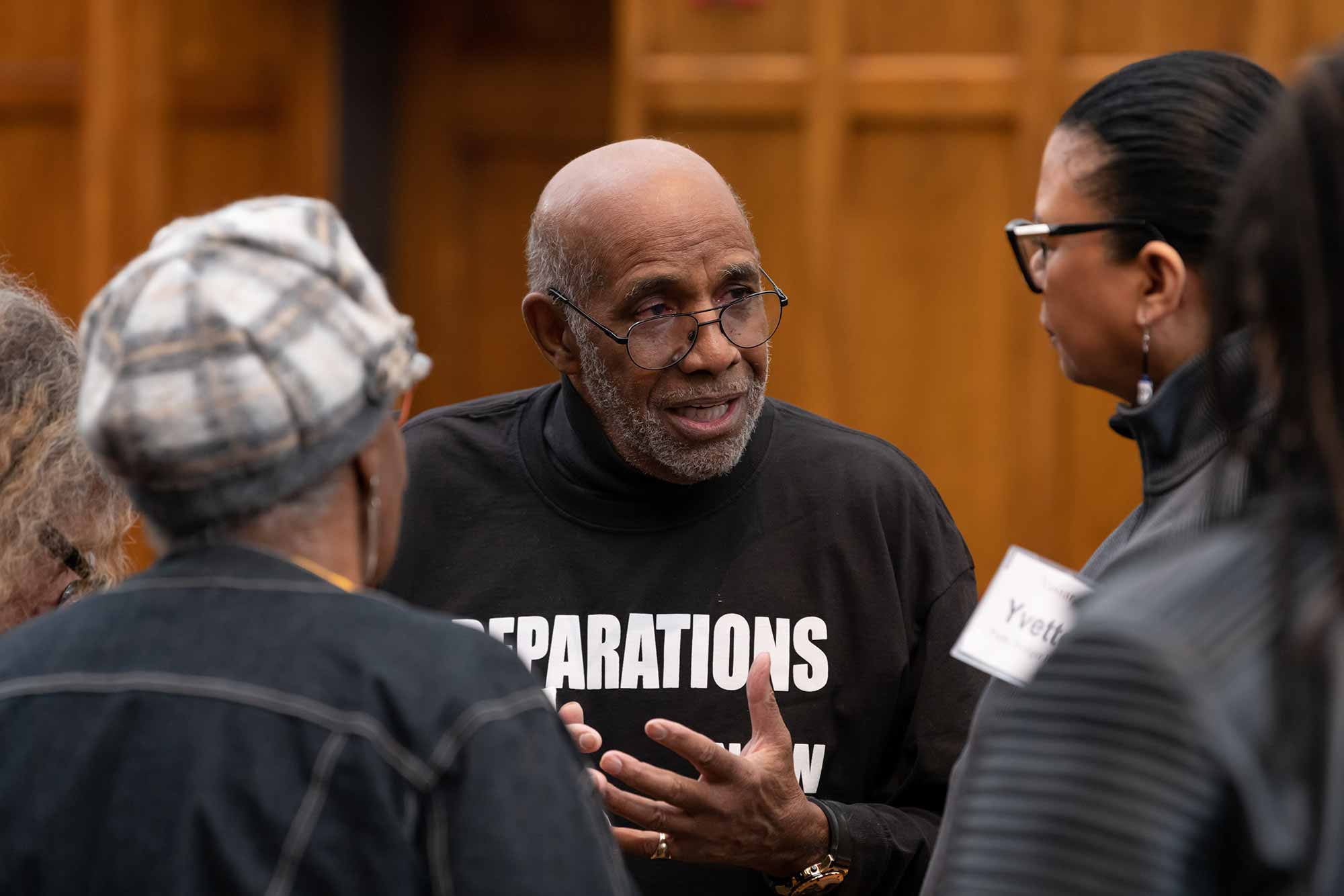

The first director of Vassar’s Black Studies program, Milfred Fierce, was a member of the first panel, titled “Between Reparations and Resilience.” Fierce challenged the current generation of Africana Studies majors—at Vassar and on other college campuses—to join a nationwide campaign for the adoption of HR40, legislation introduced in Congress that would fund the activities of a commission to study how reparations should be made to African Americans, Asian Americans, Native Americans and others whose families have endured discrimination by the U.S. government.

“This Africana Studies generation is standing on the shoulders of previous generations,” Fierce said. “It’s up to them to get the ball rolling to pass HR40.”

In her opening remarks, panel moderator Blanche Bong Cook ’90, a former federal prosecutor and currently a professor at the University of Kentucky School of Law, said she had heard some people question the value of Africana Studies programs. “I had a long and rewarding career that would not have been possible but for the Africana Studies program at Vassar,” Cook said.

The opening address was delivered by nationally renowned writer Saidiya Hartman, a professor of comparative literature at Columbia University and a recipient of the MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant. Hartman read passages from her book Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, which examines the personal lives of black women in Philadelphia and New York City—and their courage to challenge traditional norms.

In response to a question from panel moderator Karina Norton ’20, a current Africana Studies major, Hartman said she was interested in exploring the risks these women made “not to live the straight life and refusing to show up for obligations and duties (such as domestic work) that suck the life out of you.”

Another panelist, Professor of Sociology Diane Harriford, told Hartman her work had “shed light on this topic in ways I didn’t understand before.”

A panel discussion the following day moderated by Samson Okoth Opondo, Associate Professor of Political Science and Africana Studies, examined black studies, black feminism, and recent African uprisings. Author, philosopher and University of Connecticut Professor Lewis Gordon spoke about the truths offered by black and Africana studies programs — as well as the work of some to discredit them as non-intellectual because they deal with difficult and non-traditional subject matter.

Assistant Professor of Africana Studies Jasmine K. Syedullah moderated a panel titled “When They See Us,” which focused on structural isolation, representation, healing, and survival. Syedullah spoke about the criminal justice system’s treatment of African-Americans, which she says “creates funnels into prison,” disconnecting black and brown people from community support. She called for the dismantling of “carceral logic” in order to root out racial oppression.

Glenda Carpio ’91, a Professor of English and African and African American Studies at Harvard University, invited those in attendance to challenge the narratives written by others about African Americans and write their own. Carpio acknowledged that this can sometimes be challenging, in part because of white stereotyping. “It took a long time for people of color to be funny on the page because of the shadow of minstrelsy,” she said. “You have to prove you’re a ‘serious’ artist.”

The final panel of the weekend, titled “The Futures of Freedom,” examined the “push-back” by those in power to deny true freedom to people of color. Lester Spence, Associate Professor of Political Science and Africana Studies at Johns Hopkins University, cited the criminalization of “the squeegee kids,” young men who offer to clean motorists’ windshields at intersections in Baltimore. Spence noted that these young men are threatened “for an entrepreneurial activity that our capitalist society would supposedly approve of.”

Keisha-Khan Y. Perry, Associate Professor of Africana Studies at Brown University, said the issue is not confined to the United States. She noted that recently elected right-wing Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro had instituted policies that threaten gays, women, and indigenous populations in the country. “People have this romantic idea about the races in Brazil, but it has become a white, patriarchal state where blacks and women are expected to know their place,” Perry said.

On the evening of November 2, novelist Aminatta Forna, delivered the keynote address in the Villard Room. Forna, whose political-activist father was murdered during the civil war in Sierra Leone, spoke about narrative identity, resilience and happiness. She noted that we often live out the stories passed down through our families and the culture at large. She encouraged audience members to use their imaginations to envision things as they’d like them to be.

Forna talked about civil wars in Croatia and Sierra Leone, pointing to the difference in how they memorialize war—or don’t. In the case of Croatia, where her novel The Hired Man is set, the war is still very much part of the discourse; but in Sierra Leone, she said, it’s impolite to mention it. She notices a similar tendency to avoid the topic of slavery in the United States—she believes most people in the country have a “selective amnesia” about it. “They’re told about the civil rights movement but not why it was necessary in the first place,” she said.

As the conference concluded, Maybelle Taylor Bennett ’70 said she had no way of knowing what Vassar’s Africana Studies program would look like five decades after she had taken part in the occupation of Main. She said she had returned to the campus many times since she graduated, often for events hosted by the African American Alumnae/i Association of Vassar College (AAAVC). She always looks for the marks the nails made in the first-floor doors of Main when she and her fellow students barricaded themselves inside. “Fifty years later, I feel everything I felt back then,” she said. “And yes, the nail marks are still there.”