Both of Andrea Roberts’ parents grew up in historically significant African American communities. But it wasn’t until she was working as a city planner in Houston, long after she graduated from Vassar in 1996, that Roberts discovered what she calls “a colossal blind spot in history.” In the course of her duties for the city of Houston, Roberts learned that some of these communities had existed within what are now Houston’s city limits, including one, Riceville, where her father had grown up. “It was a precipitating moment that convinced me to return to graduate school,” she said.

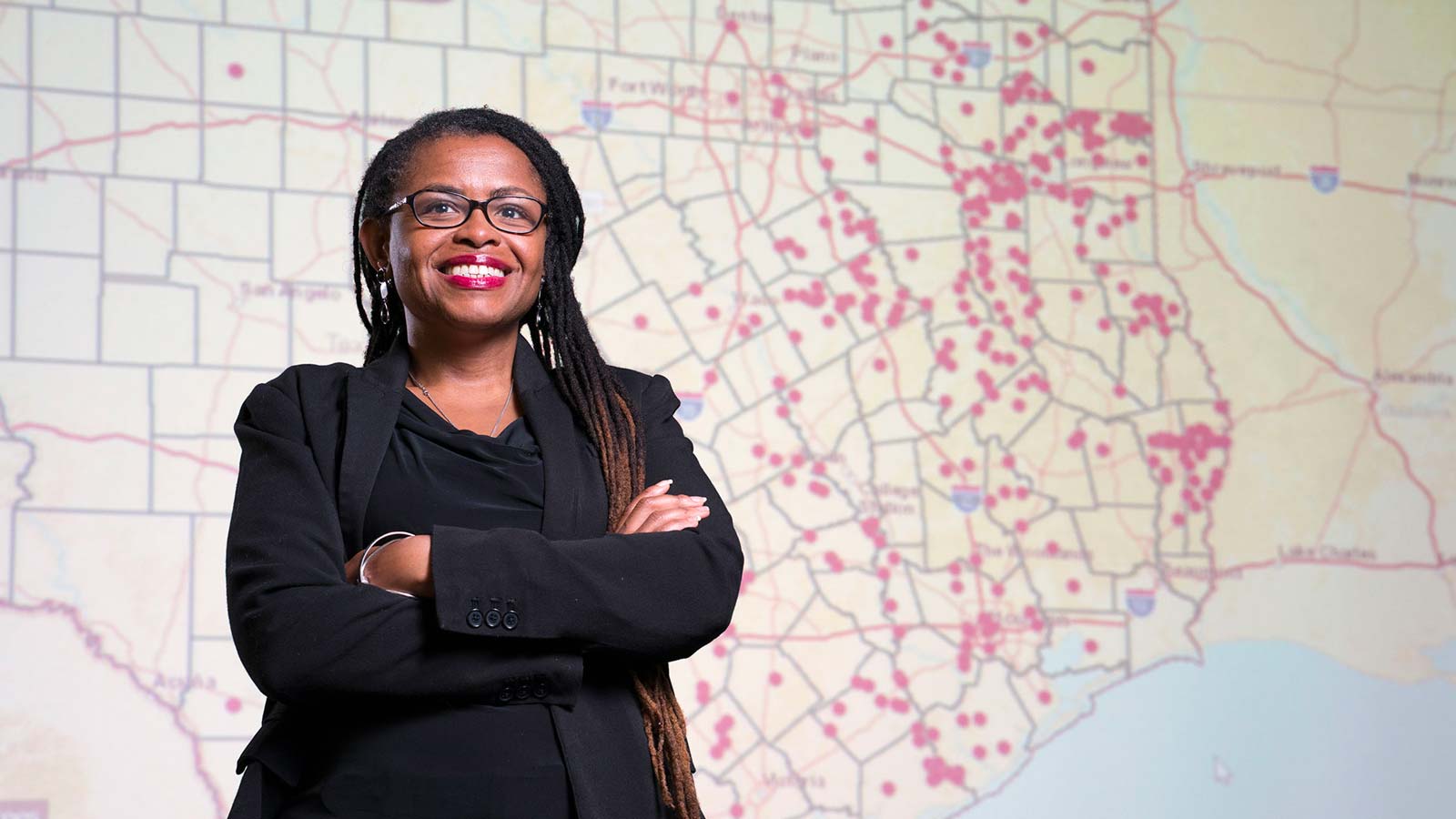

Now an Assistant Professor of Urban Planning at Texas A & M University, Roberts is focusing her research and much of her teaching on the thousands of historically black settlements, often called “freedom colonies,” that sprung up in Texas and almost every other state in the nation following the Civil War.

“These weren’t places where [African American families] were pushed to,” Roberts said. “They were created on purpose and had ‘anchors,’ such as schools and churches and cemeteries around which the settlements were built.”

Many of the settlements on the edge of cities contained all types of businesses and professions, so the residents did not have to rely on whites for such services and amenities.

Roberts interviewed residents and descendants of nine such settlements in Texas for her dissertation, and she’s currently working on a book on the subject that explores some “best practices” for preserving them. She says she believes raising awareness about these settlements is the first step in the process, but more concrete action must be taken. “Just putting these places on the National Historic Register won’t save them,” Roberts said.

Roberts says her work focuses on more than the physical preservation of these settlements. “While I am a planning historian, I’m most interested in thinking about the contemporary relevance to African Americans’ quest for equality and freedom, black agency, and self-determination,” she said. “My work has overlapped with the rise of the Black Lives Matter Movement, and it fueled my consciousness about what safe African American communities look like.”

Part of Roberts’ work involves the creation of an interactive map of such communities. The map has more than 357 of the 557 known communities in the Texas Freedom Colonies Atlas database. Through online crowdsourcing and ongoing ethnographic research, the number of locations added to the map grows daily, Roberts said.

Since Roberts began her research into such settlements in Texas, she’s met other scholars across the country doing similar work about such communities throughout the United States and around the world. One of them, fellow Vassar alum Danielle Purifoy ’06, is conducting postdoctoral research at the University of North Carolina on historical black settlements in that state.

Roberts said she never could have envisioned the explosion of interest in these settlements when she first discovered their existence. “I had a vision for this when I started my work,” she said, “but I had no idea that people from around the rest of the country would have the vision I had.”