Inez Milholland (class of 1909), Harriot Stanton Blatch (class of 1878), Crystal Eastman (class of 1903), Helen Hoy (class of 1899), Julia Lathrop (class of 1880), and Lucy Burns (class of 1902)—these names are well known in the annals of the women’s suffrage movement. But many others marched, mobilized, and even went to jail in dedication to the cause.

Vassar College will be commemorating the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment with a variety of exhibitions and programs that will examine the women’s suffrage movement, its beginnings on campus near the turn of the 20th century, its connections to other movements, its factions, and its sometimes troubling racist history.

Borrowing a phrase from a recent New York Times article on the commemoration events, Miriam Cohen, Professor of History on the Evalyn Clark Chair, notes that the Vassar events should both “celebrate and interrogate”—a term coined from a New York Times article by Devi Lockwood—the women’s voting rights history. She is working on the 100th anniversary programs, including the Archives & Special Collections Library’s exhibition “Votes For Women:” Vassar and the Politics of Suffrage. One planned panel discussion will look at the 19th Amendment, the time before and after its passage, as well as the relation to current events.

“We have an issue of voter suppression right now,” Cohen says.

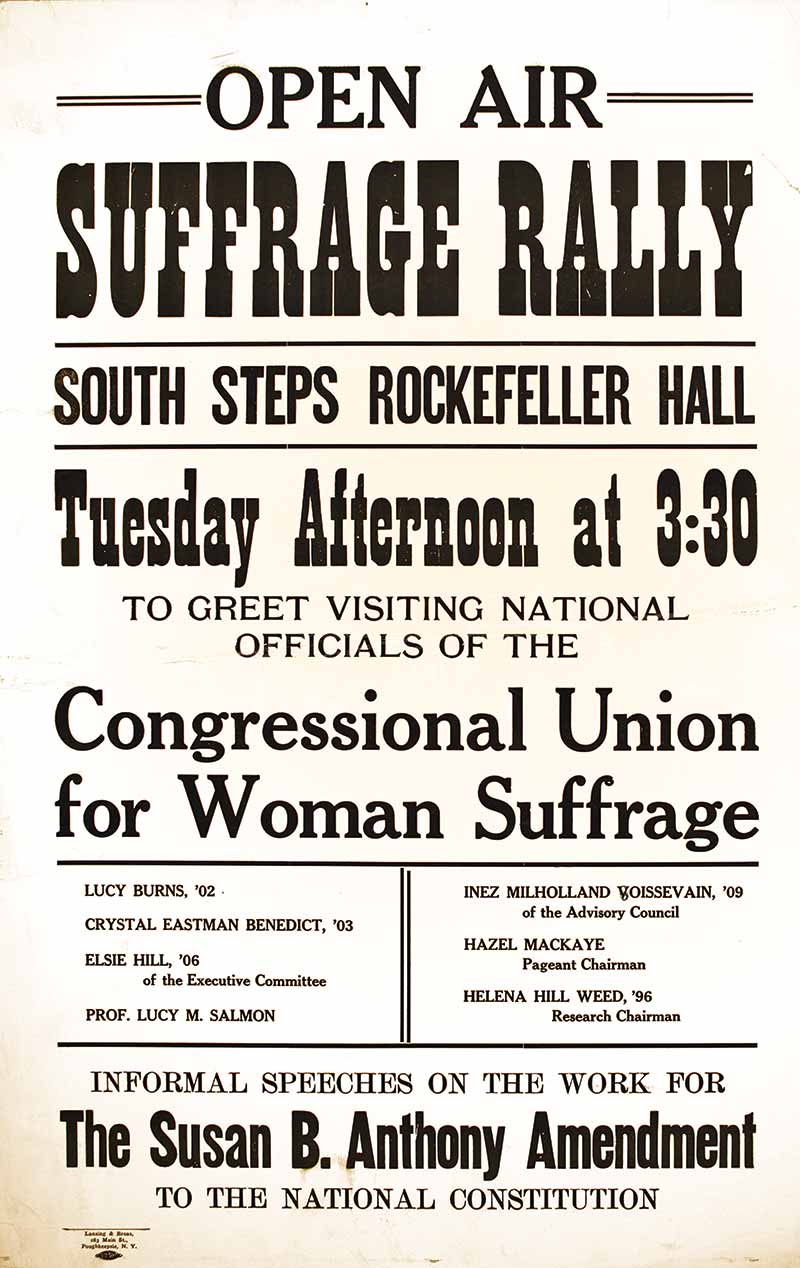

During the most activist years of the women’s voting rights struggle, Vassar’s alumnae were advocating far and wide. Milholland, a well-known suffragist, famously rode a white horse in the 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession in Washington, D.C., and Hoy was corporation counsel for the Equality League of Self-Supporting Women, an organization founded by Blatch, daughter of pioneering suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Burns first fought for women’s suffrage in Britain as a member of the Women’s Social and Political Union, later coming to the U.S. in 1912 to form the National Women’s Party with Alice Paul. Eastman, co-founder of the Congressional Union (it later became the National Woman’s Party) was a feminist activist, a factory investigator and civil libertarian, and Julia Lathrop was a social reformer, suffragist, and the director of the U.S. Children’s Bureau.

While James Monroe Taylor, Vassar’s president from 1886–1914, was an opponent of women’s voting rights and was at odds with students and professors—including Maria Mitchell and Lucy Maynard Salmon—by 1912, women’s suffrage meetings were finally permitted on campus. In 1914, the year Taylor left office, the Board of Trustees allowed the formation of the student Women’s Suffrage Club. Unlike his predecessor, incoming president Henry Noble MacCracken was vocal in his support of the movement and often worked with Lathrop.

“The upswing in interest on campus is a reflection of what was going on in the nation,” Cohen says.

As the movement continued to grow, factions also started to develop and Vassar alumnae found themselves on different paths. The start of World War I, for instance, led some supporters to call a stop to protests in favor of supporting the war effort, while others marched on. Some found themselves supporting more “extreme” measures, including hunger strikes while being jailed. At Vassar, MacCracken supported the mainstream suffragists and opposed the militants. One significant divergence from some of the ideals set forth in the beginning of the movement—which had its birthplace in the Abolitionist movement—is the lack of support for voting rights of black women. Some famous suffragists didn’t want the race issue to interfere with the movement, which prioritized the goals of white women, Cohen says. Others were just bigots.

“Many of them were indifferent, at best, about whether black women got the vote,” she says.

During the 1913 parade in Washington, D.C., a “compromise” was reached within the white leadership of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), that black women could march in the parade, but they would be the last to march. In defiance, Cohen says, Ida B. Wells, the suffragist and civil rights leader then living in Chicago, marched with the white delegation representing Illinois.

Some notable suffragists, such as Milholland, supported Ida B. Wells and the right to vote for black women. This split in the movement highlights another faction—one between those seeking to have voting rights secured at the state level, and those who wanted a federal amendment, Cohen says. As a state issue, many in the north had confidence they would gain the vote more quickly than with a Constitutional amendment, which would require the support of legislators from southern states.

Inherent in the women’s voting rights movement was its ties to other movements, including the labor, immigrant, and civil rights movements.

“It doesn’t stop with the 19th Amendment,” Cohen says. “Its connection to other things is critical.”

The important triumph of the 19th Amendment, according to Cohen, exemplifies the contradictory history of political freedoms in America. Its passage in 1920 occurred at a time of nativist and racist backlash, and concerted efforts to stem the labor movement. The 1920s saw the reemergence of the KKK and the imposition of severe immigration restriction. Jim Crow laws kept many black women and men from voting. At the time, most indigenous and Asian American women could not vote; Latinas also had to struggle for voting rights.

For Eastman, the right to vote was seen as a vehicle to create more social change. In her famous speech, “Now We Can Begin,” given after the ratification of the 19th Amendment, she said that men were likely happy the hullabaloo was over with. “But women, if I know them, are saying, ‘Now at last we can begin.’ In fighting for the right to vote, most women have tried to be either non-committal or thoroughly respectable on every other subject,” Eastman noted. “Now they can say what they are really after; and what they are after, in common with all the rest of the struggling world, is freedom.”