Vassar’s Hidden History video series examines aspects of U.S. history that have been untaught, modified, or erased. It sheds light on historical injustices that are implicated in current disparities in everything from health and financial outcomes to criminal justice.

For the men and women of Celebrating the African Spirit (CAS), every month is Black History Month. For more than three decades, the organization’s predecessor, the Black History Project Committee, has been rewriting history by shedding light on African Americans’ contributions to life in the Hudson Valley since Europeans started settling here more than 400 years ago. And since it morphed into CAS, the group has been taking steps to memorialize the contributions of the thousands of African and African American men, women, and children who were brought up the Hudson River in the 18th and 19th centuries and delivered to slave owners.

On a recent afternoon, CAS board member and treasurer Kalimah Karim stood in the park in the shadow of one of the region’s major tourist attractions, the Walkway Over the Hudson. “I’m told over five million people have come to the Walkway in the years since its operation. I wonder how many of those people know about the slavery that existed right on this spot and throughout the City of Poughkeepsie and the Mid-Hudson Region.” Further, she added, slavery in the Hudson Valley was no benevolent “Hollywood” version of the practice; it was “just as harsh, just as heinous as any Southern slavery you've ever imagined or heard described.”

CAS researcher Susan McIntosh said slavery nevertheless became an intrinsic part of the development of the region and spurred tremendous growth in the Hudson Valley. Some of the group’s markers would contain certain historical information about the role of slavery in the community’s development starting in the mid-18th century.

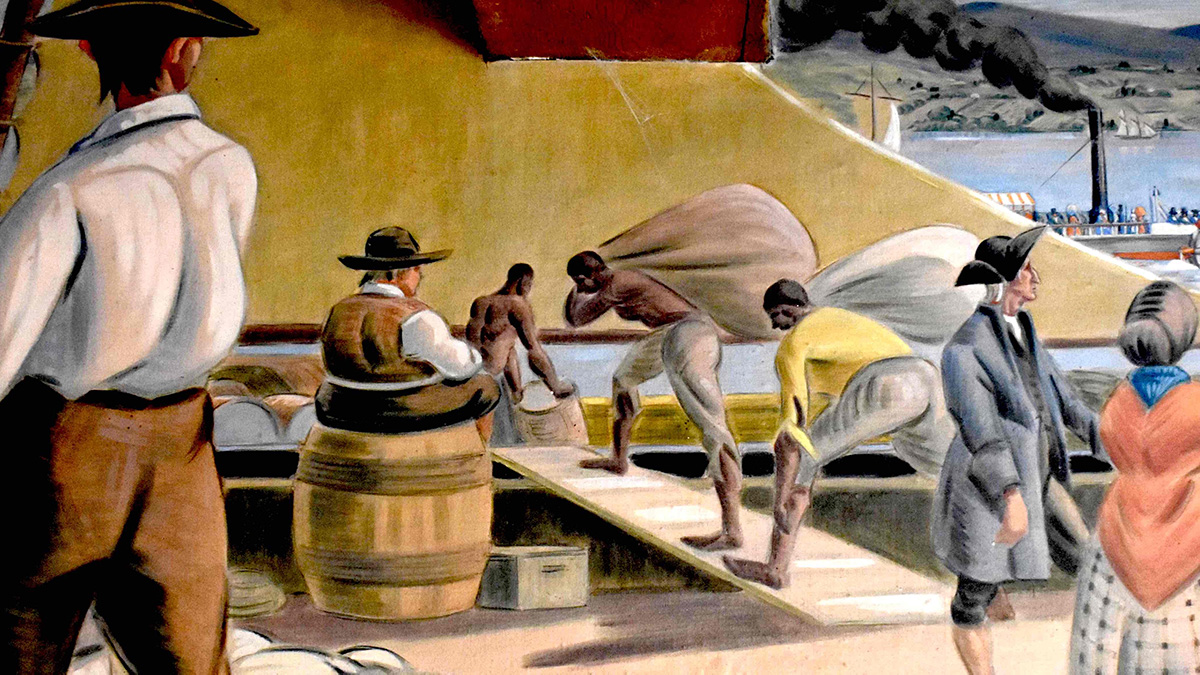

“There was much work to be done,” McIntosh said. “You had the city, where households had slaves for everyday work such as cooking, doing laundry and taking care of the children. And there was also a, lot of industry, so you had carpenters, cooks, teamsters, and coopers working at the local breweries. And of course, at the waterfront you had boatmen and stevedores busy loading and unloading the ships that came through.” River ferries, operating out of what is now Upper Landing Park in Poughkeepsie, also were powered by enslaved men.

The first marker commemorating the contributions of these slaves will be placed in Upper Landing Park soon, and Karim and other members of CAS are working diligently to ensure that more monuments and markers are erected elsewhere in the Poughkeepsie area. Vassar Professor of Political Science and CAS Co-chair Katherine Hite said she hoped the project would help educate local residents about their true history.

“As somebody who's trained in political science, I think a lot about power; who tells the history is about who has the power to tell it,” Hite said. “It's always important to ask, ‘How did that memorial get there? What kind of history is it telling and who decided that that was important to tell that history?’ In the years of the Black Lives Matter movement we are recognizing the deep links between past and present. We are taking a renewed look at the symbolic landscape of the United States, and that has galvanized an important national conversation.”

Other Vassar employees have signed on to help with this effort, as well: Elizabeth Randolph of Vassar’s Communications Department has just joined the CAS Board of Directors, and Bart Thurber, Executive Director of the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, says FLLAC, which frequently supports projects in the local community, has agreed to help fund the markers. Many students have worked with CAS over time, including Zoë Zahariadis ’21, who currently helps with CAS’s communications and social media as a participant in Vassar’s Community Engaged Learning program.

CAS Co-Chair and Co-founder Carmen McGill, a longtime member of the Black History Project Committee, said the decision to shift the group’s focus and make plans to erect the markers and monuments was triggered in part by a proposal presented by Sarah Evans ’18 in a paper she wrote in her senior year for one of Hite’s classes. Evans noted that historians had written plenty about many major figures in the Hudson Valley’s history, such as the Livingston family, while never mentioning the fact that the family owned slaves for more than a century. “When we learned about Sarah’s paper and Katie Hite joined us, we created CAS with a focus on creating these monuments to tell the slaves’ stories,” McGill said.

“It’s important to bring forth this information,” she added. “We have all kinds of symbols and information about the slaveholders but none about those who did the work.”

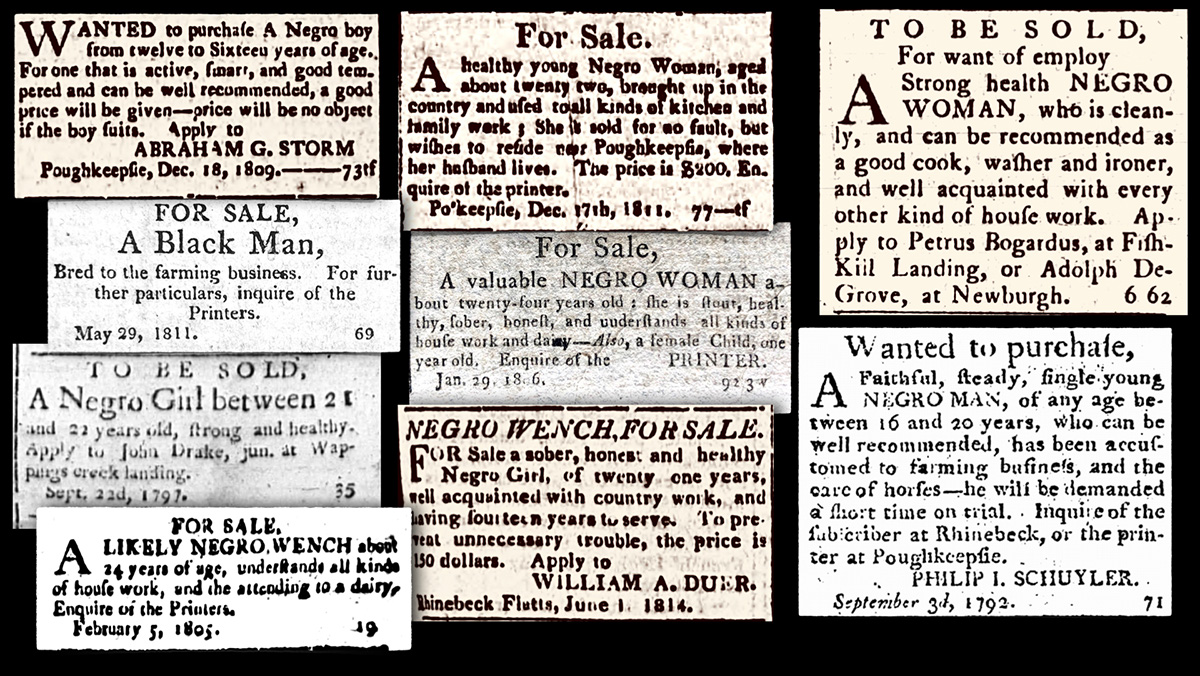

McGill said the exact locations of the other markers have not been determined, but the group is considering placing a major monument to all the enslaved people and their descendants in an easily accessible area in the city’s College Hill Park and erecting at least one marker near the Poughkeepsie Journal newspaper building on Market Street. McGill noted that the newspaper often ran ads for those who were selling enslaved people and for slaveowners who were seeking the runaway enslaved. She said she and other CAS members wanted to solidify their planning and funding sources before they approached city and county officials about the project.

Some preliminary design work is being done by MASS Design Group, an international architectural and design firm. Vrinda Sharma, an associate in the firm’s Poughkeepsie office, and a member of CAS since its founding, said her role thus far has been “listening and contributing some design ideas while embracing an understanding of the history and contributions of the Black community. We want these monuments to act as a catalyst for telling this important story.”

Bill Jeffway, Executive Director of the Dutchess County Historical Society (DCHS), a CAS researcher said, “Suddenly, especially this year, there's been a growing interest in the issues relating to Black history and social justice.” It hasn’t always been easy. Investigating the lives of enslaved or other otherwise marginalized people is often difficult, since the documents that typically aid historians may not be present. The Historical Society, for example, has relied on some unconventional sources to tell some stories that traditional historians have ignored. But he says the effort is worth it to make a significant impact on how people in the region learn about their history.

When concerned people ask him about whether groups such as CAS are “rewriting history,” he often refers them to an observation made more than a century ago by a Vassar professor, Lucy Maynard Salmon, known to many at Vassar as the originator of the saying “Go to the source.” “She literally wrote the book on why it’s important to rewrite history,” he said. “Her proposition is that over time, over generations, we have better ways of coming to understand the past and we might be more truthful about it. There might be new ways to come to understand it or new sources of information. So she would argue that it is important, and she actually says it's the most important thing for any historian, to constantly rewrite history in the sense that we need to look at it with a fresh, contemporary lens and with a view to being as truthful as we can be about what actually transpired.”

Hite said she was convinced that knowing our true history is more than an academic exercise. “We can see the costs of not being truthful about our past and the ignorance on the part of much of our society,” She said. “I'm feeling particularly that way in light of the recent violent insurrection attempt on the Capitol. I think that had a great deal to do with racist ignorance and at least in part, the failures of our educational institutions to do the important work from day one in instruction about the founding of the United States that was in fact built on the twin realities of violent white supremacy as well as of freedom.”

Karim says her involvement in CAS is spurred by a desire to help people understand our history in order to bring about a more just future. “I'm a grandmother. I have a daughter and four grandchildren. I would like their future to be better than my life has been as it relates to how people of color and Black people are treated in this country. I don't want to end my life and things are exactly the same as they were when I was a little girl. My children, everybody else's children deserve better.”