Occupations: The Interconnected Disciplines of Benjamin Busch '91

It’s an article of faith that every actor remembers his first paid role and every military officer remembers his first command. For Benjamin Busch—a Marine Corps veteran who portrayed a paramilitary cop in HBO’s acclaimed series The Wire and a Marine officer in the upcoming Generation Kill — it’s fitting that those memorable moments were one in the same.

Benjamin Busch during the invasion of Iraq, April 2003. “The photo was shot in a dust storm by Sergeant James Letsky, USMCR, my LAV-25 turret gunner,” Busch says, “with my 35mm Canon camera. I was not particularly happy that day.” Inset: Benjamin Busch as Major Todd Eckloff on the set of Generation Kill in South Africa.

Call it a command performance: Busch accepted a commission in the Marine Corps after graduating from Vassar in 1991. While the newly minted second lieutenant had missed the first Gulf War, his men had not. “I walked into a platoon of veterans. I was staring down a pool of alpha males all looking to prove their prowess, and here I was coming from Vassar,” he recalls. “You learn to create a myth about yourself pretty quick. It’s a form of acting. I think all Marine officers and staff sergeants are phenomenal actors — they have to be.” Busch cast himself as a stern, physically fearless, emotionally inscrutable badass, and he played the part well. His audience — 1st platoon, Fox Company, 2nd battalion of the 8th Marines — kept a close, constant watch. Any crack in his façade or unwanted detail revealed could potentially undermine his ability to lead. “I never wanted to compromise my personality,” he says. “I was a pretty weird character — a ‘hair-band’ enthusiast who was interested in history and stone masonry and cubism.”

It was an early indication that Busch, who served two tours of duty in Iraq and was decorated with the Bronze Star, is the exception that proves the rule: making art and military service are not warring impulses. For Busch — a studio art major who enlisted in the Marine Corps, a platoon leader who dove into acting, a recalled reservist who discovered he was an art photographer in a war zone — a seemingly schizophrenic, careening career is actually a continuum. In his photography exhibitions (The Art in War and Occupation), his independent film (Sympathetic Details), and his roles in The Wire and now in Generation Kill, HBO’s miniseries about the invasion of Iraq, which airs in July, he’s deftly managed to combine his vocations. “You need great discipline to be an artist just as you do to be in the military,” says Busch. “They’re different disciplines, but in my soul, anyway, they’re related.”

The only time Busch was unsure of what role to play was when he left the Marine Corps for civilian life in 1996 (he remained in the reserves). “During that transition period I was listing,” says Busch. “You wake up every day and you know you’re supposed to do something — that’d been built in — but you don’t know what.” While his wife, Tracy Nichols ’91, was getting her Ph.D. in history at Georgetown University, Busch spent his days doing backbreaking landscaping work for little more than minimum wage. Had it paid better, he might not have responded to a call for movie extras in Washington, DC, which landed him a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it part as a spectator at a Congressional hearing in the film Contact with Jodie Foster and Matthew McConaughey. On the set of the $90-million movie, something clicked. “The scale was immense, but I had a lot more to deal with as a platoon commander than the director, Robert Zemeckis, did,” says Busch. “I saw that I could do that if I could learn the technical aspects. So I went into extra work to study; it was my film school.”

What followed was a crash course that involved loads of extra work that eventually led to speaking roles, in television shows like Homicide, The West Wing, and films such as The Rules of Engagement, in which Busch was cast as a combat Marine. It was a foreshadowing: his reserve unit was activated in 2003 for the invasion of Iraq.

As a major, Busch commanded Delta Company, 4th Light Armored Reconnaissance battalion, as they pushed deep into Iraq. After Saddam Hussein’s regime was toppled, Busch and his unit expected to leave the country in two weeks. Instead, the order came to hold all of Wasit province, along the Iranian border, indefinitely. “There were no post-hostilities plans, and I think everyone can finally admit that now,” Busch says. Officials from the Coalition Provisional Authority handed Busch $10,000 in cash and a list of tasks so long and so Herculean it would be comical if it weren’t criminal: Form town councils and create local government; rebuild and maintain infrastructure (electricity, water, sewage); recruit, train, arm, and ensure the payment of a police force and a border guard; stop all movement across the border with Iran. Then came the easy stuff: “‘Look for Weapons of Mass Destruction — oh, by the way. Destroy all insurgent elements in your zone. Win hearts and minds,’” Busch says, paraphrasing his orders. “‘Good luck, we’re going back to Baghdad.’”

During the hopeful period between the invasion and the insurgency, Busch was able to fill the vacuum, using his knowledge of tribal politics to negotiate power-sharing arrangements with sheikhs and restore a semblance of normalcy to Wasit. He was forced to rely on a few unorthodox tactics. “I had to fabricate a certain reality to control the environment. I had 150 men and 25 armored reconnaissance vehicles, but I was telling herders I had thousands of Marines in the country—which was true, but they weren’t anywhere near Wasit,” Busch says. “Being Major Busch didn’t hurt either — in a tribal country, your last name was your tribe so obviously I was directly related to the President.” At least some of the success Busch achieved can be traced to an unexpected source. “We were thrown into a civilian battlefield,” says Busch. “That’s why Vassar was a great place for a Marine officer in Iraq to come from. Vassar forces you to think critically and creatively — that’s needed to escape the confines of a template, and Iraq was the one place where we could not use the military’s template.”

Busch’s company did not suffer a casualty in the province. “I trained my unit to believe we were immortal — remember, we thought we’d be gassed and meet hundreds of thousands of conventional forces, and we were going in first,” says Busch. “So we needed the myth that we couldn’t be killed.”

Throughout the tour, Busch felt a familiar urge to record what he saw around. With free moments scarce, he couldn’t draw, but he had brought a 35mm camera with him and he began taking one or two photographs a day. “I wasn’t looking for anything in particular. It’s just the need of the artist to find the art in the environment you find yourself in,” says Busch. “I never held up a patrol to shoot. I walked past 99 great shots I never took; the one I took was the one I felt I could take.”

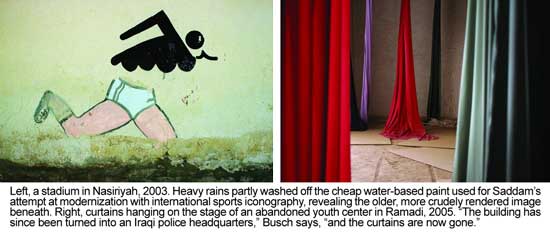

When Busch returned home, he found about a quarter of the film he shot was ruined, scorched by the 130-degree heat. But his former Vassar professor, Harry Roseman, urged him to collect the surviving photos into a show (later titled The Art in War). Iraq provided a compelling context, but the images tend toward the abstract, often hauntingly so, as with his photo of a pile of discarded Iraqi army boots. “A photograph is all about what you leave out,” he says. “The choice you make in cutting this limitless view into a little rectangle, deciding where those edges end, that’s what interests me.”

Busch was growing out his Marine Corps buzzcut when he got called in for his first acting audition since returning home. It hardly seemed like a big break when the director sent him to hair and makeup, and he returned with an extreme, angular shaved-on-the-sides, flat-on-top jarhead do. But along with his expletive-laced invective, the look soon became the signature of his character, officer Anthony Colicchio.

It was supposed to be a one-time, one-line part, but The Wire’s creators, David Simon and Ed Burns, liked Busch’s work, and Colicchio grew into a small but memorable recurring role through the acclaimed series’s five seasons. “There are lots of actors who have more natural ability than a Ben Busch, but there’s damn few who will ever get as much out of his character as he does,” says Burns. “He’s willing to put all the time and effort into making that character resonate.” Embittered by the dysfunctional police department’s failings in inner-city Baltimore, Colicchio was angry and he was vocal. “He’s very unlike me in most ways, but what I liked about him is that he’s very simplistic about his sense of justice,” says Busch. “Baltimore is a world of gray, and he sees it in absolutist terms of black and white, good and bad. There can be no satisfaction for him.” After complaining about his superior’s incompetence and political posturing through the course of the series, Colicchio explodes in an episode that aired in late January. During a drug bust, he drags an impatiently honking commuter from his car, displaying a rage that shocks even his fellow cops. But Busch knew the source. “Your experience is going to find its way into your work,” he says. “With Colicchio I got to openly air the things I had to disguise in Iraq.”

Poorly armored vehicles. Inadequate manpower. A lack of basic supplies. No postwar planning. The seeds of dissatisfaction sowed during Busch’s first tour took root after he was recalled for a second tour in Iraq in 2005. Everything about this deployment was different. For one thing, he was leaving not just his wife but also his three-month-old daughter, Alexandra, behind. After being thrust into the role of rebuilder and negotiator in Wasit, Busch opted to join a civil affairs unit, ready to put his lessons learned in 2003 to work. “I thought I could apply them when I arrived in Ramadi — it was completely naïve on my part,” says Busch. “My mission was to nurture a native solution to a native problem. But I realized I wasn’t going to be effective no matter what I did. There was just too much fighting.”

In 2005 Ramadi, the capital of al-Anbar province and the southern anchor of the Sunni Triangle, was the epicenter of the Iraqi insurgency. Sniper fire was constant. Rocket barrages directed at Busch’s camp were a regular occurrence — a favorite target was the unfortified telephone trailer, which left Marines most vulnerable as they were calling home. During Busch’s seven months in Ramadi, the 1,000-man battalion he was attached to suffered 23 killed, including one of his best friends, and 141 wounded. Two weeks into his tour, Busch became one of those injured when the unarmored cargo truck he was riding in was hit by an IED (improvised explosive device). Five other men were seriously wounded and Busch, laced with shrapnel, earned a Purple Heart. But there was a casualty: the myth of immortality Busch had shielded himself with. “I became so convinced I would be killed it was like having nothing to lose — I was dead already,” says Busch. “I was sure I’d never see a show of the pictures I was taking. It would be a posthumous tribute.”

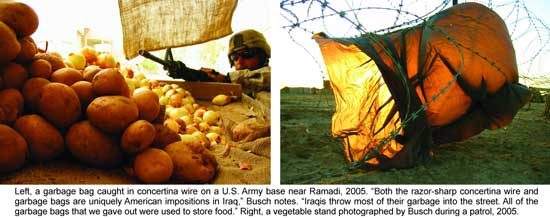

If even that. Busch’s camera was blown to pieces when he was injured. Then his backup was lost to an explosion during another ambush. “Finally, I switched to a smaller digital camera that sat above my ammo pouches on my chest and so I could take my finger off the trigger, grab it and shoot the picture and put it back in a single motion,” he says. “You don’t waste any time in a combat zone.” Busch had to take many of these images, later collected in Occupation, inside secured locations — houses and schools. Despite the limitations, Busch’s photographs are rich in symbolism. One image he shot while taking cover in a market shows a Marine gunner bivouacked behind a wall of potatoes and onions. In another, a starkly backlit garbage bag is snagged on concertina wire, a metaphor for the American presence in Iraq. “If a photo doesn’t say something more than what you see, I don’t like it,” says Busch. “There have to be layers.”

Soon after Busch’s tour ended in February 2006, his father suffered a fatal heart attack, and mortality suddenly became a motivator. “I’d just come out of Ramadi, my father’d died, the feeling was they wouldn’t renew The Wire,” says Busch. “I realized that more than ever time was ticking, running out. I had to hurry to create some kind of future.”

That’s precisely what he did, writing the screenplay for Sympathetic Details in a week and shooting it in just 12 days on a shoestring $50,000 budget, with the help of a half dozen actors from The Wire who signed up to be directed by Busch. About a hitman who wants out of the business, Busch’s film takes a classic story and reimagines it with rich cinematography and multiple layers of meaning. “I wanted to make a meditation on loss and human life,” says Busch. “It also became about fathers and sons and how we can never truly protect the ones we love. I wasn’t writing with that intention, but in retrospect, of course it’s about the things weighing on me.”

Although The Wire returned for a fifth and final season, Busch’s time on it was cut short. The show’s creators, David Simon and Ed Burns, wanted him to head to Namibia and South Africa to appear in their next project, Generation Kill, an unflinching look at the invasion phase of the Iraq War.

Working on the production meant finally crossing paths with a man whose life had run parallel to his for more than 20 years: Vassar alumnus Evan Wright ’87, author of the book Generation Kill, which was based on a series of articles he published in Rolling Stone. Wright had gone to Japan to teach English after college; Busch’s first overseas posting was in Okinawa. Wright was embedded in a Marine recon unit that raced into Iraq; Busch led the Light Armored Reconnaissance unit directly behind it. During filming, Busch and Wright soon found themselves backing each other up to ensure the military details were accurately represented. Busch had read Wright’s book and knew the story, though accurate, would strain some viewer’s credibility. “Their unit was shot to pieces, but didn’t have anyone killed,” says Busch. “No one’s going to believe that — it seems too Hollywood. But then you ask yourself, well, who should be killed off? No one — these are real people.”

That presented other problems, too. As an actor, Busch wrestled with having to play an actual person and one perilously similar to himself. “I played him very honest to my experience,” Busch explains. “Since it was so close to me the director’s adjustments—however necessary—felt like emphasizing ‘acting,’ which is unnatural. I had to get accustomed to that invasion of honesty.”

Busch’s role as the unit’s executive officer isn’t large, but it is precarious. “There are a lot of unusual decisions made by the Commanding Officer,” Busch says, “and the XO only has a moment to say, ‘But sir…’” Indeed, the miniseries exposes plenty of tragic and horrific mistakes—made not just by distant political appointees but by the officers and men on the ground.

“A couple of people portrayed are going to be shamed watching this,” Busch says. “The hard truth is, we aren’t all the people we hope we’ll be when it matters, but it’s important to admit that—artistically and in reality.” Although Busch has now resigned from the Corps, he can’t help but react to Marine failings during the invasion. “I’m horrified,” he says, “but that doesn’t mean it should be hidden—that would be a lie.”

On the set of Generation Kill, Busch approached Burns with an idea for a sort-of follow-up, a screenplay about the occupation, tentatively called Ramadi, and Burns quickly offered to write the treatment with him. “He’s got all the skill in the world,” Burns says of his collaborator. “He’s got that visual poetry that can find metaphors in the words and makes the characters come alive. And, as a writer, Ben has the most important aspect, which is the willingness to stick to the story and to push it.”

Not surprisingly, Busch has made “true, brutal honesty” his push with Ramadi, which draws upon his own harrowing experiences in the city. “It’s a picture of the occupation that’s honest in a way we haven’t seen yet: honest to the place,” says Busch. “Iraqi culture has many influences. And our oversimplifications about it have betrayed its subtleties.”

“I feel a deep, profound need to revisit that,” he says, speaking at once as artist and as Marine. “I don’t really know how to describe ‘duty,’ I just believe in it.”

— Alex Bhattacharji ’92

Alex Bhattacharji ’92 is the articles editor of Details magazine. His work has also appeared in Rolling Stone, Men’s Journal, and Saveur.

Photos: Benjamin Busch ’91 in Iraq, April 2003, during a dust storm. Photography by Sergeant James Letsky, USMCR. Photos of Busch as Major Todd Eckloff, Paul Schiraldi, HBO. Photos in Iraq, Benjamin Busch.

Have a comment about this article? Email vq@vassar.edu.