The Trouble with Jane Austen

When asked what I teach at Vassar, I sometimes jokingly reply “Jane Austen.” My real field of expertise is the Victorian novel, and Jane Austen is not, as I routinely remind my students, a Victorian novelist. She died twenty years before Victoria ascended the British throne, and as a novelist she shares more in common with late eighteenth-century writers like Ann Radcliffe and Fanny Burney than she does with her Victorian successors. Austen belongs to the same generation as the early romantic poets, and the French Revolution — rather than the industrial revolution — was the most salient historical feature of her short life. Nonetheless, Austen’s currency is such that I spend a lot of time teaching her novels.

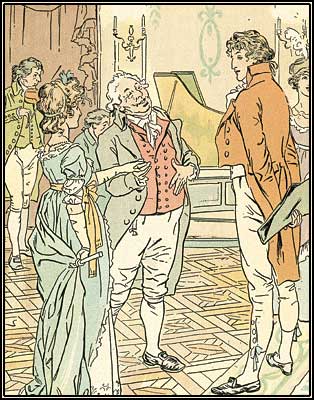

“‘Mr. Darcy, you must allow me to present this

young lady to you as a very desirable partner.’”

While fueled by the popularity of the film adaptations, this surge of enthusiasm for all things Austen extends beyond it. A variety of explanations routinely circulates within English departments to account for the baffling hold Austen exerts over the iPod generation: nostalgia for what seems to be a gentler and more genteel era (a nostalgia sustained by Austen’s habit of keeping the servants out of sight); latent American Anglophilia that rises and falls with the fortunes of Masterpiece Theatre; the surprising pleasure found in the supreme chastity of Austen’s romances. All of these are plausible, although I would add one more: I suspect that the young men and women I teach at Vassar, who have freedoms that Austen would have found bewildering, discover some distant echo of themselves in Austen’s stories. The pressure to be accomplished and high-achieving — to live up to their own (and their parents’) expectations — may at times feel as suffocating as the propriety that envelops and restrains Austen’s characters.

For a teacher, Austen’s popularity generates its own paradox: it makes her novels easy to teach, but difficult to teach well. To begin with, her famously ironic narrative voice is unnerving. Nothing is straightforward in an Austen narrative, which more often than not says one thing and means another. So, for example, Austen begins Pride and Prejudice, a novel about genteel female poverty, by declaring “that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” Single men of good fortune want for nothing in Pride and Prejudice. It is the Bennett sisters, done in by an entail that leaves the family property to a distant male cousin, who are in “want”; but female needs and desire, Austen’s irony here exposes, often go unnoticed in her society. And then there is her cultural distance from us. For all their readability (and Austen’s effortlessly elegant prose style is uncluttered by the later Victorian penchant for thick description), her novels offer only a deceptive accessibility: the world Austen represents, so domestic at heart, seems to resemble ours, and thus we think we understand the characters’ motives and actions. Austen is our contemporary but also as distant from us as Shakespeare or Milton. So when a character in an Austen novel walks into a room and starts speaking, we understand the words — there’s no tricky Early Modern English to gloss — but not always the layers of meaning compressed into those words.

No act of translation seems necessary for novels so relentlessly focused on courtship and marriage. For many readers, Austen’s keen observations on domestic relations have the force of universal truths, which transcend the need for any fussy literary-critical contextualization. Happily depicting life as a whirl of sociability, of tea-drinking and quadrille-dancing, Austen — so this view of her goes — did not concern herself with the political events of the day: if the militia shows up in town, surely it must be to provide officers with whom her heroines can dance, not to protect the nation from Napoleon’s armies. Of course, Austen’s own self-deprecating comments on her art (she once compared her novels to miniatures — “the little bit…of ivory on which I work with so fine a brush”) do nothing to dispel this vision of her as indifferent to the world beyond the drawing room.

However, while Austen may seem to write about trivial matters (dresses, balls, and morning calls), she is really a sociologist and a historian, anatomizing the social and economic arrangements of her day. Her novels are topical, acute records of the pressures being put on traditional forms of power by emergent forms of wealth. At the turn of the nineteenth century, the large landowners who ruled Britain through patronage and paternalism were visibly being challenged by democratizing forces. Austen’s novels chart the social reconfigurations that occur as old and new money, old and new forms of power, old and new values come into contact and conflict with each other. Her novels delight in skewering the pretensions of the nouveau riche and the ancien régime as well as the tensions between them. Moreover, Austen herself was not an impartial observer of these transformations but participated in them: born into the minor gentry (her father was a clergyman), she carefully kept track of every penny her novels earned in the literary marketplace.

“Mr. Denny entreated permission to introduce his friend, Mr. Wickham.”

Indeed, one of the first things I ask my students to do when reading Austen is to note her novels’ scrupulous accounting: she almost always identifies not only the amount but also the source of the characters’ income. For example, the plot of Pride and Prejudice, her best-known novel, balances on the social and economic distinctions between Darcy and Bingley. Darcy’s ten thousand a year comes from an immense landed estate, and while not titled himself, the family has aristocratic connections (his uncle is an earl). In contrast, Bingley’s father made a fortune in trade, but died before he could purchase the estate that would begin the family’s rise into the landed gentry. Bingley’s deference to Darcy in matters great and small (including his choice of a spouse) must be placed in the context of Bingley’s social position. With a tenuous hold on gentility, Bingley’s complaisance and lack of self-assurance arise from a social insecurity, as does his sisters’ hauteur, which is merely the flip side of his excessive courtesy. Desperate to gentrify the family through marital alliances, the Bingley sisters become monsters of pride and conceit as they magnify every social indiscretion committed by the Bennets in order to separate their brother from Jane Bennet, whose vulgar relatives threaten to exert a downward pull on the Bingleys’ upward trajectory. England’s fluid social hierarchy allowed families like the Bingleys to become, within a generation or two, members of the landed gentry, and the human costs of this mobility — the way it formed and deformed character — fascinated Austen. Foregrounding money and status always leads students to a greater understanding of Austen’s achievement as a realist: that her realism is grounded in her perception that personality structures are determined by and through social relations.

To restore Austen to her historical context entails an act of estrangement because students — attracted by Austen’s irony and wit — want to claim her as a modern writer, one of their own tricked out in muslin and lace. I often begin this process of estrangement by turning first to Virginia Woolf, whose seminal work of feminist literary criticism, A Room of One’s Own, situates Austen at the center of a distinctive female literary tradition. For Woolf, Austen is the answer to the age-old question of why no woman ever wrote (the equivalent of) the plays of Shakespeare: because she wrote the novels of Austen instead. The genius of both, Woolf contends, resides in their shared capacity to transcend all impediments and write “without hate, without bitterness, without fear, without protest, preaching.” But for all the praise Woolf lavishes on Austen in A Room of One’s Own, it is an earlier, shorter essay on Austen that I find more telling. While acknowledging Austen’s focus on “the trivialities of day-to-day existence,” Woolf also notes that “Sometimes it seems as if her creatures were born merely to give Jane Austen the supreme delight of slicing their heads off.” Extending Woolf’s image of the novelist-as-guillotine, I ask my students to see Austen not merely as the purveyor of frothy romantic comedies but also as threatening, challenging, dangerous. This can be accomplished by putting pressure on a single word, like “condescension.” Nothing in Pride and Prejudice evokes a stronger visceral response from students than moments of condescension. Snobbery trumps seduction in the students’ hierarchy of moral outrages, and thus even Wickham’s rakish behavior (he elopes with the sixteen-year-old Lydia Bennet) barely registers. However, they are incensed by Lady Catherine de Bourgh’s condescending treatment of Elizabeth Bennet. I remind them that “condescension,” in the hierarchical society of eighteenth-century England, still retained a positive valence because condescending to take notice of one’s inferiors was an aspect of noblesse oblige. Given the older meaning of the word, one could read Lady Catherine’s intrusive questioning of Elizabeth as a kind of gracious, aristocratic stooping. Moreover, the interest of a great personage like Lady Catherine could be invaluable: patronage (not merit) led to advancement in traditional careers like the church or the military. By our lights, Lady Catherine is meddlesome and patronizing, and Lizzie’s spirited responses are an assertion of self-worth, indicating an admirable refusal to be condescended to. By Austen’s lights, however, the scene may be more complicated — revealing on Lizzie’s part both a strain of heroic individualism and a reckless disregard for the social arrangements of the day that aligns her — uncomfortably so — with her unmannerly and nearly disgraced sister Lydia.

Austen’s distance from us also becomes strikingly visible during class discussion of the marriage plots at the center of Pride and Prejudice. When Charlotte Lucas announces her upcoming marriage to the odious Mr. Collins, whom Lizzie has rejected only pages before, Charlotte defends her choice: “I am not romantic, you know. I never was. I ask only a comfortable home; and considering Mr. Collins’s character, connections, and situation in life, I am convinced that my chance of happiness with him is as fair, as most people can boast on entering the marriage state.” Lizzie, however, is a romantic and thus incapable of conceiving that Charlotte could be happy with the hapless Collins. Indeed, so horrified by Charlotte’s choice is Lizzie that their conversation ends awkwardly, with Lizzie privately lamenting her friend’s alliance as humiliating and disgraceful.

When I discuss this exchange with students, they invariably side with Lizzie. How could they not? Like Lizzie, they too are romantic. Over the course of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Lizzie’s belief that marriage should be compacted for the personal happiness of individuals (what historians refer to as companionate marriages) replaced Charlotte’s more material view of marriage as forming a social and economic unit rather than an affective bond. Nearly two hundred years after the novel’s publication, the companionate marriage is such a cultural dictate that nothing rattles a class more than asking if Charlotte Lucas might not be right, at least in the context of the novel. After all, the marriages represented in the novel provide some evidence that Lizzie’s starry-eyed vision of romantic love might not lead to long-term happiness. Surely her parents’ imprudent marriage, one formed from a spark of “real affection” quickly extinguished, is a case in point, as is Lydia’s foolish alliance with Wickham. To be sure, Lizzie and Darcy’s fairy-tale ending would seem to lay to rest this speculation about Austen’s investment in the idea of romance, but their happiness must be set alongside of the surprising fact that Charlotte Lucas also appears quite content as Mr. Collins’s wife.

Pride and Prejudice may be the pattern book for modern romances, but at the same time it evidences a degree of skepticism about romantic love. Austen simultaneously embraces and interrogates the ideology of romance because her novel is a testing ground, in which she submits to serious scrutiny the hypothesis that a love match is more likely to engender female happiness than a marriage of convenience. Of course, given the importance of marriage to the impoverished gentlewomen who populate her novels, skepticism about romance may have been a defensive posture. Surely there were not enough Darcys in all of Regency England to save every deserving young woman from the likes of a Mr. Collins. Supported by male relatives her entire life, the unmarried Austen would certainly have understood and sympathized with Charlotte’s contention that marriage for “well-educated young women of small fortune…however uncertain of giving happiness, must be their pleasantest preservative from want.”

Ultimately, the point of raising such issues in the undergraduate classroom is not to come to some definitive conclusion about them, but rather to put doubt in the students’ minds about the Austen they think they knew, to suggest that Austen may not be a wholehearted romantic and that her novels may in fact be more flinty and clear-eyed than is usually thought. To their credit, my students embrace this tough-minded Austen with enthusiasm, and they discover the great pleasure to be had in wrestling with the complexities of reading, writing, and thinking about Austen. Living on the cusp of the modern world, Austen was not fully of it, and her value to us may be not the degree to which she confirms our deepest beliefs, but the degree to which she troubles them.

— Susan Zlotnick

Susan Zlotnick has taught in the English Department at Vassar since 1989. A specialist in the Victorian novel, she teaches courses in nineteenth-century British literature, and she is also an active member of the Women’s Studies Program and the Victorian Studies Program. She will be spending the 2008–09 academic year on exchange at the University of Exeter, UK.

Image credit: Illustrations by C.E. and H.M. Brock, from the 1906 Frank S. Holby edition of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice