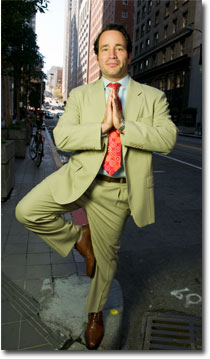

The Importance of Earning Interest: Ben Mangan '92

When Ben Mangan was a senior at Vassar, he lived in the Town Houses with four fiercely independent, strong-willed friends (one of whom, full disclosure, is authoring this profile). From day one it was clear that Ben was going to be the force for peacekeeping, the pillar of dignity around which his housemates circled, in near-constant negotiations over the just distribution of deli meats. His distinctive confluence of personality traits — including an unusual mix of wild abandon and an almost anachronistic earnestness — was the saving grace of TH E-10, class of 1992.

I met Ben when we were freshmen, though, long before we nearly came to blows over roast beef, and that earnest quality struck me immediately. I always had the sense that somehow, amidst so many of our privileged and even jaded peers who had arrived in Poughkeepsie as a matter of course, Ben was there to squeeze every atom of meaning out of the experience, in every possible manner. In all his passionate pursuits—race relations to cooking, social justice to rugby—he never did anything halfway.

More than twenty years later, it is safe to say that Ben has kept squeezing every drop out of every experience, in ways that reverberate far beyond his immediate sphere of home and work. Today he is the president, CEO, and cofounder of Earned Assets Resource Network (EARN), a San Francisco-based nonprofit organization that, through “money-management training, access to financial services, and 401k-like matched accounts,” helps low-wage workers lift themselves up out of poverty. As such, he is able to put his passion to work for the benefit of thousands of grateful families — people who, like Ben, are willing to work for what they want and understand the incomparable value of doing so.

The so-called ivory tower was not a familiar place for Ben when he arrived at Vassar in the fall of 1988 from a gritty, working-class Brooklyn neighborhood that had little in common with many of his classmates’ notions of renovated brownstones with marble mantles and fountains in the garden yard. In fact, although Ben was a top student throughout high school, spurred on by his determined mother, it is something of a miracle that he ended up at Vassar at all.

Until an older friend from his high school enrolled at Vassar and came back raving about it, Ben had planned on applying only to more affordable state schools. But when he heard his friend wax rhapsodic about the premium placed on intellectual discourse and ideas, the dynamism, and the focus on social justice at this exclusive private college, Ben decided to throw his hat into the ring, hoping the admissions office would deem him worthy of receiving aid. “It was not cool to be smart at my high school,” Ben explains. “The way my friend talked about Vassar seemed different.”

Discouraged by the inequalities in the school he worked in, where the children of wealthy families were favored and the children of poorer families ignored, Ben decided to take his newfound ideas about education back home. He accepted a position in Vassar’s admissions office, traveling the country and explaining to high-school students just why Vassar could change their lives.

It was on this job that Ben learned one of the most significant lessons of his career. His regions were New York City (all boroughs except Manhattan), northern California and the Pacific Northwest, and states such as Idaho, Montana, and Nebraska, which historically have sent few students to Vassar.

Ben had always been interested in Native American history. He convinced the dean of admissions to let him visit Indian schools in his region, making a case that in spite of its new multicultural center, Vassar was woefully underrepresented by Native Americans. “I knew firsthand that there were schools that never got a visit from Vassar, kids who had never heard of Vassar. I wanted to change that,” he explains.

But at the second school he visited, after noticing the flat reactions he was getting from students, a guidance counselor pulled him aside and said, “You seem like a nice guy, so I’m going to lay this on you straight. It’s offensive to me that you’re here — just another white person trying to get these Indian kids to go 3,000 miles away where there will be no community for them, leave them high and dry. It would be unthinkable for me to advise anybody from here to do that.”

Ben was chagrined, but emerged wiser — and all the more determined to find a way to work for justice from the inside, using his life experience and personal values to change people’s lives from the bottom up. He took the experience as “a powerful touchstone for how ideology can trump pragmatism,” and wrote about it in his application essays for graduate school. He soon found himself at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, again surrounded by people who had never known what it was to have no safety net, no reserves.

“I knew at Vassar that I wanted to do something that mattered, that was different and would create opportunities for people, but the idea really came together in grad school,” says Ben. “I had thought I would focus on education but instead studied economic development, real estate, and finance — on some level I knew I needed hard skills. I realized this was yet another situation where I didn’t know what I didn’t know.” But whatever those unknown unknowns were, Ben says, he knew he needed them “if I was to move forward.”

After a post-grad school stint as a management consultant at Ernst and Young in Chicago, Ben felt an increasing desire to go west. He had always viewed California’s Bay Area as a place for dreamers, so he took a job at a dot-com, but his heart wasn’t in it. When he received an email from a friend about a group of people who wanted to do something different to create prosperity for the working poor, it was as though the stars had finally aligned.

This project, which was to become EARN, was the work Ben had been preparing himself for, on some level, all his life. He got in touch with the organizers, prominent leaders in San Francisco’s business world and nonprofit sector, and told them he wanted to run their company. “I was 30, had no connections in San Francisco, so I tried to make it clear that this was a match on a values level. I told them this issue was personal for me, explained that I had lived in public housing, been on welfare when I was a kid.” He got the job.

Today EARN has served thousands of families. The organization’s core work is matching people’s savings so they can buy their first home, get an education, or start a small business — in short, acquire assets. Being a part of EARN requires sacrifice and determination, deferring prosperity, to a certain extent, for the next generation. EARN’s success hinges on the belief that what predicts economic prosperity is the presence of assets in a household beyond or other than a savings account. As Ben puts it, “Do your parents have a college education? Is your home owned? Has your family created wealth?”

And EARN is changing lives, one family at a time. The state of California agrees; it has replicated EARN’s plan to get “unbanked” citizens—people without any kind of bank account—into the financial system. So has Bill Clinton’s foundation. EARN is rooted in the notion of microfinance — that for a small amount of money you can bring people into the financial mainstream and have a huge impact on the people you help. It’s a way of shifting the landscape for the children in a household who would otherwise never have such opportunity.

The facts speak for themselves. EARN now has 2,500 matched accounts, making it one of the two largest individual development account (IDA) programs in the nation, along with Opportunity Fund in San Jose. More than 200 people have saved the maximum allowed in their IDAs. EARN was the 2005 winner of the Fast Company Magazine/Monitor Group Social Capitalist of the Year Award, and was named one of ten finalists in the 2005 Amazon.com Nonprofit Innovation Award.

The current economic crisis is taking its toll on EARN, but Ben is optimistic. “Sure, the people we serve are the most vulnerable to job loss or reduced work hours, but the silver lining is that folks who need money-management training, people who have worked with us or have accounts with us, are better able to weather this distress,” he says. EARN has helped over a hundred families buy their own homes, with only two defaults — and in both cases, because of foreclosure due to job loss, not subprime financing. The organization is seeing a decline in donations, but Ben says he’s tackling that problem head-on — in spite of a recent lack of sleep.

Just this spring, he and his wife, Wileen Chang, welcomed their firstborn: Alex Rafael Mangan Chang. Ben has thought a great deal about what his son means in the continuum of his family history, and it is impossible not to contemplate how fatherhood will influence his life’s work. “I think about how hard people in my life worked to position me to succeed,” he says, “and I feel like I have a new challenge, ensuring that Alex is never complacent about the things he will have that I did not.”

I have known Ben now for over twenty years. I have seen him whip up a mean stir-fry, look imposing in a pin-striped suit or wild-eyed in a rugby scrum, get fired up about a controversial novel—but I have never seen him complacent. I think I speak for all of TH E-10 at the very least when I say I can’t wait to see how Alex, like his father, takes on the world, one hard-fought victory at a time.

—Amy Wilensky ’92 is a writer whose most recent book is The Weight of It. She lives in New York City with her husband, Ben Hohn ’92, and their daughters Lily, 5, and Annika, 1.

Photo Credits: Alain McLaughlin

Have comments about this article? Email vq@vassar.edu