For School, For Country

Times of national crisis have a capacity to galvanize the citizens of towns, cities, and indeed, an entire country in support of a common goal greater than the self. That unifying force can extend to college campuses, and Vassar is no exception, especially during times of war.

Whether in support of a war effort, or against it in protest, members of the Vassar community have played integral roles in the United States’ defining military moments over the course of the last century, including a long legacy of women (and men) in the armed services, willing to risk their lives (and indeed, many have given them) to defend the country and its ideals.

World War I

Following the important role that female nurses played during the 1898 Spanish-American War, the United States Army established the Army Nurse Corps (ANC) in 1901. Julia Stimson, who graduated that year, became one of the first women—and the first Vassar graduate—to join. When the U.S. sent forces overseas three years into World War I in 1917, Stimson went, too. There she became the chief nurse of the American Red Cross (ARC) in France, and soon thereafter, joined the American Expeditionary Forces, where she rose to the level of director of Nursing Services.

Meanwhile, between 1917 and 1919, the size of the ANC ballooned from roughly 4,000 nurses to more than 21,000; of those, 111 were Vassar alumnae and some 10,000 served overseas under the leadership of Stimson. Three Vassar alumnae gave their lives, including Amabel Roberts ’13, the first ARC nurse to die overseas. As the war drew to a close, Stimson was named superintendent of the ANC and the U.S. government awarded her the Distinguished Service Medal. She remained in the Army until her retirement in 1937.

World War II

It’s commonly known that Vassar played a number of important roles during World War II, including sending many women into the Navy’s WAVES program (Women Accept-ed for Volunteer Emergency Service). But one of the college’s most critical roles has also remained its least well-known. During the war, Vassar offered a secret cryptography course, the details of which remained classified for decades. The graduates of that course—Vassar women recruited for their math and language skills—played a crucial role in the Allied success in cracking Nazi codes.

According to National Security Administration documents, women were sought for “sit-down desk jobs,” in order to relieve men from their non-combat duties so the men could go overseas to fight the war. Cryptography—the science and practice of analyzing and deciphering codes—was considered the most important of these jobs. And while women needed stellar math and language skills, the highest value was placed on a woman’s integrity, because of the highly classified nature of the work.

In 1942, Navy officials approached Dean C. Mildred Thompson about starting a covert elective course at the college. The cryptography training was subsequently offered at Vassar between 1943 and 1945. (It was also offered at select other women’s colleges, such as Goucher, as well as many of the Seven Sisters—Smith, Bryn Mawr, Mount Holyoke, Radcliffe, and Wellesley—which proved fertile recruiting ground for Navy brass looking for women with the right stuff.)

For years, details of the Vassar class were sketchy at best. One source suggested that math professor Mary Evelyn Wells taught a class that included anywhere from 10 to 50 women. The late Rowena Emery Rogers ’43—who took the class, but didn’t finish it for personal reasons—recalled that the class was given on Monday nights in the Students’ Building, taught by Navy personnel. She estimated that 30 women took the course.

But in an interview from late 2010, Cornelia Newlin Borgerhoff ’43—one of the last surviving graduates of the course—paints a different picture. She remembers being recruited by the Navy, but says the secret course didn’t meet as an official “class.” “It was done on an individual basis,” she says. “We took the course quietly, and didn’t talk to anyone else about what we were doing.” Homework included “puzzles,” essentially Nazi communications written in code, on which the young women worked.

After graduation, Borgerhoff served in naval communications in Washington, DC, translating intercepted messages from German submarines in the Atlantic. But wider recognition for the important work that she and other Vassar cryptographers were doing didn’t come until much later (her husband didn’t even know the specifics of her job), when the details of their work were finally declassified.

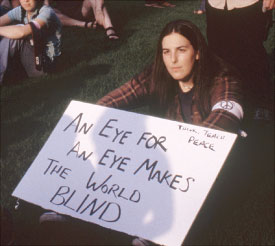

Vietnam

No war may have divided the country—and the Vassar campus—more than that of Vietnam. Though American involvement in the Vietnam conflict spanned several decades, the 1960s were by far the most active period on Vassar campus, coinciding with the steadily increasing U.S. military involvement.

In 1961, the same year that U.S. troop levels tripled in Vietnam, Vassar students participated in a “Student Turn Towards Peace” demonstration in Washington, DC. They picketed the White House, held a peace march, and met with government leaders, calling for disarmament, an alternative to the Cold War arms race, and a halt to atmospheric nuclear testing.

One year later, when U.S. troop levels in Vietnam tripled for a second time, Vassar students and faculty protested in Poughkeepsie. A peace vigil was held, arranged in part by the Vassar for Peace Committee. That same year, participants in the Walk for Peace—which traveled from New Hampshire to Washington, DC—made a stop in Poughkeepsie to attend a public meeting held at Vassar.

The watershed year for Vassar’s anti-war activism proved to be 1965, when ground combat units were first deployed in Vietnam and the U.S. launched a sustained bombing mission known as Operation Rolling Thunder. Vassar students marched in Washington, DC, in a protest against U.S. involvement in Vietnam. It was just the beginning.

By 1966, Vietnam was a hot-button issue on campus, and students and faculty formed an ad hoc committee to hold a teach-in, titled “Vietnam: An Analysis of the Issues.” Then, in 1967, 200 faculty and students marched in front of Main in silent protest against the war.

When the Tet Offensive began in 1968, it pushed Vassar’s campus community to respond with greater urgency and force of will. In 1969, more than 150 faculty and more than 1,000 students signed an anti-Vietnam War petition and delivered it to college president Alan Simpson. On October 15—a national day of protest against U.S. involvement in Vietnam—President Simpson authorized faculty to cancel classes.

Not content to restrict war protests to the campus, in 1970 some 130 students, faculty and administration—including President Simpson—traveled to Washington, DC, to directly lobby against the war.

By the early 1970s, campus protest at last quieted down, partly in sync with the de-escalation of U.S. involvement, and eventually, the end of the war.

September 11

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, hit close to home for Vassar, both literally and figuratively. Two Vassar alums—Ruth Ketler ’80 and John Schwartz ’75—died in the New York City attacks.

Within hours of the planes hitting the Twin Towers, the Alumnae & Alumni of Vassar College website featured a “check in” message board where people could post notices that they were okay, or could inquire about missing family and friends. (It remained on the website as a de facto memorial until 2005, when a new site was designed.)

Also within hours, a big-screen television and phone banks were set up in the Villard Room. One day later, President Fergusson held a community gathering on the library lawn, during which students, faculty, and staff sang dona nobis pacem (give us peace). The campus chapel remained open 24 hours a day, and the Counseling Service extended office hours and held seminars on dealing with grief.

In the following days and weeks, the college created a September 11th Task Force (later resulting in the planting of a peace garden near the Students' Building). Students came together, too, organizing a fund drive for the American Red Cross and gathering supplies for rescue workers.

Four years later, Vivek Mahapatra ’05, class president, described it as the defining moment for the Class of 2005’s time at Vassar in his remarks at commencement.

Gulf/Iraq/Afghanistan Wars

In more recent years, Vassar’s legacy of military service has continued, embodied by such alumnae/i as Benjamin Busch ’91. After accepting a commission in the Marine Corps following graduation, Busch shipped off for the second Gulf War, where he served two tours of duty in Iraq (once as a Marine and once as a Marine Reservist) and received the Bronze Star.

Evan Wright ’87 was embedded with the Marine Corp’s First Reconnaissance Battalion (whose motto is “Swift. Silent. Deadly.”) for a series of articles that appeared in Rolling Stone. (The series was later expanded and became Generation Kill, a best-selling book turned HBO series.) Publishers Weekly noted Wright’s “evocative, accurate war reporting.”

As with earlier wars, Vassar’s extended community did not come away unscathed. Robb Rolfing ’00—an astronomy major and star on Vassar’s men’s soccer and lacrosse teams—enlisted in the Army following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. A Green Beret, staff sergeant, and special forces engineer with Bravo Company, 2nd Battalion, 10th Special Forces Group (Airborne), he was killed in action in Baghdad in 2007, during his second deployment to Iraq.

A Focus on Peace

Vietnam wasn’t the first or the last time Vassar students took a vocal stand for peace.

In September 1931, Vassar was one of three U.S. colleges to receive the World Peace Medal from the Federation Interalliee des Anciens Combattants (Interallied Federation of Veterans)—a worldwide organization of WWI vets. Two years later, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom met at Vassar.

Meanwhile, however, militant changes were afoot on the world stage: Hitler and the Nazis were on the rise to power in Germany, Mao Zedong was ascending the military and political ranks in China, and the Soviets and Japanese were setting their sights on military offensives.

Consequently, in 1936, roughly 900 Vassar students and faculty members met at the Students’ Building to participate in a worldwide “peace strike.” One year later, the Vassar Peace Council sponsored a peace conference at Vassar, “All Youth against All War.” And in 1939, the college observed Peace Day with a college assembly in the Students’ Building.

More than 60 years later, Vassar students were at it again—several students were among the founders of the Campus Anti-War Network, considered the largest grassroots campaign of its kind in the country. The proximate cause for its founding was the war in Iraq, though the group has taken up other causes as well.