Vassar Fashion

This article has been updated.

“Fashion is, as has been said a thousand times (but not by me), a tumultuous jade, given to many aberrations,” noted Lois Long ’22, in a September 1950 issue of the New Yorker, where she wrote a regular column of fashion criticism, “Feminine Fashions,” in the magazine’s On and Off the Avenue section.

During the earliest days of the college, in the late 1860s, Hannah Lyman, Vassar’s notoriously conservative first Lady Principal, dictated campus fashion. Her strict dress code, often espoused in letters sent home to students’ parents, was precautionary, lest the college become “a hot bed for extravagance in dress.” She “required” only four dresses for students—two for the mornings while in class, one for the afternoon and the evening meal, and one for Sundays and special occasions.

Dress to Un-impress

Vassar’s all-female (and very intellectual) leanings made for more than understated fashion sensibilities during the first decades of the 20th century. Marion Willard Everett ’14, writing in a letter home during May 1911, noted that “… on the whole, the girls [at Smith] are better dressed, but that’s because there is a continual stream of men there. Here where a man is a curiosity we are rather slovenly I’m afraid. I’d hardly know some of the girls when they get ready to go home.”

A Self-Critical Sensibility

Julia Coburn Antolini ’18 wasn’t convinced that Vassar’s smart women and the all-female status of the college precluded students from making at least a small effort in the fashion department. Writing in 1937, she opined: “Look at a group of ‘college women’ gathered together, for an alumnae or college club meeting. The average level of intelligence is probably high in comparison with any other group of women. But the level of clothes sense and taste is low. … Is there a type of dress that indicates brains, and so sets one off from the rest of the population and absolves one from attention to attractiveness, grooming, and other standards?”

The Iconic Era

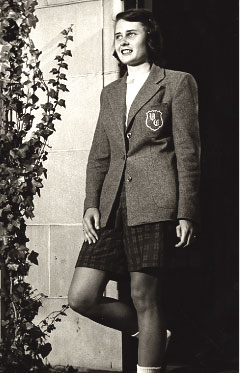

By the 1950s, Vassar fashion had undergone a remarkable transformation. Vassar was suddenly the “it” scene for what young women should be wearing. It epitomized for women’s collegiate fashion what Princeton had become for the men’s Ivy League “look.” Soon, the now-iconic image of the “Vassar girl” had settled in the minds of the American public and the media, where magazines such as Vogue and Life published elaborate photographic spreads dedicated to documenting the refined fashion sense of Vassar’s young women.

What was the look? Cashmere twin sweater sets. Bermuda shorts (often paired with knee socks and saddle shoes). Tweed blazers. Christian Dior dresses. And surprisingly enough, men’s collared button-down dress shirts, preferably from Brooks Brothers, and preferably previously worn by a father, brother, or boyfriend.

The Side Unseen

The “Vassar girl” captured in the pages of Vogue was one thing, but there was quite another face to campus fashion. The iconic images of the 1950s were the public side of Vassar fashion, when young women got dressed up for weekend events or mixers with men’s colleges. Day-to-day, in the relative privacy of their all-female life on campus, things were decidedly more casual. In particular, denim took on a growing popularity, though magazines were reluctant to document this trend.

Unlike other Seven Sisters colleges, Vassar was largely free of prescribed fashion “uniforms” or standards of dress. The result was a liberal fashion environment that allowed—and perhaps even encouraged—experimentation and fashion freedom. That trajectory continues to this day, when one would be hard pressed to pigeonhole campus-wide Vassar fashion into any one “look,” description, or formula.

Update: Rebecca C. Tuite, who attended Vassar as an exchange student from the University of Exeter, UK, in 2006 and 2007, has been working on a manuscript for a book titled “Vassar Style: Fashion, Feminism and the 1950s American Media.” Her material and research support was very helpful in the preparation of the article “Vassar Fashion” in the Sesquicentennial issue of the Vassar Quarterly, especially in regard to the section titled “The Iconic Era.” We failed to properly acknowledge Ms. Tuite and her work as sources for the article. We wish to apologize for this omission and thank her for her generous assistance.