A Woman’s Place

The college’s progressive agenda of higher education for women has been well-established. It is a hallmark of Matthew Vassar’s great enterprise. And yet, even at the founding of the college, his forward-thinking stance on women’s education was framed within societal expectations of a woman’s place and role.

In his February 26, 1861, communication with the college’s new Board of Trustees, the founder expressed a desire for Vassar’s young women to study “Domestic Economy, practically taught, so far as is possible, in order to prepare the graduates readily to become skillful housekeepers,” in addition to the many standard liberal arts and science courses that were to be studied.

To modern ears, it is a curious juxtaposition, that women highly educated at a college such as Vassar would then be expected to become skillful housekeepers in the home, as opposed to using their intellect and education to pursue a career.

By 1865, with the first women officially on campus and taking classes, Matthew Vassar’s perspective had broadened. In his April 13, 1865, correspondence with Vassar’s Trustees, he noted: “It is my wish now … to build an institution for the culture of women in the highest character—an institution where women may be instructed in all the branches of literature and science suited to the sphere assigned them in social, moral, and religious life, and for preparation for the successful pursuit of every vocation wherein they can be made useful for their own maintenance, and for the good of society and the race—an institution, too, where, in due time, women shall be the teachers and educators of women.” Perhaps most importantly, he added, “I am pleased to observe that, since the inauguration of our enterprise in 1861, great changes have taken place in the public mind regarding what may be appropriately considered the sphere of woman.”

Indeed, an article about one of Vassar’s first commencements in the June 28, 1866, edition of the New York Times seemed to bear this out. “If … there be a solitary subscriber to the Times who doesn’t believe with his whole heart in the doctrine of liberal female education, he ought to be ashamed of himself,” the reporter wrote.

However, Matthew Vassar’s and the Times reporter’s sentiments hadn’t necessarily taken root in the public mindset. Throughout the early 1870s, newspaper reports made frequent references to “wild women,” a derogatory term associated with women’s suffrage, education, and independence, which all went hand-in-hand with defining a Vassar woman. The college, it seemed, was progressive enough to not just push a women’s rights agenda, inspire conversation, and drive social change, but also to prompt backlash.

A June 1, 1873, New York Times editorial on women’s access to higher education was highly critical of the idea in general, and of Vassar College in particular. “We firmly believe that female education in this country should be better than it has been, but that there should be less of it,” the writer mused. “We should improve the quality and diminish the quantity.” With regard to Vassar especially, “The steps taken in opening a wider sphere of education for women … by the foundation of such colleges as Vassar … have our heartiest sympathy and approval. Still, all these schemes of training include too much in a short time, and, despite the disclaimer of its President, we have strong reason for believing that Vassar College has erred in this direction. What the girls of the middle and upper classes need is a slow, thorough, healthful, and masculine course of studies.” Most tellingly, the editorial concludes with a broader statement about society’s expectations for women: “One can fancy what sort of young ladies would come forth from a four years’ university course, when they had struggled with, day by day, and often surpassed the best minds among the young men of the country. They certainly would not be the ideals which the world had formed till now, of the most refined womanhood.”

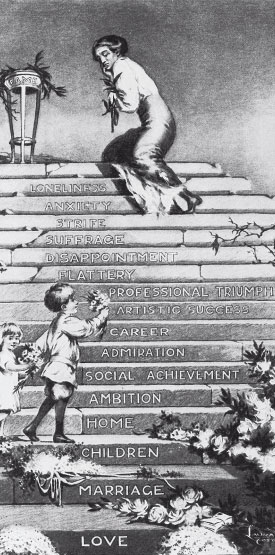

The passage of 20 years of time offered an opportunity to see exactly what kind of women Vassar was turning out, and how they were fitting into society (or not). On November 1, 1893, the Los Angeles Times published “College Girls and Marriage: Something Wrong with Higher Education, as Half Become Old Maids,” a detailed examination of the history of Vassar graduates. It looked at Vassar’s first 24 graduating classes, which totaled 867 women. Roughly one third were married. A similar number had become teachers, and their ranks also included physicians, writers, artists, bookkeepers, and a handful of farmers. “The main point,” wrote the reporter, “is whether or not the college girl is less available for matrimony on account of her distinguished attainments.”

Sources said, yes. “Only 36 per cent of marriages reported among graduates of Vassar is not a record of which that institution has reason to be proud,” the editorial continued. Allowing for the possibility that some Vassar women might simply marry later in life, the writer admitted that up to 50 percent of Vassar women might eventually tie the knot. Even so, that wasn’t enough. “If no more than half marry, there is certainly something wrong with the curriculum. The world would become uninhabitable if only 50 percent of the women in it married, leaving an equal percentage of men unprovided for.”

Apart from Vassar women’s rate of marriage, there was also a question as to the quality of those marriages. “It is said that if Vassar girls marry later, they marry better than girls who are not college-bred. This is open to very serious question, which may finally turn on what is meant by ‘better,’” the reporter wrote. “It does not appear that the husbands of Vassar girls have ever figured extensively among the great men of the world, the patriots, statesmen, scientists and philanthropists, whose work has been a blessing to mankind. It is certainly true that the husbands of women not educated at Vassar have been represented extensively in that class.” Were Vassar women so accomplished that they overshadowed their spouses or did their erudition repel the “statesman” class?

Vassar’s graduates were out in the world, redefining the traditional roles of what it meant to be a woman in society. An anonymous female writer saw it happening and elaborated eloquently in a June 27, 1889, article for the New York Times titled, “Vassar College: A Woman’s Impressions”: “This happy and fortunate group … have spent under such glorious auspices that transition period of life when the grand probabilities of the girl may either rise so high or sink so low, as they merge into the fixed possibilities of the woman.” Those possibilities were changing, and the “woman” was in the midst of a major makeover, driven in no small part by the efforts of Vassar’s graduates.

That makeover especially accelerated in the late 19th century and into the early decades of the 20th century, as captured by three sets of novels, each written by or based on a Vassar alumna, and each containing Vassar protagonists.

The Three Vassar Girls series, by Elizabeth Williams Champney, Class of 1869, was a window into 1880s Vassar. Ultimately a collection of 11 novels, featuring three Vassar girls who traveled the world together, the books—while also filled with lighthearted accounts of the girls attending parties and meeting boys—addressed important topics, including bigotry, career development, independence, self-sufficiency, and societal expectations. The three Vassar girls served as a model for the emerging societal roles women were championing, such as when the author makes an implicit statement about women’s independence during a scene in Three Vassar Girls Abroad when one of the three declines the assistance of a porter who’d assumed she would like him to carry her luggage.

The three Vassar girls also had a degree of self-awareness, an understanding that their behavior as “well-conducted, earnest American girls” would influence how society responded to this new kind of woman. “The reputation of America, and Vassar as well, is at stake in our insignificant persons,” one of the three said in Three Vassar Girls in England. “Only the very highest success, or a magnificent failure will satisfy them—mediocrity is the one unpardonable sin,” the narrator later noted.

That grand ambition—to great success or spectacular failure—when combined with a measured restraint, were values instilled in those young women at Vassar. “One great benefit which we received at Vassar was a development of latent energies, whose existence we never suspected, and a pruning of individual extravagances … the shy are encouraged to self-confidence … the over-bold are shamed into reticence … the meek gain spirit … the apathetic are stimulated,” one of the three noted. Vassar took girls, bound by the constraints and expectations of society, and instilled them with the skills and education they needed to go out into the world and effect change. It was a time of promise for what education (via Vassar) might empower those women to do as they defined their place in the world.

By the 1910s, such promise had turned into a more concrete hope that societal change was happening, and Vassar women were a part of it, as evidenced by Carney’s House Party by Maud Hart Lovelace, author of the popular Betsy-Tacy series. Originally published in 1949, but set in the 1910s, it followed the exploits of fictitious Vassar alumna Carney Sibley. Carney and many of the book’s other characters and details concerning Vassar were all based upon the real life experiences of Marion Willard Everett ’14. Professors Jean Charlemagne Bracq and Lucy Maynard Salmon were actual Vassar professors, and Carney’s friend, Isobel, was actually Dorothy Brinsmade Jackson ’14.

The novel showed Vassar to be a transformative place where girls became not just women, but active women. Consider that the character of Carney Sibley “had come to Vassar … wearing a mantle of complacency.” That complacency was soon transformed by the values of the institution, such that later, Carney proclaimed, “I represent Vassar on every occasion!”

Representing Vassar on every occasion meant becoming a progressive woman who pushed the boundaries of society’s expectations. When Carney’s real-life counterpart, Willard, wrote a letter home in February 1911, describing how she’d switched to wearing a less restrictive corset, she concluded: “Don’t tell the girls at home—they’ll think I’m becoming a suffragette.” Such was Vassar’s reputation, and understandably so.

Willard’s time on Vassar’s campus was immediately preceded by that of Inez Milholland ’09. A vocal suffragist, Milholland held a deep conviction to openly discuss the topic on campus, which put her at odds with then-president James Monroe Taylor. Most famously, during Willard’s junior year in 1913, Milholland organized a suffrage parade in Washington, DC, one day before President Wilson’s inauguration. During the parade she wore a crown and white cape, and rode atop a white horse.

In 1920, the 19th amendment passed, officially (and finally) granting women the right to vote. President Henry Noble MacCracken, much more progressive than his predecessor, Taylor, was then at Vassar. It was a time of continued flux for women in America. But access to women’s education and women’s right to vote were one thing. The evolution of women’s place in society (and in the home) was quite another.

No single book captured this ten-sion more than The Group, by Mary McCarthy ’33. Published in 1963, but set largely in the 1930s, it tells the tale of eight close friends—all fictional Vassar women—closely modeled after McCarthy and her contemporaries. At once a satire and a serious commentary on the place of women in society, The Group was all-encompassing in its tackling of wide-ranging issues such as money and careers, sex, contraception, divorce and extramarital affairs, breastfeeding and child-rearing, female camaraderie, the push-pull between independence and marriage, and tension with men.

The women of McCarthy’s group found themselves facing familiar problems in familiar situations faced by earlier generations of Vassar women. In a pivotal scene, Priss and Norine—two of the eight—discuss their babies and their troubled relationships. “The trouble is my brains,” Norine explained. “I was formed as an intellectual … Freddy [her husband] doesn’t mind that I can think rings around him … But I’m conscious of a yawning abyss.” That abyss proved to be her intellect and education on one side, and on the other, Freddy’s expectation that Norine also be a “Hausfrau,” a housewife who could dress well, set the table, and order around servants—the educated housewife “ideal” abandoned by Matthew Vassar in favor of a more liberated womanhood.

In the climax of the scene, Priss asked Norine, “You really feel our education was a mistake?” Priss’s own husband, a pediatrician, cer-tainly felt so, for “it had given her ideas he disagreed with.” Norine concurred. “Oh completely,” she said to Priss. “I’ve been crippled for life.”

Education and Vassar offered hope and a changed world, but in some ways, didn’t deliver, because change outside of the institution hadn’t kept pace. To the women of The Group, theirs was a fate even worse, perhaps, than not having gone to school at all. They might have stayed blissfully ignorant, and resigned themselves to their expected place in society. Instead, as educated Vassar women, they were burdened with the knowledge of what might be, but which hadn’t yet come.

In the nearly 50 years since The Group was published (and the 80 years since the fictitious events unfolded), much has changed regarding women in society, and Vassar’s women have continued to play a pivotal role in making that change happen. But while the specifics have changed, many universal themes remain—sex, money, careers and the glass ceiling (even if the ceiling is higher than it once was), relationships (both heterosexual and lesbian), childrearing, bonds between women and enduring female friendship, and being an independent, intelligent, young woman in what might still be considered a man’s world.

It’s no surprise, then, that 1996 saw the release of Candace Bushnell’s Sex and the City, a modern adaptation of McCarthy’s The Group. Just as before, the focus is on a tension between men and marriage, and a woman “being a contender in her own right,” noted the website Jezebel. Sex and the City is essentially the eight women of The Group, reconstituted as a quartet of young, smart, attractive women—some pursuing careers, others family, all navigating their way through a complex tangle of relationships and societal opportunities and constraints. They are empowered (and powerful) women, who still find themselves coming up against boundaries … even if some of those boundaries are internal rather than societal.

(Lest there be any doubt about the relationship between Sex and The Group, Virago Press tapped Sex and the City author Bushnell to pen the introduction to a 2009 re-release of The Group in England. Commissioning editor Donna Coonan noted that, for Bushnell, McCarthy’s The Group was “indeed the inspiration for her most famous novel.” In her intro to The Group, Bushnell highlights exactly what so impressed her about McCarthy’s work, and tells of how her editor at Grand Central Publishing, now part of Hachette Book Group, asked her to write “the modern-day version of The Group.” And in 2010 Bushnell published The Carrie Diaries, a prequel to Sex and the City, in which the protagonist, Carrie Bradshaw, idolizes author Mary Gordon Howard, a fictionalized homage to Mary McCarthy.)

A Fortunate Age, published by Joanna Smith Rakoff in 2009, is the latest book inspired by McCarthy’s The Group. Described by Publishers Weekly as a “nostalgic portrait of a postcollegiate group of Gen-Xers awkwardly navigating weddings, pregnancies, betrayals, and funerals in pre- and post-9/11 New York City,” it is an even more literal adaptation of The Group, whose narrative was artfully bookended by a wedding and a funeral, whose “meat” consisted of numerous pregnancies and betrayals, and whose narrative was caught in the turbulent, changing times of Depression and post-Depression, and post-WWI and pre-WWII, America.

For 150 years, it seems, Vassar and its women have been at the center of an ongoing evolution-cum-revolution. Its themes are timeless, even as the minutiae change with the times. With the advent of coeducation in the late 1960s, though, the “other” sex and the controversies surrounding their admission to the college began to take center stage.