The Growing Autism Advocacy of Zoe Gross ‘13

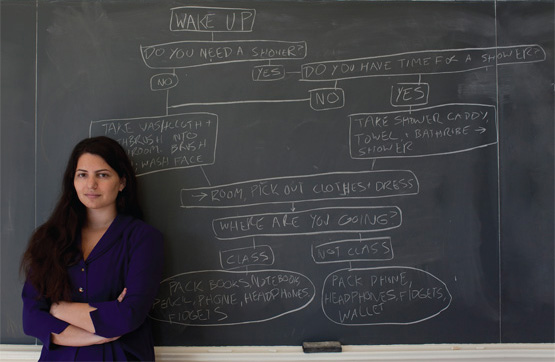

Like many college students, California native Zoe Gross ’13 has a morning routine: shower, brush teeth, get dressed, eat breakfast, go to class. But unlike her classmates, she does so with the aid of a flowchart.

The flow chart is Zoe Gross’s way of making sure that “I’ll be clean, and wearing all my clothes, and have the books I need for my first class,” she says. “At home, if I forget, one of my parents will remind me; someone makes sure you get out of bed on time, that you eat your food. At college, I have to remember to eat dinner, and no one will remind me about that.”

Why does Gross—a smart, responsible, young woman—need such reminders? She is autistic, diagnosed on the spectrum at age four.

The autism spectrum captures a broad diversity of people, and Gross’s disability manifests itself in certain ways. Organization, for example, is difficult for her, hence the flowchart. She’s also very sensitive to sensory inputs, such as background noise, and so she often wears headphones in order to help her concentrate better during breakout discussions in class or when she’s working in the college’s costume shop, where the hum of sewing machines gets pretty loud.

“I can speak with my voice. I go to college. I can do academic work,” she says, eager to bust stereotypes and myths about autism. “But I definitely have trouble with some of the expectations of what appropriate behavior is, like making eye contact, or knowing what someone is thinking without them telling you. I think pretty slowly, so it can take a while to understand a concept. I can’t do the classes at the speed everyone else can.”

When Gross first arrived at Vassar, she felt isolated. “I didn’t find other autistic people, or people with disabilities, to talk about common experiences,” she says. Gross found community online, in the writing of autistic bloggers. “For a lot of us, it’s easier to express ourselves in writing,” she says. By 2010, she had started a blog of her own, Illusion of Competence, which focuses on being an autistic college student.

Impressed with her writing and perspective, the nonprofit organization Autistic Self Advocacy Network (ASAN) invited Gross to contribute to its new Navigating College handbook. Her essay, “Better Living Through Prosthetic Brain Parts,” (by “prosthetic brain parts” she means strategies to keep her organized) led to an internship with ASAN, where Gross helped organize a December 2011 Harvard conference on the ethical, legal, and social implications of autism research. In response to the March 2012 murder of autistic 22-year-old George Hodgins by his mother, she also organized a 2012 National Day of Mourning—with vigils held in 12 different cities—to raise awareness about a little known issue: disabled victims being killed by overwhelmed caregivers.

Most recently, Gross completed a summer 2012 Washington, DC, internship with the American Association of People with Disabilities, where she worked on disability legislation in the office of Senator Tom Harkin, chair of the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions. A high point for Gross was having a meeting with President Obama.

“I came into the internship wanting to acquire political literacy,” Gross says. She walked away with more than that. “I really would like to go into advocacy as a career,” she now says. To wit, she has declared an independent major in disability studies at Vassar.

There are still many myths about autism, Gross says, and not enough autistic people in leadership positions driving advocacy and disability policy. People are aware of the autistic “poster children,” but don’t think about the fact that these children grow up to be adults, she argues, and leaders don’t look to children to be leaders and advocates on behalf of the cause. Which is why Gross has taken such a proactive role sharing her perspective and giving a voice to the autistic community. (The New York Times quoted her in the article “The Autism Wars” earlier this year.)

“The biggest myth I’d like to bust is that autism is bad,” she explains. The net effect, Gross says, is that the general public “writes off [autistic people] as less than a person.”

“What I want people to know is that autism is different,” she says. “Just as we have different races, genders, sexual orientations, abilities, and disabilities. Autism is part of human diversity and just as valuable.”