Cold Comfort: Peipei Qiu Bears Witness

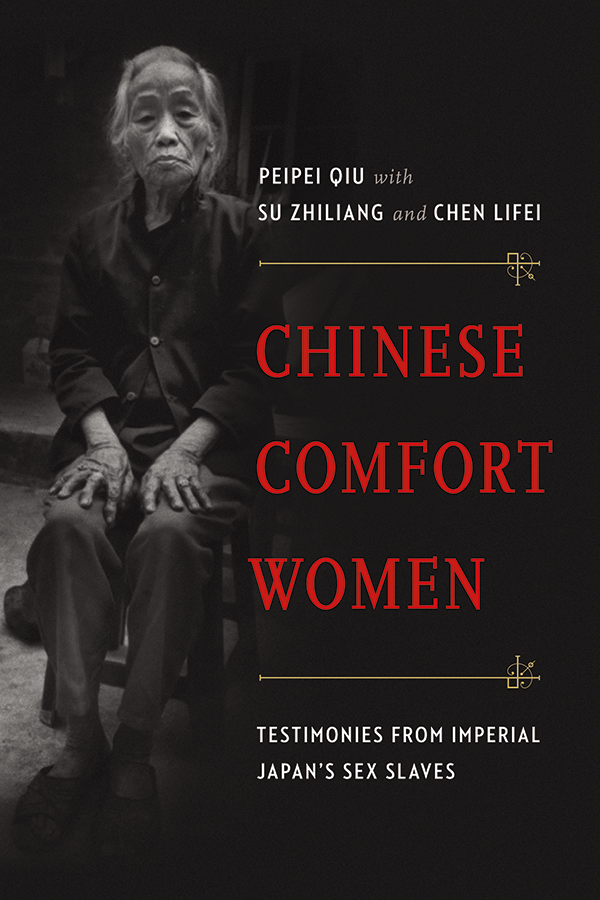

Sitting at a table in Poughkeepsie’s Babycakes Café, sipping iced tea, Peipei Qiu admits that she sometimes cried when writing her latest book. It’s easy to see why. A professor of Japanese and Chinese and director of Vassar’s Asian Studies program, Qiu is the principal author of the groundbreaking study Chinese Comfort Women: Testimonies from Imperial Japan’s Sex Slaves.

The “comfort women” system began in 1932 after the Japanese Army invaded Manchuria. An estimated 200,000 to 400,000 women were held in sexual slavery in military “comfort stations” during those war-torn years, and current research indicates that as many as half were Chinese. The system of abuse escalated after the infamous 1937 Nanjing Massacre, and continued through World War II.

Qiu’s introduction explains that the term “comfort women” was clearly a euphemism. “Those who resisted being raped were beaten or killed, and those who attempted to escape could be punished with anything from torture to decapitation,” she writes. The so-called comfort stations were placed in a range of locations—from military barracks to improvised settings in confiscated temples, sheds, cave dwellings, and the victims’ own homes.

Written in collaboration with Su Zhiliang and Chen Lifei of Shanghai Normal University, Chinese Comfort Women has garnered media attention from the Wall Street Journal, Voice of America, and others. It received a starred review from Publishers Weekly. “This vital work, combining exemplary scholarship and humanitarian activism, should prove valuable to a wide audience and indispensable to specialists,” the reviewer concludes

By her own admission, Qiu is an unlikely candidate to document this brutal history. Her first book, Bashō and the Dao: The Zhuangzi and the Transformation of Haikai (University of Hawai’i Press, 2005) hews more closely to her academic specialty, comparative studies of Japanese and Chinese literature. But in 2002, Qiu and colleague Seungsook Moon, professor of sociology at Vassar, served as thesis advisers for Asian studies major Lesley Richardson ’02, who chose to write about South Korean and Japanese comfort women.

“It touched me that a young American student cared about this,” Qiu says.

While doing background reading on Richardson’s hot-button topic, Qiu found that while there had been a large number of English publications on the experiences of Korean and Japanese comfort women, “there was a serious lack of English-language publications about Chinese women’s enslavement during the war.”

There had been lawsuits, protests, and controversies since the 1990s as Asian researchers encouraged survivors to speak out and demand compensation as victims of war crimes. But their stories had remained in the shadows for decades until 1991, when South Korean survivor Kim Hak-sun testified about her experiences as a comfort woman. Others stepped forward, and Japanese and Korean researchers began to record oral histories and publish documentation. Nationwide investigations on Japanese military comfort stations had started in China, but interviews with Chinese survivors had not been translated into English.

Qiu explains: “Because Chinese women comprised one of the largest victim groups and they, as Japan’s enemy nationals, suffered unspeakable brutality, the lack of this information seriously impaired a full understanding of the scope and nature of the comfort women system.”

She hoped historians would soon step forward to fill this void. At the time, she was deeply immersed in her book on Bashō. But a year after its publication, there was still no English-language documentation of the Chinese comfort women’s testimonies.

As the speaker at Fall Convocation this year, Qiu recalled that time: “I wasn’t sure if I could handle this subject, and there were two voices debating in my mind. One said, ‘You are not a historian, so don’t get involved in this controversial topic. You have a promising study of the Daoist text in hand.’ The other said, ‘These women’s suffering cannot and should not be forgotten. You had the opportunity to learn Japanese and English, so you have the language skills required to help tell their stories.’

Ultimately, I thought back to my days working with Lesley and asked myself, ‘If a young American student could care about human suffering on the other side of the globe at a time long before she was born, how could I, an Asian studies and Chinese and Japanese faculty member who came from the land where the tragedies had happened, see it as irrelevant to my field?’”

She plunged ahead.

The resulting book has a tripartite structure. The first section offers historical background; the third examines the ongoing redress movement and litigation efforts. But the book’s centerpiece presents photographs and first-hand testimonies of 12 survivors. It is one thing to read passages such as “Chinese comfort women, the majority of whom were abducted and detained by Japanese troops in warzones and occupied areas, suffered extremely brutal treatment coupled with a high mortality rate.” It is quite another to hear 79-year-old Yuan Zhulin’s first-hand account of serial rape, translated by Qiu with wrenching directness: “I became so weak by the end of the day that I was unable to sit up. The lower part of my body felt as if it had been sliced by knives.”

The women are now elderly, and as with any trauma victims, there are memory lapses. But it’s hard to discredit the veracity of someone who can provide such details as the braying of donkeys as Japanese troops crossed the river, or being tied up and carted away in a jolting wheelbarrow, or having burning wax dripped on her bare skin. Aware that their research would come under scrutiny by deniers, Qiu and her colleagues took pains to corroborate these accounts with field research.

Su Zhiliang, a male professor of history and dean of the faculty of Humanities and Communication at Shanghai Normal University, set out to collect and document first-hand accounts by the remaining survivors. It was a daunting task. There had been 164 “comfort stations” found in Shanghai alone; more were scattered throughout the vast Chinese continent. But this wasn’t a history anyone wanted preserved. Qiu says the Japanese government has yet to fully acknowledge responsibility for this extensive military-run system—10 lawsuits seeking restitution have all been dismissed, and the so-called Kono Statement, a partial apology issued in 1993, remains controversial, with repeated attempts to rescind it.

The women rarely discussed their ordeals. Because these experiences were so painful to discuss with a stranger, especially a man, Su started bringing his wife, Chen Lifei, a journalism professor, chair of the Department of Publishing and Media, and deputy director of the Center for Women’s Studies at the university. They conducted their interviews in settings familiar to their subjects, funding travel expenses themselves.

The 12 women whose stories are told in the book were selected from over 100 cases documented by the Research Center for Chinese “Comfort Women” that Su and Chen founded. By the time Qiu met the couple in 2006, while doing research in Shanghai, 6 of the 12 women had died. She watched their taped interviews and corroborated their testimonies with the local historical records. Five other survivors from the Shanxi and Hainan provinces had been interviewed multiple times by researchers and legal specialists when they had gone through the legal process to file lawsuits against the Japanese government.

“I wanted to talk to these women directly, but I respected their privacy,” Qiu explains. “These stories are so painful. Each time, it’s like you’re going through that horror again.” Since the five women’s cases had been carefully verified during the legal investigations, Qiu didn’t impose on them for another interview. But in 2008 she did meet an additional survivor, Tan Yuhua, from the Hunan Province, to listen to her testimony.

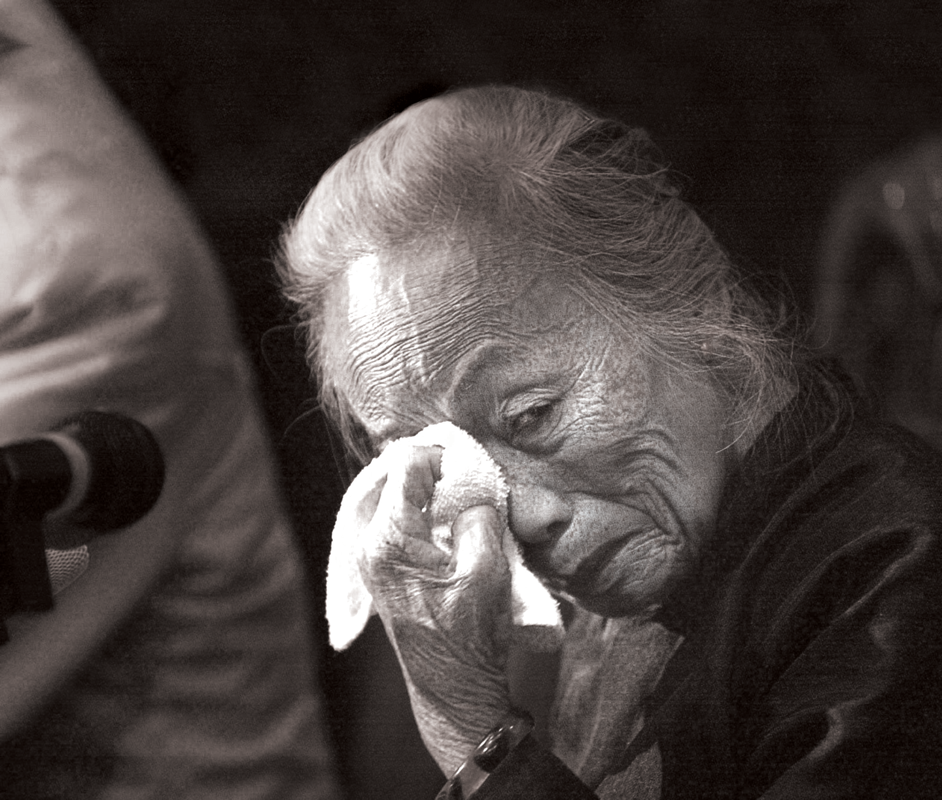

“As I watched the video recordings, it was so painful to see many break down and cry,” Qiu said. She was even more haunted by those who didn’t. She recalled Tan Yuhua’s testimony, which she recalls was delivered without tears, “just a deeply sad, stone-like face”:

"The Japanese soldiers caught my crippled father first. They made him kneel down, and a soldier threatened to kill him with a long, curved sword. I couldn't help crying out, so the Japanese soldiers found and caught me. The soldiers also captured two other girls, Yao Bailian and Yao Cuilian, both of whom were my cousins and schoolmates; both were older than I. One of my aunts died during that attack. The woldiers arrested my father to force him to work for them, but my father was unable to perform hard labor due to his disability, so the Japanese soldiers killed him. I lost my father forever."

Qiu says, “That face is always in my mind.”

There were many challenges over the course of the project. Qiu spent countless hours scouring libraries and archives searching for Japanese and Chinese wartime documents, eyewitness accounts, local histories, and international, legal investigation reports. But time was of the essence. The former comfort women are now in their 80s and 90s, and 10 of the 12 women whose stories appear in the book have died since their interviews were recorded.

Shortly after she started her research, Qiu was diagnosed with Lyme disease. As her health deteriorated, friends tried to steer her away from the arduous project, but she would not be deterred.

"I couldn't stay indifferent, as the survivors' testimonies had really haunted me," she noted in her Convocation address. "These comfort women, whose very bodies were taken as war supplies, were tortured and exploited by the Japanese imperial forces during the war. Then, when the war ended, they were discarded as shamed or traitorous by their own patriarchal societies. Even today, their demands for an official apology and compensation have been denied, and one after another the aged survivors died waiting to see justice done. Their stories must be told."

An eloquent advocate for her book, Qiu did not talk much about her own life. She was born in northeast China, in the provincial capital of Heilongjiang, which translates as “Black Dragon River.” She describes it as “a very cold place, next to North Korea and Russia.” Her father worked in local industry; her mother chaired a provincial women’s federation.

Qiu studied Japanese at Peking University, where she earned an MA in Japanese studies and literature. During that time, she attended a lecture by visiting Columbia professor Donald Keene that provided the impetus for her to look into graduate school in the United States. “I was very impressed by Professor Keene’s lecture, and how Western scholars approach Japanese literature,” she says. “It was a whole new world.”

Eventually, Qiu and her husband both came to study in New York, where she entered Columbia’s PhD program in Japanese literature, learning English as she went along. While writing her dissertation, she taught for two years at Fordham University. Meanwhile, her husband earned a PhD in physics from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and then started working for IBM in Fishkill, not far from Vassar. Qiu began teaching at the college in 1994.

“Twenty years. Oh, that’s fast,” she says.

The paperback edition of Chinese Comfort Women was recently co-published by Oxford University Press and Hong Kong University Press, and the book will soon be published in Chinese by Hong Kong University Press; Qiu is working with her Vassar student assistant on the translation. “So a student/faculty collaboration is at the beginning and the end,” she says with a smile.

“I really hope people in both Japan and China will reach a transnational understanding of the comfort women issue by reading this book, particularly the younger generation,” she adds. “If young people are not properly educated, many people could think nothing like the Holocaust or the comfort stations ever happened. Without knowing this page of history, our memory is not complete.”