From Vassar to the Discovery of the Higgs Particle

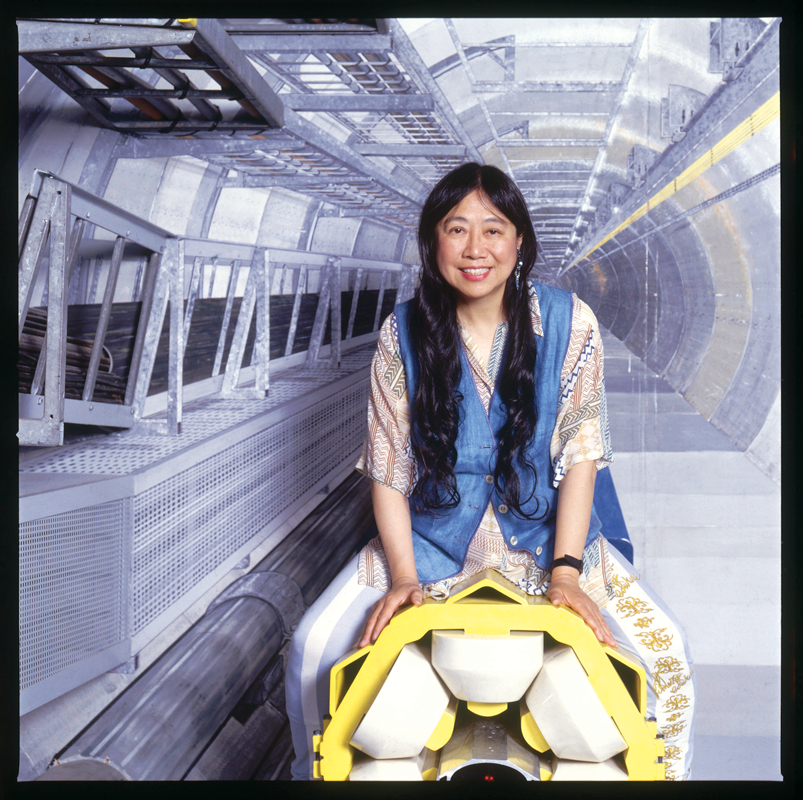

This past May, distinguished physicist Sau Lan Wu '63 delivered more than a commencement address. She delivered an inspiring story about how Vassar helped her rise from on eof the most poverty-ridden sections of Hong Kong to a key position in one of the world's largest and most respected scientific research centers—CERN. Wu played a large role in that organization's recent discovery of the Higgs-Boson particle, said to giver objects mass. The following is an extended version of the speech by Wu, also the Enrico Fermi Distinguished Prfoessor of Physics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

President Hill, Professor Feroe, the Board of Trustees, the eminent faculty, proud parents and grandparents, and Vassar graduates of the class of 2014:

Thank you for giving me this great honor and wonderful opportunity to address today’s 150th Commencement ceremony.

Professor [John] Feroe tells me that I am the first research scientist in 23 years and the first physicist ever to deliver a Vassar Commencement address.

I hope that you will find the story of my journey from Vassar to the discovery of the Higgs particle inspiring and interesting. It is a story of blossoming from a Vassar education, sustained by fierce perseverance.

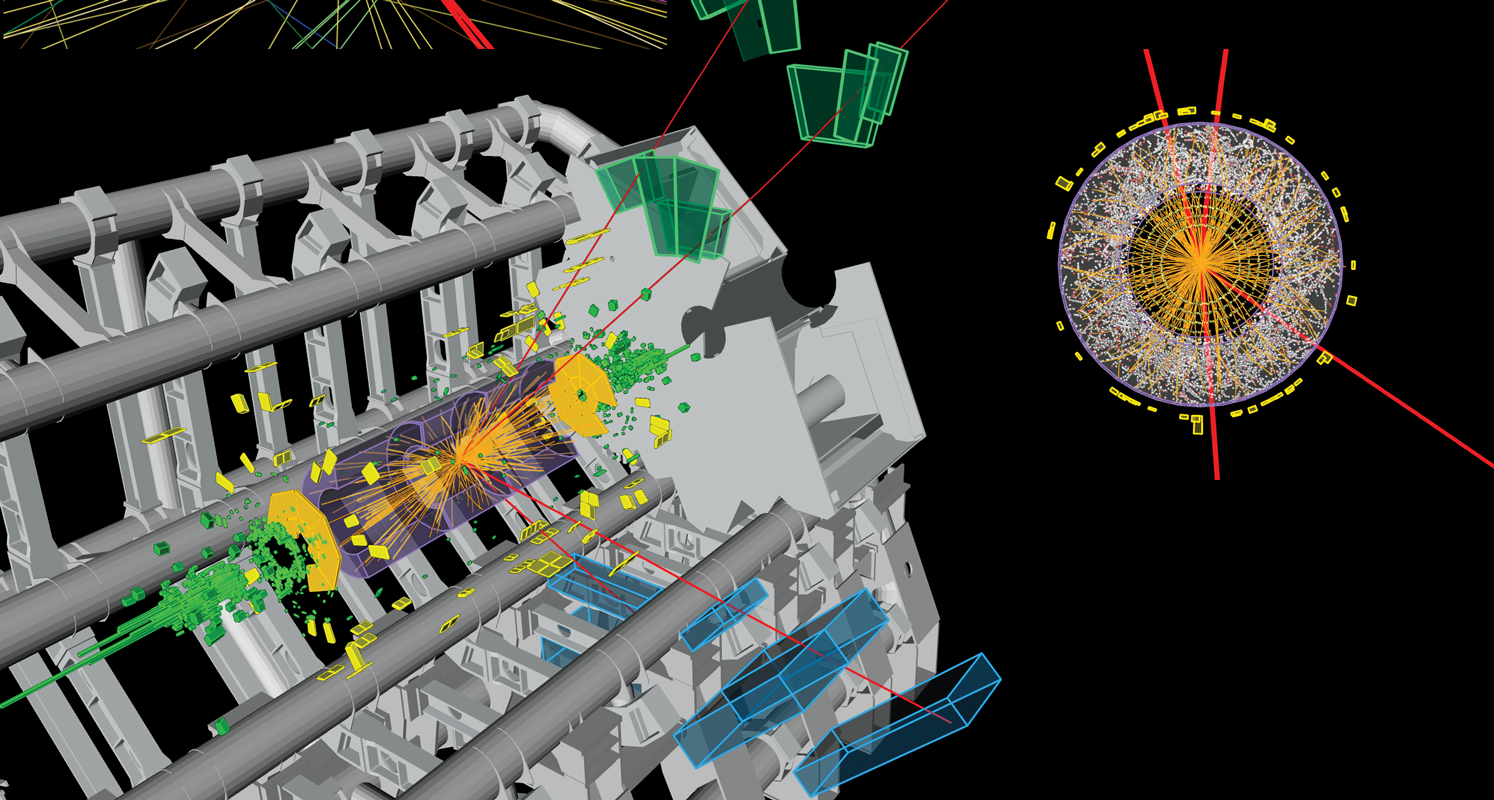

I set myself a goal of contributing to at least three major physics discoveries in my lifetime. So far I have participated in the discoveries of the charm quark, the gluon, and the Higgs particle. I have been telling my graduate students over and over again: in our field of high-energy physics, also called particle physics, taxpayers support our science because our destiny is scientific discovery. My third eminent participation is in the discovery of the Higgs particle. On July 4, 2012, the discovery of the Higgs particle was announced; I am sure you have read about it in the New York Times or CNN. This is a discovery in which my Wisconsin group members and I played a prominent role. This project is so gigantic that two independent teams of 3,000 physicists each, the ATLAS and CMS collaborations, worked at the Large Hadron Collider at the laboratory CERN—the European Organization for Nuclear Research in Geneva, Switzerland. The discovery was a culmination of two decades of hard work by more than 6,000 scientists from 56 nations and about 200 institutions from all over the world.

The most effective way to produce a Higgs particle is by colliding two gluons. Since gluons are in protons, we produce the Higgs particle by colliding two very energetic protons at CERN. To find a Higgs particle, it is like looking for a needle in a haystack the size of a football stadium.

For those who have taken courses in science you may ask, why do electrons, protons, neutrons, and the other particles in our universe have the masses they do? This is a simple question, but profoundly difficult to answer. Discovering the Higgs particle takes us a step closer to answering this question.

Let me briefly explain what the Higgs particle is. It is also called the God particle.

The Higgs particle is a particle needed to explain how elementary particles get their masses. Elementary particles are the building blocks of the universe. The Higgs particle is responsible for all masses, from electrons to humans to galaxies. Without this particle, there would be no atoms, no molecules, no cells, and, of course, no humans.

This particle was proposed in 1964 by three theoretical physicists: François Englert, Robert Brout, and Peter Higgs. Englert and Higgs were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics last year [2013]; Brout, unfortunately, died two years ago.

Let me now share with you the joy of discovery. At midnight June 25, 2012, nine days before the announcement of the Higgs discovery, members in my Wisconsin group, after a number of sleepless nights, obtained clear evidence of the Higgs particle. At 3 p.m. on the same day, on June 25, 2012, there was a commotion in the Wisconsin corridor in the ground floor of Building 32 at CERN. We heard my graduate student, Haichen Wang, saying, “Haoshuang is going to announce the discovery of the Higgs!” Our first reaction was to consider it as a joke, so when we entered my student Haoshuang Ji’s office, we had smiles on our faces. Those smiles suddenly became much bigger as we looked at his computer printout of a Higgs signal plot. Pretty soon, cheers were ringing down the Wisconsin corridor. Haichen Wang was video recording the excitement. We made a large copy of this Higgs signal plot and all my group members signed it. This signed document is now displayed on the wall of the Wisconsin corridor at CERN.

Other groups in the two collaborations observed the same result, with the same excitement. They also have their own stories to tell.

On the day of the announcement of the discovery on July 4, 2012, the auditorium at CERN was locked until 9 a.m. In order to encourage all the students and postdocs of my group to witness the scientific event of the century, I promised a reward of $100 to whoever would line up outside the auditorium overnight. They all got in. At the end of the announcement of the discovery, I went to shake hands with Professor Higgs. I told him, “I have been looking for you for over 20 years.” And I will always cherish his reply: “Now, you have found me.” In fact, it had taken me 32 years, from 1980 to 2012.

On March 5, 2013, my photo with four other physicists appeared on the front page of the New York Times with the heading: “Chasing the Higgs.” This article was written by Dennis Overbye.

Now, I would like to share with you my journey from Vassar to the Higgs discovery.

I was born in Hong Kong during the Japanese occupation. My mother, with me in her arms, ran in and out of bomb shelters. My mother was the sixth concubine of my father, who was a well-known businessman in Hong Kong. However, she was not the favorite of my father’s wives. My mother and I were cast out and we were put to live in a slum. My mother and my younger brother lived in a rented small bedroom and I had a rented bed in a corridor in a rice shop. I grew up with a strong determination to be financially independent of men.

At the end of each school day, we lined up to say goodbye to our teacher with a whip in his hand. I was in a school overcrowded with students. Every time when an officer from the Education Department came for inspection, I had to hide.

Until I was 12 years old, I rarely saw my father.

We then moved to an apartment, and I would see my father once a week for a couple of hours. I impressed my father when he found out that I was able to multiply a three-digit number by another three-digit number in my head. My father believed that the key to success is to be good in English and arithmetic.

My mother grew up on a farm in China, and girls were not allowed to go to school. Hence my mother cannot read and cannot write and has never worked. However, my mother is the most inspiring person in my life. She realized early on in my childhood the tremendous value of education. She did everything in her power to move me and my younger brother from schools in the slum to missionary schools in Hong Kong. I then moved on to a well-known government high school.

When I graduated from high school in 1959, my father did not want me to go to college. “You should now earn your living, and support your mother.” I secretly applied to 50 colleges and universities in the U.S.A., asking for a full scholarship. There were only four colleges that said they would consider me, all women’s colleges—Agnes Scott College in Georgia, Randolph-Macon Woman’s College in Virginia, Connecticut College, and Vassar. I was rejected by the first three. So I was about to be rejected by the whole United States! While in despair, in April 1960, I was overjoyed to receive a telegram informing me that I was accepted by Vassar with a full scholarship. Truly, God decided to send me to Vassar.

I told my father I was accepted by Vassar. He happened to be in New York at the time, staying with a friend whose daughter was about to graduate from Vassar in May, class of 1960. (I would like to find and meet with this alumna of class 1960.) When he attended her Commencement ceremony right here in May 1960, my father realized that Vassar is a very prestigious college. However, he complained that during the reception only peanuts were served. He was proud of my coming to Vassar. With $300, he bought me tickets to go from Hong Kong to San Francisco by ship, the President Wilson line, which took 17 days, and then to New York by train. He gave me $40 for pocket money. He warned me not to go to parties. If I were to lose my scholarship, that would be it!

The day I boarded the ship was the last time I saw my father.

During my trip from Hong Kong to San Francisco, we encountered several typhoons. Few people were in the dining room. I saw my apple rolling from one side of the ship to the other. When the ship disembarked in San Francisco, several Vassar alumnae were waiting for me with home-baked cakes. They were very kind. I then took the train from San Francisco to New York on a five days’ journey with their cakes as my only food. I did not want to spend any money on meals. In New York, Vassar alumnae picked me up and took me straight away to the magnificent Metropolitan Museum. It was wonderful, although I was hungry and tired after the trip and I fell asleep in the museum! I was also taken to visit the beautiful Vassar Club in New York.

At Vassar, I had a full scholarship with room and board, and the American girls donated clothes for foreign students, so I didn’t have to go shopping. Vassar even sent me to a summer school in Richmond, Virginia, the first summer I was here because my English was so poor that I couldn’t pass my requirement. Vassar really made sure I would succeed and graduate. They trained me to have perseverance, persistence, and if you have that, you basically cannot fail.

During my years at Vassar from 1960 to 1963, I felt like a princess staying in an alumna’s luxurious home during school holidays. I distinctly remember Mrs. Washburn, a Vassar alumna who invited me to her beautiful home in an exclusive area of Manhattan. In my first year, I, together with eight other foreign students, were invited to the White House during Easter vacation to meet Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy ’51. I wore a Chinese dress, and my friends were uneasy about the high slits on the sides and kept reminding me to conceal it. We met many wives of congressmen and senators. I was asking myself whether this was intended as an aspiration for our future path.

I buried myself in the library, forever avoiding weekend busloads of Yale men.

My adjustment to the United States was a difficult one. I was unable to see my family for nine long years. I wanted to invite my father to my PhD graduation at Harvard, but he’d died a year earlier. Also, in these early years, some aspects of American culture were unsettling. I visited the Supreme Court of Virginia with two other Chinese girls, and we looked for a restroom. We were confronted with the decision of whether to enter the door marked “White” or “Colored.” We were confronted with that decision again when we got on a segregated bus. That was my first experience with racial discrimination. Of course, the United States has made tremendous progress since that time!

I can never repay Vassar’s generosity, from the dean who allowed me to charge all my books to the college store and to the Vassar girls who gave me clothes to wear. Professor [of physiology] Ruth Conklin created a job for me so I could earn some money. I ironed her suits and burned a big hole in one. I fired myself, and my new job was to move piles of mud from one side of her garden to the other.

Because I never had to worry about my finances on campus, I could focus completely on my studies, hiding myself in the library’s basement for hours on end. I was thrilled with how well Vassar treated me. All of the support—emotional and financial—provided me with great inspiration to be a successful scholar.

I took some art classes, where I made a painting with watercolors and Chinese ink on rice paper. I did not have money to buy a frame, but Professor [of physics] Monica Healea bought a beautiful one and hung the painting in her home.

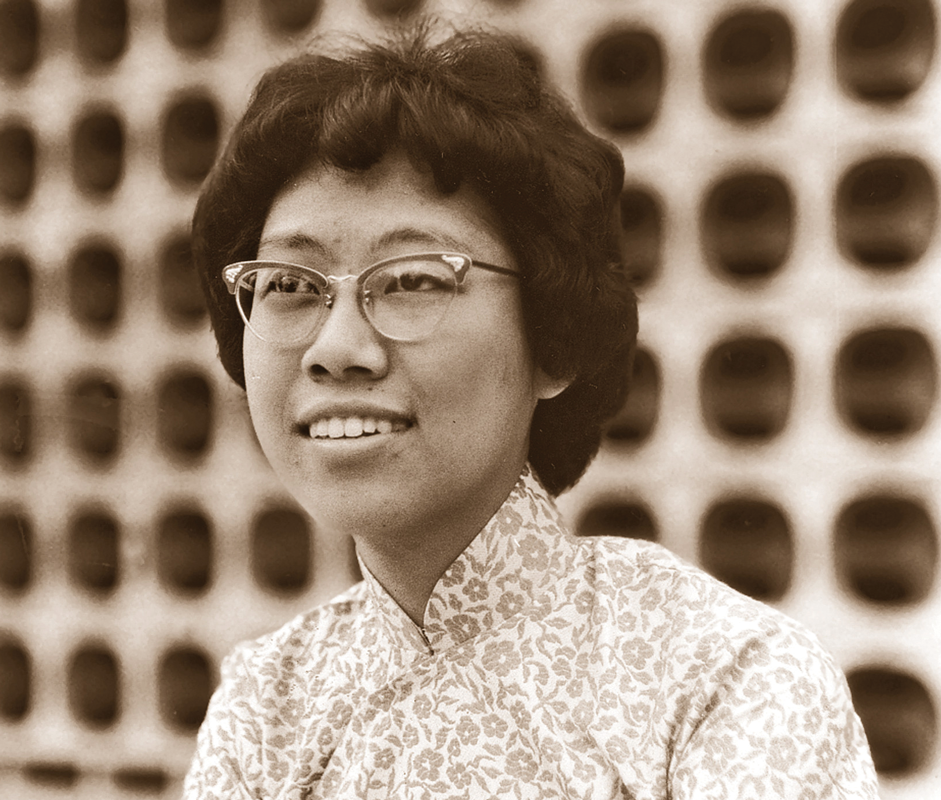

I wanted to be an artist until I read Marie Curie’s biography and decided to devote my life to science. During my stay at Vassar, I worked as a summer student in 1962 and 1963 at Brookhaven National Laboratory on Long Island where I became captivated by the study of particle physics. Those were exciting times, full of discoveries. There I first met my future husband.

After graduating from Vassar in 1963 with summa cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa, I was accepted by Harvard with a fellowship, and also had offers from Berkeley, Columbia, and Yale. Princeton wrote that they only accepted women if they were wives of faculty members. Caltech wrote that they did not have a women’s dormitory and would not accept women unless they were “exceptional!”

My first year at Harvard was extremely difficult: boys did homework together in the men’s dormitories; women were not allowed to go there. I was the only woman in physics in my class. At the end of my first year (1963–1964), I was awarded a master’s degree—it was the first year when women were allowed to get a graduate degree from Harvard. Previously, only Radcliffe College could award such a degree to women.

In May 1964, on graduation day for my master’s degree, I joined some of my classmates for a free lunch offered to new graduates in the Harvard Yard. A guard asked me to leave, and I was kicked out of the Harvard Yard. I was told that no woman had been allowed into this Commencement lunch in 100 years; I left with tears in my eyes.

At Harvard, “We Shall Overcome” [sung] by Joan Baez was my favorite song.

In 1970, with a PhD degree from Harvard, I became a research associate at MIT, participating in the charm quark discovery in 1974 at the Brookhaven National Laboratory. My supervisor, Professor Samuel Ting, was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1976 for this discovery, together with Professor Burton Richter of Stanford.

In 1977, I became an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Another woman physicist and I were the first women professors of physics ever in this university, at that time already over 100 years old.

In 1979, I was the leading figure in the gluon discovery and I was the co-recipient of the 1995 European Physical Society High Energy Particle Physics Prize. The gluon was a new particle that is a carrier of a strong force. It is responsible for binding quarks together to form protons and neutrons. This research was done in the German National Laboratory (DESY) in Hamburg.

The following year, in 1996, I was elected to be a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

As you can imagine, it was not always easy for a woman to be in the scientific field in the ’60s, ’70s, and even ’80s. I remember reading in Life magazine that, if you are a man, people assume you are competent until you prove you are not. If you are a woman, people assume you are not competent until you prove you are. I encountered that mentality a lot early on. If you’re a woman, and there’s something not quite fair and you speak up, people get upset. When I became successful, people would point to me and say that I am an aggressive person. Some have called me the Dragon Lady. I’m not like that, but some people make a picture of you. In the end, you must be immune to this kind of criticism. You have to accept the fact that some people will think that you are less competent. They don’t see that if you are successful, it is because you try very hard and work for it. I have totally devoted myself, my life, to science. Even nowadays, at times, I still experience problems due to racial and gender discrimination.

In late 1970 when I was an assistant professor in the University of Wisconsin, I was at the age when I had to decide whether I should have children or not. My husband and I talked about it and realized that if I did so, I probably would not get tenure, and I would lose all my research funding. Now, today, you would never think about that, but in those days it was a reality. That was the decision I had to make.

I then turned to scientific discoveries and education of young scholars as my primary missions. Over 50 graduate students have received PhD degrees under my supervision. Many moved on to take postdoctoral positions at prestigious places—Harvard, MIT, Princeton, and Stanford, for example. Some of them now occupy very impressive faculty positions in universities. Thirty-three of my former students and postdocs are now professors in the U.S. and worldwide. An additional 11 have permanent positions in research laboratories. Others work in governments or in industries all over the world. I am extremely proud of them and consider them as members of my family. Through them my inspiration has reached out all over the U.S. and in other parts of the world.

How do my graduate students benefit from working with me? My students work with me at CERN in an international environment, and they have a chance to participate in and witness major discoveries in physics. They learn to have the capacity to solve problems under tremendous time pressure, and that is extremely good training for them. The other part of the training they get is competitiveness. They cannot be slow. They are constantly in a friendly competition with young physicists from many other countries. This type of training is especially important in the international, global arena.

Yes, I was warned that it would be hard for an Asian female to have a career in a field dominated by white males, but Vassar and Harvard degrees provided me with the self-confidence and credentials necessary for this challenge. In particular, Vassar College gave me the exclusive opportunity to come to America. Vassar has played a pivotal role in my life and has paved my way to a successful career.

In my career, I am indebted to many. The first one on the list is of course Vassar; a big part of my share of the Higgs discovery belongs to Vassar College.

This address is also dedicated to my 94-year-old mother, Ying Lai; she was not allowed to attend school owing to being a girl in a Chinese village, but she valued education to be of the utmost importance for her children; to my younger brother Ming Lun Yu and his wife, Lynne, whose friendship and dedication to my mother have had an eternal influence on my life; and to my husband, Tai Tsun Wu, who is tremendously supportive of my career.

I would also like to extend my heartfelt thanks to the marvelous support of my research from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the U.S. Department of Energy.

In 1963, I was here by the Sunset Lake, just like you. I was overjoyed. Right here, I made the resolution to devote my life to science and to make a significant contribution to humanity. Since then I have experienced the joy of discoveries, in life as in science. The search may be long or difficult. Often times, it is long and difficult. But when obstacles strike, you fall down and you get back up. We need you in every aspect of our world, from science to society to the arts and everything in between. You believe in yourself. You hold true to your determination. And you will do something great.

Over the past four years, Vassar has armed you with the friendship, and the creativity, and the tenacity to leave this place and achieve great things. Today, you are receiving your degrees. It is your determination that will be most valuable in the journey ahead.

You must believe where others do not. You must act where others cannot. You must lead where others will not. You cannot wait for someone to invite you!

Vassar Class of 2014! Live with integrity and let your conscience be your guide. Be a pioneer and follow your heart, contributing to future humankind. With a Vassar education, and with fierce perseverance and determination, success will be ahead of you and your destiny.

Have faith and luck will follow you.

Thank you again for the profound honor of addressing you, and congratulations, Vassar Class of 2014!

View Vassar’s 2014 Commencement ceremony at vq.vassar.edu.