Writing Their Way Back

More than 45 years have passed since Rob Burden served as an army combat medic in Vietnam, but he still wrestles with what he calls "repetitive thoughts and images" about the war. "The dreams stopped a few years after I came home," Burden says, "but the images are still with me."

Five years ago, Burden began to capture some of these images on paper. “I started writing about my military experiences, but only for myself,” he says. “I didn’t show my writing to anyone.”

Last year, Burden decided to make an exception, sharing some of his haunting memories with fellow veterans in a writers’ workshop called “Voices From War,” run by Kara Frye Krauze ’93.

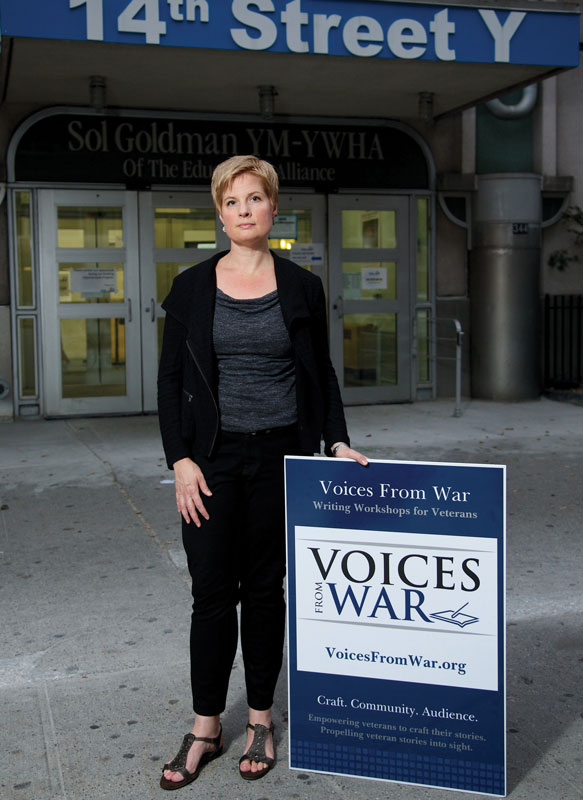

Krauze, whose own stories and memoirs on trauma and loss have been published widely over the past decade, says it’s veterans like Burden that she had in mind when she launched “Voices From War” in 2013 at the 14th Street Y in Lower Manhattan. She said she knew of other writers’ groups for veterans, but none with the same community-focused literary approach. Krauze opened her workshop to veterans of all ages as well as to non-veterans from military families.

"I knew there were already a number of workshops for veterans, but I wanted this to be a space not just for younger vets but for older ones, and their loved ones, too,” she says. Attendees at a recent workshop this fall included two veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan, two who served in Vietnam, several who served during peacetime, and one who was wounded on the final day of the Korean conflict in 1953.

Burden has formed a special bond with Philip Milio, a fellow Vietnam vet who attends the workshops. (Milio’s memoir about being under attack with his army unit was published earlier this year in the military newspaper Stars and Stripes.)

Burden says his decision to break his silence and share his experiences with Milio and others has been therapeutic. “Part of me didn’t want to go to that first class,” admits Burden, who spotted a flier about “Voices From War” on a bulletin board at a VA hospital after an appointment with his psychologist. “But I thought that maybe writing about the things I’d kept hidden all this time, sharing them with a group that would be understanding, might be helpful. And it has been. It’s provided me with a confidence in myself I hadn’t had in the past. Kara sets high standards for our writing, but she’s a very caring person; she has a lot of empathy. I’ve been lifted up.”

Krauze is not a veteran herself, but she credits writing with enabling her to cope with one of the most profound traumas of her life: Her father committed suicide a year after she graduated from Vassar. “That was a seminal event for me, and it shaped what I’m doing now in these workshops,” she says. “It took me a long time to even say the word ‘suicide.’”

Even before her father’s death, while she was majoring in international studies at Vassar, Krauze was interested in how the trauma of war affected soldiers, their families, and others who found themselves near the battlefields.

“My time at Vassar was framed by some pretty huge world events—the fall of the Berlin Wall during my first semester in 1989 and later the war in what was then Yugoslavia, alongside the civil war in Rwanda,” she says. “I didn’t realize at the time the extent to which I would come to involve myself in conflict and trauma studies.”

Krauze continued to explore the issues through her writing while earning a master’s degree in literary cultures at New York University, and she later published selections from a memoir about her father, as well as fiction that explored some of the same issues. She says much of her writing has been cathartic. “Writing about these things became a necessary act; I wanted to create a narrative about things that didn’t make sense to me,” she says.

Krauze uses what she has learned about writing and trauma as she develops the curricula for her workshops. Some participants come with virtually no writing experience, while others have been writing for years, but Krauze says she’s found ways to help those in both categories. She uses war stories—fiction and nonfiction as well as poetry—as jumping-off points for discussion. “I treat it more like a graduate writing seminar,” she says.

Krauze’s formula appears to be working. Several of her students have had their work published, and she’s become acquainted with authors who have earned acclaim for writing about war—such writers as Phil Klay, a marine whose collection of short stories, Redeployment, won the National Book Award in 2014, and Roxana Robinson, whose 2013 novel, Sparta, depicts a marine’s return home after four years in Iraq. Krauze has used both of these works in her workshops and both writers have visited the class, joining in on conversations about writing and war with participants.

One veteran who took Krauze’s workshop, Teresa Fazio, has had a story about a romantic encounter she had with a fellow marine officer in Iraq published on both the New York Times and Words After War websites after winning the latter’s submission contest earlier this year. (Read an excerpt on page 13.) Fazio was commissioned in the Marine Corps through the ROTC program at Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2002. She had written some of her memoir before she joined the “Voices From War” workshop but said she found the atmosphere in Krauze’s classroom at the 14th Street Y to be especially welcoming.

“I was pretty scared to walk into a room full of vets and talk about what happened, but they were totally cool about it,” Fazio says. “Some of what I wrote came directly out of the prompts that Kara gave us. She realizes there are commonalities about the experience ever since warfare began, and looking at these things historically helps bring us all together.”

Another marine veteran, Justin Chotikul, who served in Iraq in 2006 and 2007, says he too enjoys discussing his writing with older veterans and family members. “One reason I love Kara’s workshops is her emphasis on the civilian-military divide,” Chotikul says. He adds, “Unlike a lot of workshops like this, it isn’t confined to post-9/11 vets. It’s freewheeling—you can submit anything you want—but it has a modicum of structure that’s helpful to writers of all abilities and experience. Her prompts really get the creative juices simmering.”

At a recent workshop, Krauze had the participants read a poem about a mother whose husband had served in Afghanistan when their son was very young. As the boy grows older, she struggles for ways to talk to him about war. The poem sparked more than a half hour of discussion, and the consensus was that it had some flaws that needed to be resolved. The conversation then flowed to the value of constantly evaluating and revising one’s work.

Later, members of the class took turns reading passages from the book Several Short Sentences About Writing by former New York Times columnist Verlyn Klinkenborg. Then Krauze concluded the class with a free-writing exercise, asking participants to write a short passage about a stressful event from their past from the point of view of someone else in the narrative.

Krauze’s co-facilitator at the workshop, Nate Bethea, says he is “consistently amazed” by the quantity and the quality of the work that is produced there. A former army officer who served in Afghanistan, Bethea is enrolled in the MFA program at Brooklyn College. “I’m often surprised by our discussions,” he says. “I consider myself a veteran writer, but others in the group often bring up points I hadn’t thought of.”

“Writing about our experiences, either as memoir or as fiction, is restorative,” Bethea says. “A lot of veterans are initially intimidated by the writing process, but workshops like this bridge that gap; they help us get over the hump.”