The History of Anthropology at Vassar College

by Ann Danforth ’11 and Janet Buehl ’12

January 2011

Officially established in 1939, the Vassar College Anthropology Department has developed in a manner that reflects changes in anthropologists’ understanding of culture, history, and power over time. When Vassar was first founded in 1861, the discipline of anthropology was only beginning to make its mark in the world of American academia. At the time, the only anthropology courses offered at Vassar were archaeology courses in the Greek Department, as well as a “General Anthropology” course in the Zoology Department.

From the early 1900s to the mid-1900s, anthropological understandings of people, behavior, and culture were undergoing significant changes. Franz Boas, a German-born American anthropologist, began to challenge early 19th-century social evolutionary theorists and polygenesist “race” theorists who held that cultures follow a universal and unilineal law of cultural evolution and that mental and physical differences among individuals could be explained in terms of race. Boas and his students developed a unique concept of culture that emphasized the equality of all humankind, and celebrated the diversity of cultures. Boas argued that culture is plural, dynamic, historical, relative, and must be studied reflexively (Stocking 1966).

Boas’s insights into anthropological method and theory helped to establish anthropology as a legitimate academic discipline. As part of his challenge to race theory, Boas advocated a four-field approach to anthropology, which included cultural anthropology to show that important human differences are cultural, not biological; archaeology to demonstrate that every culture has a history; biological anthropology to understand human biological evolution; and linguistic anthropology to understand the centrality of language to culture.

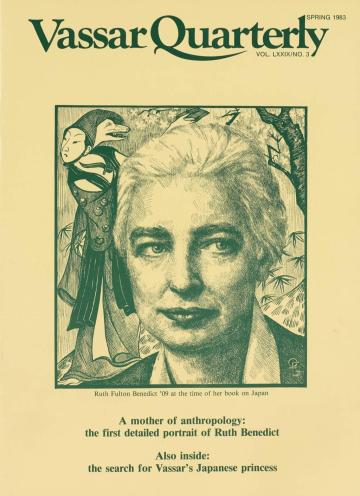

After Franz Boas’ death in the mid-1900s, the Boasian concept of culture was further developed by a number of his students. One such student, Vassar College Class of 1909 graduate Ruth Benedict, pioneered the study of personality and culture. In her book, The Patterns of Culture, Benedict explored the relationship among culture, personality, and the socialization process. She argued that cultures constitute systems with particular patterns, sets of themes, and symbols, which appear in every domain of society. Patterns of Culture also popularized the notion of cultural relativism, which holds that people’s beliefs and actions must be understood within the context of their own culture, and not judged based on the cultural standards of those studying them.

With increased interest in the field, the Vassar College Anthropology Department was established in 1939 with Ruth Mackaye as chair. Four years later, however, Anthropology, Economics, and Sociology were combined as one department. In 1969, Economics became its own department, while Anthropology and Sociology remained combined. During this early period, when anthropology at Vassar was still distinguishing itself from the rest of the social sciences, John Murra joined the faculty at Vassar. Murra, who came from Romania to the United States essentially as a political refugee, was a prominent and respected Andeanist. Between 1950 and 1963, Murra taught a number of courses at Vassar, including “Language Myth and Society,” “The African Heritage,” and a general “Cultural Anthropology” class, which he co-taught with fellow anthropology faculty member Helen Codere. Heather Lechtman ’56 and Nan Rothschild ’59, both students of Murra at Vassar, recall Murra’s tendency to treat students as professionals and encourage their political activism (Barnes: 2009).

The continued importance of Ruth Benedict’s notion of cultural relativism to the discipline of anthropology is reflected in the changes in the Vassar Anthropology Department’s 1978–1979 year curriculum. The Department introduced ANTH-108a, “Comparative World Views,” to expand the vision of majors and non-majors “beyond the confines of American culture.” It aimed to give students insight into their own culture by encouraging them to view it “in the perspective of other conceptual systems.” It also challenged the prejudices and assumptions that made it difficult for students to understand other people, values, and cultures in the way that they understood their own.1

According to early anthropologists like Boas, the best way to gain a real understanding of another culture was to engage in fieldwork, or the collection of data through first-hand observation and interviewing. In the early 1980s, the type of ethnographic fieldwork advocated by Boas became an integral part of the Anthropology curriculum. The Vassar Program in Ethnographic Experience was established as a fieldwork option in 1979, which was “designed to give students the opportunity to carry out ethnographic fieldwork under professional conditions.”2 The growing importance of ethnographic fieldwork within the discipline is further exemplified by the involvement of Vassar Anthropology professors Drs. Walter Fairservis and Lucille Lewis Johnson, their students, and recent Vassar graduates in the 1982 film “Eternal Egypt.” The film, which was produced by the National Geographic Society, explores the history, people, and culture of ancient Egypt through archaeological remains.3

With ethnographic fieldwork established as its hallmark approach, anthropology was finally able to distinguish itself from the rest of the social sciences. In the fall of 1984, the Vassar College Sociology and Anthropology Departments split, illustrating the growth of anthropology as a discipline in the second half of the 20th century.

The relevance of Boas’, Benedict’s, and other early anthropologists’ contributions to the field today is also evident in the way anthropology departments around the country continue to structure their departments and curriculum. The “four field” concept of anthropology advocated by Boas, which stresses the distinctiveness yet complementarity of physical anthropology, linguistic anthropology, archaeological anthropology, and cultural anthropology, served and continues to serve as the model for the Vassar Anthropology Department’s current introductory courses.

Soon after anthropology emerged as a distinct department at Vassar, faculty, students, and alums had the opportunity to gather and reflect upon the development of the discipline as they explored the life and work of Vassar graduate Ruth Benedict. At the 1987 Ruth Benedict Centennial, a number of invited prominent anthropologists and scholars, including Clifford Geertz, James Boon, Richard Handler, and Rhoda Metraux spoke at Vassar about the invaluable contributions of Benedict to the field of anthropology. Many of the speakers were pioneers of a new approach to anthropology called “symbolic anthropology.” Following in the tradition of Benedict, Boas, and his other students, symbolic theorists advocate an approach to anthropology that focuses on the ways people create meaning through interpreting, classifying, and symbolizing. Symbolic anthropologists believe that culture can be found in people’s subjective interpretations of their own events, actions, and beliefs. These interpretive anthropologists continued to emphasize the importance of cultural relativism and ethnographic fieldwork to the discipline of anthropology.

In 1997, ANTH-100: Archaeology, ANTH-120: Human Origins, ANTH-140: Cultural Anthropology, and ANTH-150: Linguistics & Anthropology, replaced ANTH-101a: Representation and Reality and ANTH-102b: Time and Structure to provide for a more “focused” and “appropriate” introduction to the major fields in anthropology.4 At the same time, requirements for a Vassar undergraduate degree in anthropology were also redesigned. Students now need 12 Anthropology units for an undergraduate degree in Anthropology, and are required to take courses in three of the four fields. In addition, two interdepartmental programs, Anthropology-Geography and Anthropology-Sociology, were established.

The continual restructuring of the Vassar College Anthropology Department, its curriculum, and its majors’ requirements since it was first established in 1939 reflects the developments and shifts in the discipline of anthropology as a whole. Understanding culture as plural, dynamic, historical, and relative, and more recently, focusing on the relationship between culture, power, domination, and resistance in an increasingly globalized world, has enabled anthropologists in all of the four distinct fields to appreciate the unique histories, creative experiences, and individual voices of the people and groups they are studying. Despite the many changes in the discipline of anthropology since Vassar’s founding, however, many aspects of the department remain the same. Faculty and students continue to remain dedicated to the discipline, eager to learn more about their own and other cultures, and willing to engage in continual dialogue and debate characteristic of the field.

References

- CCP form, December 6, 1977, Lilo Stern to Dean Elizabeth Daniels.

- Vassar College course catalogue, 1980.

- “News from Vassar,” January 28, 1982.

- CCP form, October 14, 1979, Lucille Lewis Johnson to Dean Norman Fainstein.

Sources

- Barnes, Monica 2009 “John Victor Murra (August 24, 1916–October 16, 2006): An Interpretative Biography.” Andean Past 9: 1-63.

- Stocking Jr., George W. 1966 “Franz Boas and the Culture Concept in Historical Perspective.” American Anthropologist 68(4):867-82.