I didn’t expect to get into Vassar College at all. I only applied with support from the Leadership Enterprise for a Diverse America (LEDA), a nonprofit scholarship program that assists high-achieving low-income students apply to top colleges. Even with their help, I had been on a losing streak: rejected from my top choices, waitlisted from the rest. I refreshed the page and reopened my decision letter, just to make sure. It felt like a miracle, a dream come true. I couldn’t contain my excitement as I bolted out my bedroom door and excitedly told my whole family the news. I was on top of the world for weeks straight, one rose-colored thought permeating my mind: I get to go to Vassar!

As a sophomore in college now, I look back on that memory with slightly less enthusiasm. On one hand, I see it as a major accomplishment on my part, and I still feel a great deal of joy for having brought pride to my family and greater community. At the same time, however, I cannot help but feel embittered by the reality of life at Vassar. In particular, my experience as a low-income student among the children of the elite has left me disillusioned, often questioning why I even decided to attend this school in the first place. I had heard horror stories from upperclassmen in LEDA who went to Yale, MIT, and Stanford, but I never thought the same things they warned us about could happen at the small liberal arts college of my dreams. This was supposed to be my golden ticket to a better life for myself and, God willing, my family. I was supposed to be the one who made it out. Instead, I am left wondering, how much of myself do I have to give up in order to achieve this better life? What did I get myself into?

Maybe this disillusionment is what led me to study religion at Vassar, to find some sort of meaning in my angst. I’ve always been fascinated by religion, perhaps paradoxically: my father brought me up in the right-wing evangelical tradition that preached God’s love for courageous, masculine men and fire and brimstone for gay boys like me. To my father’s chagrin, the threat of eternal damnation didn’t scare me straight. Still, I couldn’t shake the positive memories I had of church before my coming out. The way I saw it, my father’s church got a lot of things wrong, but that didn’t exclude the possibility of the existence of something higher. In fact, to me, it only reaffirmed it. Surely, the all-loving God we learned about in Sunday school was still out there somewhere. I’ve spent the last ten years of my life attempting to reconcile these conflicting images of God, oscillating between periods of feeling closer to Him and feeling further from Him but never disbelieving entirely. 1

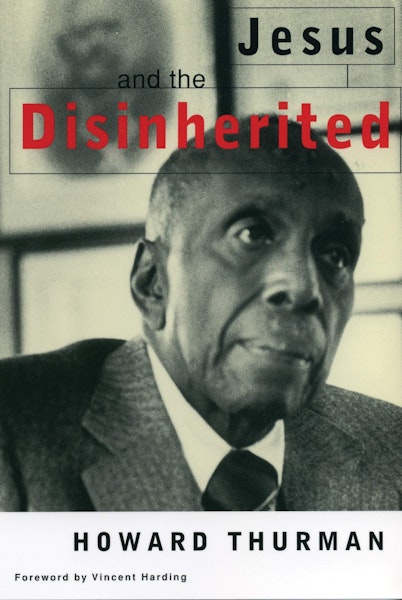

“...one overmastering problem that the socially and politically disinherited always face: Under what terms is survival possible?”

Last spring, I tested the religion department waters at Vassar with one course called “Jews, Christians, and Muslims.” I was hooked. I found it intellectually stimulating and, to my surprise, spiritually satisfying. Finally, I felt that I had a purpose here, which delighted me considering how alone I felt everywhere else on this campus because of my socioeconomic status. I eagerly asked my professor for her recommendations on other classes I could take in the fall. Out of the several she suggested, one caught my eye: “Thurman, Blackness, and Vassar.” I was intrigued. We briefly discussed Black theology in my last class, and I would’ve liked to learn more. The reference to Vassar also piqued my interest—Vassar, as in my Vassar? The same Vassar where I felt myself struggle to form connections with many other students because of our vastly different backgrounds? Curious as ever, I signed up for it. I’m grateful I did, too, because it was in this class that I first encountered the writings of Howard Thurman.

Howard Thurman was a mid-20th century Black theologian and American civil rights leader. As his work spans from the early 1920s to his death in 1981, any attempt to confine Thurman’s vast, complex theology to a single essence presents a challenge. Indeed, as scholars Walter Earl Fluker and Catherine Tumber argue, “in today’s postmodern intellectual climate, Howard Thurman is, if anything, an even more enigmatic figure.” 2 That being said, one identifiable theme that remains consistent throughout his works is the “unity of life and the belief that God is love.” 3 As such, Thurman is often described as a mystic, encouraging an (almost) universalist approach to religion and spirituality with a “deep appreciation of the world’s faith traditions”: “‘What is true in any religion is in the religion because it is true; it is not true because it is in the religion.’” 4 As a Christian minister, however, he did view Jesus Christ as the ultimate source of divine wisdom and comfort. In his seminal 1949 text, Jesus and the Disinherited, Thurman emphasizes Jesus of Nazareth’s position as a poor Jewish man living under Roman occupation, seeking to address “one overmastering problem that the socially and politically disinherited always face: Under what terms is survival possible?” 5

This stood out to me. I had never really considered how Jesus may be a symbol for poor and oppressed people all over the world. Of course, I knew on some level that Jesus preached humility over wealth and greed — I am reminded of the verse from Matthew that goes, “it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God” 6 — but I didn’t think about how that might seriously be applied to today’s sociopolitical landscape. The fact that I was reading this in the midst of my own personal crisis regarding my place at Vassar made the text feel even more accessible and real, and wheels started spinning in my mind. Since Jesus was poor, what does that mean for me as a poor person? And since Thurman is writing about the experiences of Jesus and other Jewish people relative to their environment—that is, a place full of not-so-poor Romans—what may this mean for me in my own environment? Would low-income students at Vassar then be considered a disinherited people in some way? I was rediscovering Christ for the first time, and in many ways I was rediscovering myself. Thurman has essentially provided me with a remedy to the bitterness I’ve been harboring since my arrival to Vassar, a remedy that may similarly be useful for many others in my position.

I must admit that at first, I was reluctant to consider the parallels between Thurman’s writings and my own life. Sure, I knew I was poor. I knew that to be poor, especially at a place like Vassar, came with a set of challenges that a majority of my peers never have and likely never will face. I did have difficulty, however, identifying with Thurman’s description of the paralyzing fear characteristic of many disinherited folks, often victims to “a one-sided violence” by their oppressors. 7 As a Black man in mid-20th century America, Thurman often wrote of segregation, lynching, and other forms of racial violence as modern examples to compare to Jesus’s position as a member of the disinherited in ancient times. What, then, could I know about violence? Put simply, I’m a white guy from Kansas. I’ve never been beaten up, especially not by some rich kids, not at Vassar or anywhere else. Sure, poor people as a collective may have it bad, but how could anything we experience be remotely comparable to the physical, visceral, and often racial violence evoked in Jesus and the Disinherited?

At the time, I failed to recognize the many forms that violence can take. Perhaps distance and time made me briefly forget, but as I confront my past now, I am forcefully reminded that violence is not always a combative Goliath challenging a meek David. Poverty is violence. Addiction is violence. Cycles of abuse are violence. Violence is living in a food desert because the city built a DMV where your old grocery store used to be. Violence is your mother having to raise three kids on a grocery clerk salary for the first ten years of your life because she had no other options without a college degree. Violence is your father donating blood after working hard all day doing construction just to make ends meet. Violence is having to drive him home from the bar on a Friday night when you’re 14 years old because he has a drinking problem that you can do nothing but pray to God about because he can’t afford rehab, especially not without health insurance. Violence is then having to call your mom to take you to the emergency room the following night because Dad, whose mental issues are untreatable without medication that only insurance could pay for, punched clean through a window in a fit of drunken rage and needs stitches in his hand. Violence, as it turns out, was all around me. And still, violence is the hesitation I have to define any of this as violence in the first place. Because every insecure pause I take before speaking my truth is just another moment where Goliath, whoever and wherever he is, can claim ignorance and continue to carry out similar cycles of violence against many other people like me and my family.

...fancy cathedrals, high quality clothes and accessories—all of these serve as physical reminders of who they are and who we aren’t.

Even as our Goliath was nameless and invisible, I was always terrified of the worst to come, some amorphous bad thing that I knew could happen to us because we didn’t have money. According to Thurman, such “fear…becomes a form of life assurance, making possible the continuation of physical existence with a minimum of active violence.” 8 Essentially, while acts of violence are often the initial manifestations of the power imbalance between the ruling class and the disinherited, our fear is what maintains this imbalance in the long run. We do this in the name of self-preservation, paralyzed by the threat of further violence. At the same time, however, it’s as if we’re doing the dirty work for the oppressor: if we remain too afraid to challenge the systems that oppress, those in power have to do little actual labor to keep the oppressive systems alive. Thus, the powerful have found a way to continue to oppress (and benefit from our oppression) from a distance, with minimal effort and engagement with us. This distance is key, particularly in terms of oppression based on class: classism exists because of the social, political, and economic systems that quite literally separate us from the wealthy. Being wealthy is more than the fact of one’s income but an ideology, a state of consciousness that assumes superiority based on the effects and privileges of that income. Such effects and privileges as “artificial limitations….arbitrarily set up, which, in the course of time, tend to become fixed and to seem normal in governing the etiquette of the two groups,” in the words of Thurman. 9 Put simply, rich people don’t live in poor neighborhoods. Remodeled houses, country club memberships, renovated private schools, fancy cathedrals, high quality clothes and accessories—all of these serve as physical reminders of who they are and who we aren’t.

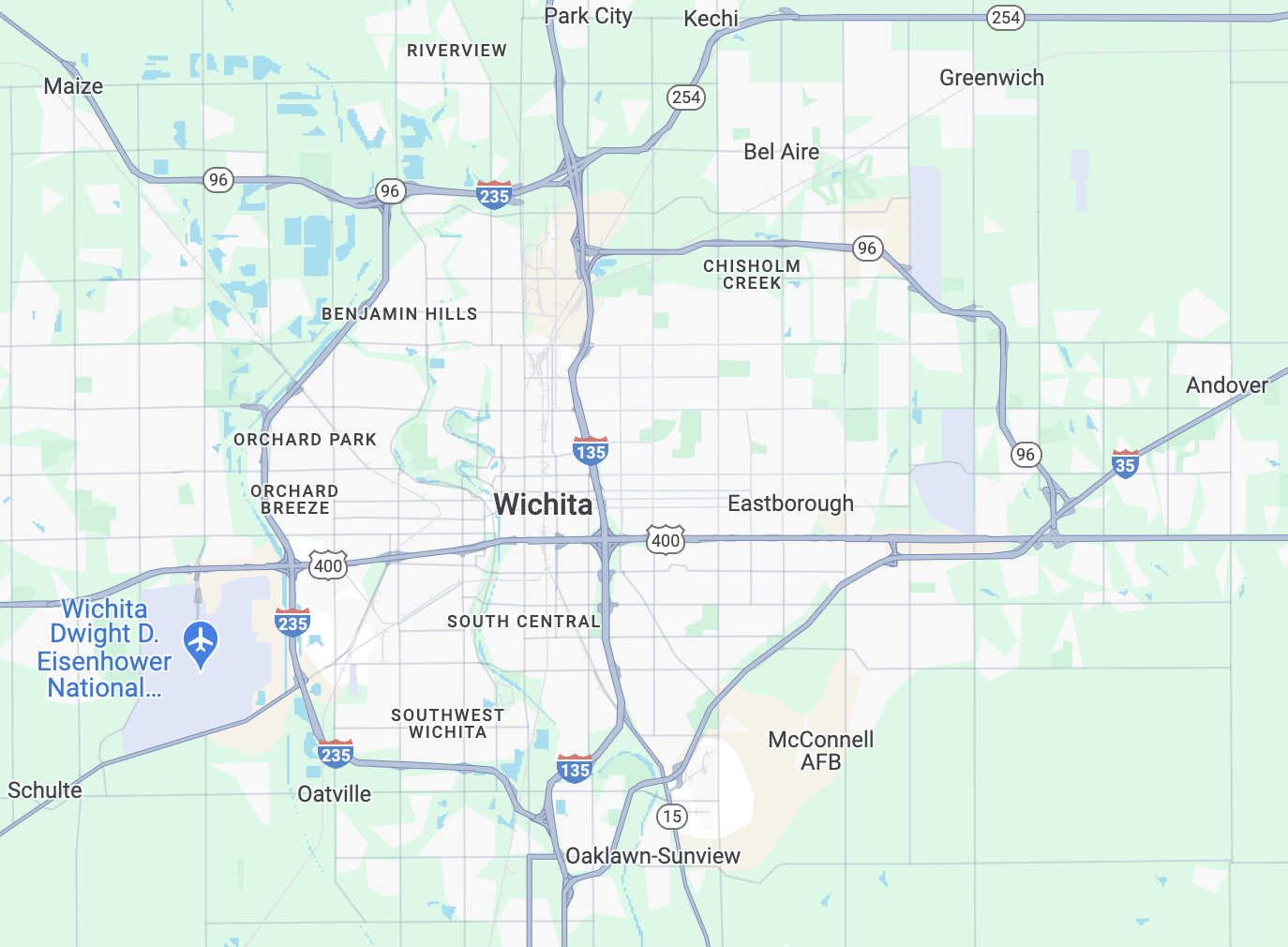

From the time I was three years old until I was 16, I lived in the same community on the west side of my hometown of Wichita, Kansas. My parents divorced when I was six, so my sister and I would spend our weeks at an apartment with our mom and her boyfriend and their daughter, and then on weekends we would visit our dad’s house just a few blocks away. 10 The apartment itself wasn’t too bad. I got my own room, and there was a small playground right behind our unit where we could play and occasionally meet other children from the neighborhood. In sixth grade, however, we had a bedbug infestation that would last for the next five years. We tried to fight them with everything we could think of—home remedies, store-bought products, even the occasional low-cost exterminator—but it was no use.

Our landlord wouldn’t do anything, and we couldn’t afford the kind of treatment that would ensure their complete removal. We learned to live with the bites, to train our bodies to ignore the constant itchiness when we would wake up. As I grew older and tested into an advanced program at a middle school on the other side of town, I began to resent the apartment as a reminder of all that we weren’t. I learned to keep my backpack and clean clothes away from my bed so the bugs wouldn’t be drawn to them and I could at least leave for school without having to worry about my peers finding out about me.

Still, they knew. If not of the bedbugs, at least of where I lived. The majority of my middle and high school classmates were from wealthy suburbs on the east side of town, all having grown up together, so it would have been easy for them to conclude I must not have been. Many of them didn’t care, though; they just ignored me, and I mostly ignored them. I viewed it as a sort of peaceful coexistence, something that didn’t matter in the long run because, after all, we all went to the same school. One day in 10th grade English class, however, I was assigned a pair project with a boy sitting next to me. He was new to the class, so as he introduced himself he stated that he lived in and previously went to school in Andover, the richest suburb town a couple miles east of Wichita. I didn’t think much of it, so I told him where I was from as well. He shifted a bit, and his mouth curled into a smile as he said, “You know what we would say about you guys at my old school?”

“What?” I asked out of genuine curiosity.

“West side, ghetto side!” He could hardly contain himself. This was the funniest thing in the world to him for some reason, but I was too stunned to say anything back. He eventually finished his laughing fit after no more than a minute and attempted to casually move on to the assignment as if nothing happened.

It’s been four years, and I still haven’t quite moved on from that interaction. It was a lightbulb moment for me. Moving forward I began to better understand how my socioeconomic position affected my relationships with my peers. My wealthier classmates didn’t ignore me out of mutual respect or some “peaceful coexistence” as I had previously thought. They simply didn’t perceive me at all. I was nothing to them—either nothing or poor white trash, apparently, as I learned from the boy from Andover. It didn’t matter how much I studied, how friendly I was, or how meticulously I cleaned myself of bedbugs before my thirty-minute bus ride each morning. Their attitude towards me had almost nothing to do with what I’d done and everything to do with who I was and where I came from. As Thurman recounts in Jesus and the Disinherited, “the ability of the strong to shuttle back and forth between the prescribed areas with complete immunity…while the position of the weaker, on the other hand, is quite fixed and frozen.” 11 The prestigious International Baccalaureate program at Wichita East High was one such “prescribed area,” I came to learn, and I simply didn’t belong there. To many of my wealthier peers, I would always belong on “west side, ghetto side.”

Granted, I’m the one going to college in New York while they’re at state schools back home paying ten times what I pay here to go here, so it’s safe to say they were sorely mistaken. 12

Ironically, Vassar has made me look back on that period of my life with a sense of nostalgia and longing in some ways. I thought my years on the east side of Wichita would leave me well-equipped to deal with the high society types I would encounter at a place like Vassar, but I soon realized how wrong I was. Kansas Rich is vastly different from East Coast Rich, I’ve learned. What I once thought of as wealthy back home is apparently just middle class to most people here—or more specifically, it’s upper middle class, a phrase I’ve come to know as one way that “poor” rich people earn sympathy points from other rich people, a means of feigning humility without forfeiting any real privilege. It’s another way of saying, “We’re not rich, we’re just comfortable.” And it’s everywhere here. I see it in the way people dress, the way they speak, the way they eat, the way they carry themselves. Vassar students are highly skilled in reminding you of everything you’re not, everything that your home isn’t. It’s inescapable, and it’s deeply isolating.

...distance functions as a means for the rich to distinguish themselves from the poor.

To give my peers credit, in my experience, a majority of Vassar students are nowhere as outwardly hostile in their classism as the boy from Andover was. I haven’t been called “ghetto” or “white trash” by anyone, nor have I seen any other poor person be so directly attacked for their class. I should note that my experiences on this campus as a poor person are qualified by my identity as a white man, granting me privileges that many of my other low-income students of other races and genders don’t often receive. White supremacy and classism go hand-in-hand, united with all other systems of oppression under the same mission of increasing the material and social capital of the dominant class at the expense of the rest of us. Therefore, just because I don’t experience direct harassment from other students on this campus doesn’t mean it never happens; rather, it simply has not happened to me or other low-income students I am friends with to my knowledge.

Nevertheless, I know better than to take my Vassar colleagues’ lack of outward hostility as a symbol of their acceptance or tolerance for my lower socioeconomic position. That being said, I don’t believe that they necessarily intend harm or malice but rather ignorance of a system they’ve been taught to uphold from birth. As Thurman writes in Jesus and the Disinherited, “every member of the controllers’ group is in a sense a special deputy, authorized by the mores to enforce the pattern.” 13 It relates to the question of distance again, particularly how distance functions as a means for the rich to distinguish themselves from the poor. While those with money can voluntarily pass through whichever areas they want, those without are restricted in our movement. Vassar used to be one such example of this: a restricted area, limited specifically to the daughters (or children, after 1969) of societal elites. The college technically went need-blind in 2007 under then-President Catherine Bond-Hill, a move that would have hopefully put a dent in Vassar’s status as a safe haven for the elite, but the highest reported percentage of undergraduate students on any need-based financial aid was 67% during the 2011–12 academic year. 14 That is, 33% of the entire student body was found to be ineligible for need-based scholarships or grants, meaning they could afford the tuition upwards of $80,000 per year. 15 However, even that hasn’t been sustained, with the most recent reports of students on financial aid being 53% last year—a 15-percent drop over 11 years. 16 Vassar is therefore very much still a safe haven for the children of the elite, albeit perhaps not as extreme of one as before.

According to societal standards as observed by Thurman, then, we low-income students should not be allowed on this campus. Technically—legally, according to both the government and Vassar policy—we are allowed, but this does little to practically change the attitude of a population served by this institution since 1861 and countless other institutions like it for even longer. We are invading the space that was designed for them. To them, we are like the bedbugs of my childhood, leeching off their wealth like parasites, infesting and corrupting wherever we go. This further reaches one major cause for the desire for separation of spheres in the first place: by inventing distinct spaces wherein we can’t enter, they are guaranteed to limit their interactions with us. In doing this, they don’t have to bear witness to the violence they’re complicit in. Rather, they are allowed to live blissfully ignorant. This is why our presence is so dangerous to them, or at least uncomfortable: it threatens the continuation of violence through fear that has been set up. We are living together, often next door to one another—a far cry from high school, where my peers could return to their suburbs at the end of the school day. By being in such close proximity to us constantly, then, those from the elite are forced in some capacity to recognize us, perhaps for the first time in their lives. And I imagine some of them must feel guilty, or at least consider feeling guilty, for the horrors they know their class has committed against the likes of mine. And this is where they begin to retaliate, lash out against the rest of us, remind us of their superior positions, even if indirectly and unintentionally.

While I’ve never been called “white trash,” it remains a term I hear often, even in passing. Many upper-class people here say it so casually, using it to generally describe one kind of sociopolitical other they deem appropriate to ridicule—the poor, uneducated white, usually from a rural part of the South or Midwest, simply too stupid to vote their way out of poverty. The kind of people who live in areas that typically skew politically conservative, thus making them deserving of collective punishment for their sins—unlike the good people of holy New England suburbs, of course, who always vote blue no matter who. I noticed this especially in my freshman year, when I was still convinced that I wanted to pursue some path in political science. I once had a professor in political science who, upon asking each of us where we were from, argued with a girl from Idaho over the political ideology of her county. She dared to assert that her county was relatively left-leaning, but in his professional opinion (despite having never traveled to Idaho) insisted that couldn’t be—after all, it was Idaho!

These staple meals in my house are apparently less common in the homes of many of my peers, who furrow their eyebrows and ask while trying to stifle a laugh, “What is that?”

I experience something similar every time I bring up that I’m from Kansas. Immediately, they have a picture in their mind of a farm where nothing happens, and we’re lucky to have electricity and running water. Never mind the fact that I’m from the largest city in Kansas, a metropolitan area almost twice as large as Dutchess County, where Vassar is located. Never mind the classism I endured from students I thought were rich in middle and high school—again, they would be middle to upper-middle class to most of my peers here. All of Kansas is a monolith when I speak, as its only representative at a school with 2,500 students. I feel similarly isolated when I mention food I miss from home. Since coming to Vassar, to remedy my homesickness, I occasionally take the county bus to Target (or, even better, Walmart!) to buy a few cheap cans of chili or boxes of Hamburger Helper brand tuna mixes. 17 These staple meals in my house are apparently less common in the homes of many of my peers, who furrow their eyebrows and ask while trying to stifle a laugh, “What is that?” Likewise, when I mention that my grandparents from Oklahoma hunt deer for food, I’m met with looks of pure horror—because driving 45 minutes to the nearest grocery store and paying for beef that was raised for industrial slaughter instead of killed in the wild and used for all its meat and bones would be a much more civilized and humane way of life.

Of course, these issues are not purely based on my socioeconomic status but rather mixed with general cultural differences based on geographic origin. I do not have this in common with my fellow low-income students from Queens or New Haven or the Bronx. Conversely, I imagine even a wealthy student from the Midwest would have similar moments, struggling to adapt to the cultural norms of their newfound, fellow rich friends from Boston or Manhattan. There are plenty of other issues that do unite me with other students of the same socioeconomic status, however, something facilitated by the Transitions Program on campus. Transitions is an administrative program founded a little over ten years ago as a resource to help first-generation and/or low-income students with matriculation. Initially, it was just a two- to three-day program before freshman orientation where a limited number of students were invited to campus early to begin their adjustment process sooner. It has since expanded to a full four-year program with student interns, biweekly group meetings for emotional support, and our own study and lounge spaces in Josselyn House. I must admit, I don’t often go to meetings anymore—no time—but still, I feel so strongly about this program in particular. Even thinking now, I can safely say that a strong majority of my friends are in Transitions. It is a place where we can foster our own community and develop our identities as low-income students at this college as a collective rather than individuals suffering alone. Whether at official meetings sanctioned by the program or simply when we hang out in smaller groups as friends, we are finally free to talk about the issues we all face because of our class on this campus.

One issue is the very fact that we aren’t allowed to say the word “poor,” even when describing ourselves. It makes others uncomfortable, as many of us have learned firsthand, like another reminder to this school’s wealthy class of our parasitic nature—in turn making them feel guilty for being rich. If we dare bring up socioeconomics with others, we have to do so in a formal or academic way, saying “low-income” or “underprivileged.” Likewise, the issue of breaks is always one that we have to worry about more than others. Many on this campus can afford to go home frequently, in part because they have the financial means but also because they live close enough to drive or take a short train ride. Even among those who may be unable to go home, they still have the means to travel elsewhere during breaks, take mini-vacations with family friends. For me, however, it costs $500 for round-trip tickets from home to Vassar. Many other Transitions students are in the same position, often only going home at the end of each semester (or even more infrequently). The fact of being here, then, presents economic barriers we have to overcome. As much as it may attempt to be, Vassar is not a bubble, and our financial problems still exist even when we live on this campus.

I hear the way they talk about the custodial staff and dining hall workers, and I can see with my own eyes the way they treat them.

Work-study is one way to help with this. As low-income students, we’re guaranteed a job as part of our financial aid package. We aren’t allowed to earn more than $1,500 per semester, 18 but some money is better than no money, so we work. I particularly enjoy working during spring break—two weeks of full-time pay at $15 per hour, leaving me with an additional $1,000 that doesn’t count to the $1,500 limit. My parents aren’t paying for me to be here, so I need that money, like many other Transitions students. However, among a large portion of those who don’t really need the money, there is the idea that because they don’t need it, nobody else does either. To them, work-study is a “side hustle,” a way to accumulate more and more instead of surviving. They simply aren’t aware of our realities.

Truthfully, I don’t believe they’re aware of the realities of other workers on this campus either. I hear the way they talk about the custodial staff and dining hall workers, and I can see with my own eyes the way they treat them. Thanklessness is a disease on this campus. In discussions within the safety of other Transitions students, I can safely say that may be the single issue that infuriates us the most. For us, it is personal; in service workers, we see our parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles, family friends, siblings. It is similar to how I feel when wealthy students use the term “white trash”: I am reminded of my essential difference from everyone else on this campus because of where I come from and the people I call family. In this case, however, it’s more sinister given the relationship that workers have with the school and the students here. We see them every day, cleaning our messes—and rich kids certainly leave a lot of messes that they don’t clean up because they know that someone else will get it—but too often they are disregarded by students without even a “good morning” or “thank you.”

Thurman identifies hate as a common response among the disinherited as a response to their environment: “Hatred, in the mind and spirit of disinherited, is born out of great bitterness—a bitterness made possible by sustained resentment bottled up until it distills an essence of vitality.” 19 Indeed, I have come to hate many of my peers at this institution. I have my Transitions family, and a select few friends outside of that, but nearly everyone else is assumed rich (and therefore responsible for all the poor behavior I’ve identified thus far) until proven otherwise. According to Thurman, this has the purpose of “giving to the individual in whom this is happening a radical and fundamental basis for self realization.” 20 In other words, just as fear is a tool for self-preservation, hatred is an extension of this, an attempt at repositioning ourselves as the subject in our own lives rather than objects—not a fully realized uprising against those in power, for we still fear the violence that may come, but a controlled rebellion in our hearts. We recognize that we are just as deserving of all that those in power possess, so we delude ourselves that we have agency in our status as disinherited: they don’t just hate us, we hate them just as much, if not more. It does nothing to improve our material conditions, but it eases the symptoms in day-to-day life. We take back our power.

This is the strategy that has kept me going at this school for the past year and a half. Truthfully, it’s a strategy I mastered before I even came here, something ingrained in me in my adolescence that has only gotten more extreme with my changed environment. It does come with its fair share of casualties, however. To invoke Thurman again, “once hatred is released, it cannot be confined to the offenders alone.” 21 In my hatred for quite literally every other person I don’t know, I inadvertently lump in those who perhaps are low-income, just less vocal about it. Further, because my hatred is based solely on identity rather than ideology, then I inevitably hate people who also believe in uplifting low-income students at this school, despite perhaps being middle-class or upper-middle class (that is, they don’t even belong to the exact oppressing class but rather are simply better off than me and my friends). By doing this, I realize I’m playing a losing game: if I believe there are no good people who don’t share my exact class position, and if Vassar has been established as an institution that clearly doesn’t favor those of my class position, then there is no way for me to see any real way to improve the position of low-income students on campus. We are outnumbered, and we inherently have fewer resources than other groups at this school (including money and connections). If all we have is our anger and hate, we cannot get far. The little taste of power we get from it, the smallest feeling of self-righteousness, obscures any real plans we may devise to better our position. We become dependent on our hatred, which is itself predicated on our continual suffering as disinherited people.

I must admit, I am so tired of being angry all the time. It is physically, emotionally, and mentally exhausting. I feel like a shell of myself, as if my very essence is constantly being split between home and Vassar, between then and now. At the same time, however, I don’t want Vassar to change me. I don’t want to assimilate into the culture of the elite promoted by this school, as I’ve seen happen to so many other ones who made it out.

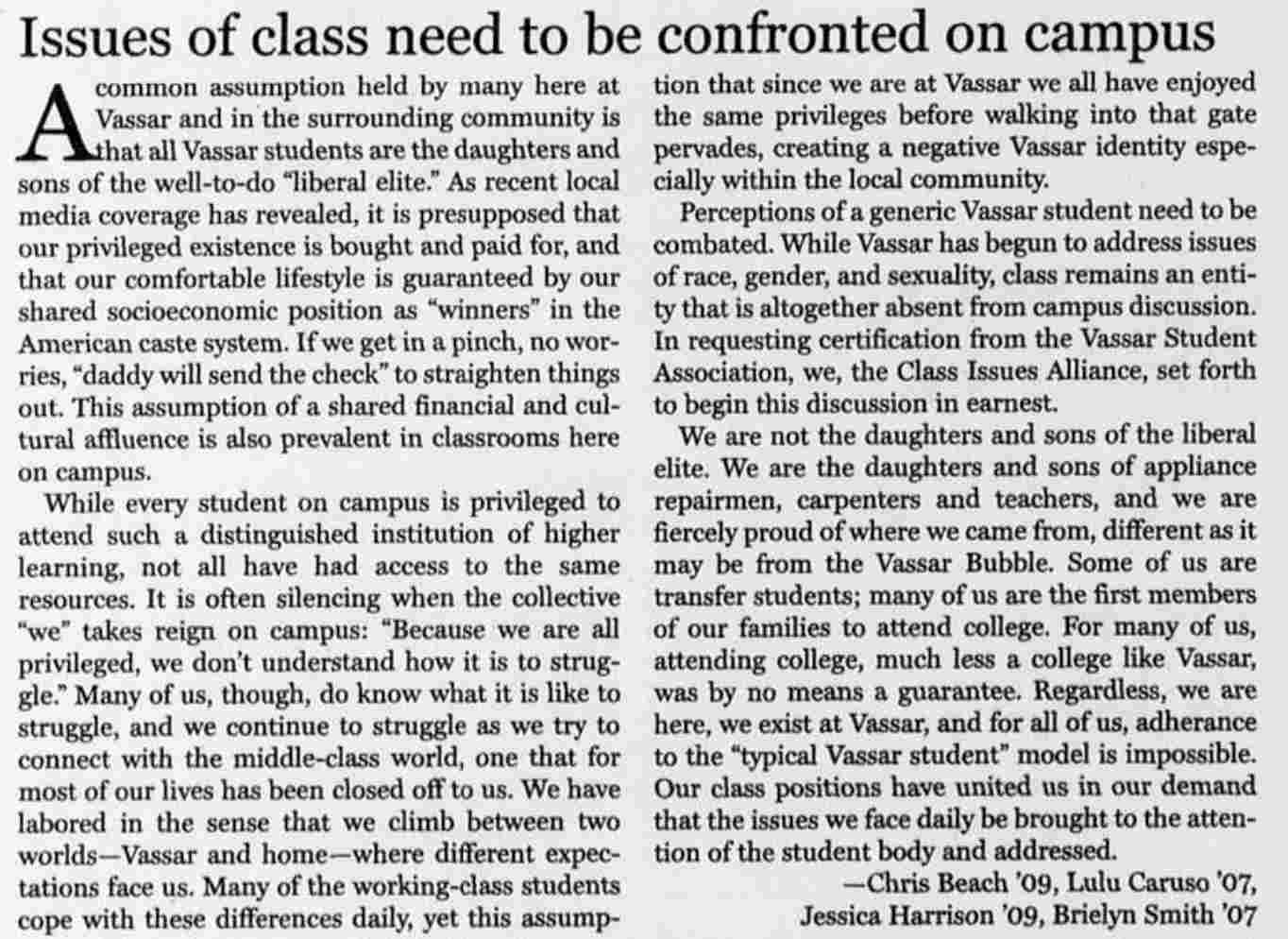

In doing research for my religion class, concurrent with my Thurman readings, I came across old Miscellany News reports detailing the lives of low-income students at Vassar before Transitions. There isn’t too much available—and why would there be?—but it has assured me that my feelings are not unique in the slightest among others like me. One such article in May 2007 was written by four students who dubbed themselves the Class Issues Alliance, a group that (from what I’ve gathered) aimed to bring issues of socioeconomic inequality to the attention of the wider campus community. The final paragraph in particular resonated with me:

We are not the daughters and sons of the liberal elite. We are the daughters and sons of appliance repairmen, carpenters and teachers, and we are fiercely proud of where we came from, different as it may be from the Vassar Bubble. Some of us are transfer students; many of us are the first members of our families to attend college. For many of us, attending college, much less a college like Vassar, was by no means a guarantee. Regardless, we are here, we exist at Vassar, and for all of us, adherence to the “typical Vassar student” model is impossible. 22

Even though the article was published over 15 years ago, I found that it perfectly describes my situation, especially considering my father is a repairman and my mother is a teacher. I cannot relinquish my past to masquerade as a “son of the liberal elite.” I cannot forget who I am and where I come from—both good and bad. In this way, I must hold onto my anger in remembrance of the violence committed against me, my family, and the many others like us. But I must do this out of a desire to create meaningful change, to end and prevent those cycles of violence, rather than allow myself to remain quietly bitter.

Thurman offers one clear solution the disinherited can take to free themselves from the self-imposed trap of hatred: “It is necessary… for the privileged and the underprivileged to work on the common environment for the purpose of providing normal experiences of fellowship.” 23 That is, the only productive way out of the mess I am in, then, is to make a sincere attempt at building community and finding fellowship with those that are different from me. How could I possibly establish a kinship with those against whom I feel diametrically opposed? Thurman again serves as a guide, writing that “love of the enemy means that a fundamental attack must first be made on the enemy status.” 24 In other words, I must radically reconsider every relationship I have with another student on this campus. The very orientation of the “rich student” as an automatic foe must be done away with in my mind, even for those who indeed are rich. After all, the violence in my life was never committed by these people specifically but rather under a system much larger than either them or myself. Who am I to jump to conclusions so quickly and assume they mean harm to me? Further, how often are the roles reversed in some way, even as a result of my response of hatred? How many others may perceive me as an antagonist with no knowledge of the reasons for my anger in the first place?

There is so much uncertainty ahead, both for me and for Vassar as a whole.

Even after acknowledging the flaws in my old way of thinking and setting course on a new path, I cannot claim to know exactly how to love others who have wronged me in the past, those whose elite status benefits from the disinherited position of low-income people. Thurman recommends starting with forgiveness, but even he jokingly recognizes that it can be tricky: “Can the mouse forgive the cat for eating him?” 25 It’s an unsolvable puzzle, a paradox, but the alternative—to remain the hateful shell I was before—is much worse. Therefore, I must find it in myself to forgive and consequently love by whatever means necessary. Thurman reminds us that “God forgives us again and again for what we do intentionally and unintentionally;” 26 Why should I not extend the same grace to others?

In a brief writing from his collection entitled Meditations of the Heart, Thurman comes to the conclusion that “to be in unity with the Spirit is to be in unity with one’s fellows.” 27 The process of forgiving and loving others is therefore not only necessary for the possible end to violence against low-income students as a class, but also for the unification of my own spirit with God. In the broadest sense, this is what I have been ultimately searching for, both in my academic studies as well as in my personal life: to be truly closer to God. And here, after a semester of discovery, Howard Thurman has gifted me with the tools to do just that—and to share this closeness with the Spirit to others through the methods he encourages in his writing.

As I write this, it is ten days away from Christmas, and I’ve enjoyed listening to Christmas music a great deal the past few weeks in preparation for the holiday. I don’t usually think about the songs too much as I listen to them, but one lyric has been on my mind throughout this endeavor: “Peace on earth and mercy mild, God and sinners reconciled.” 28 While obviously referencing the birth of Jesus as the beginning of the point of reconciliation for God and Creation, I find it pertinent to Thurman’s message of unification with the Spirit as well. 29 There is so much uncertainty ahead, both for me and for Vassar as a whole. I’m still unsure of how exactly I will carry out all that I need to in order to achieve this reconciliation for myself, but I have to try to find a way for the sake of myself and those around me. With Thurman’s help, this process of reconciliation has already begun.