Straight from the Source

The Vassar mantra, “Go to the Source” has been part of the College’s culture since Professor of History Lucy Maynard Salmon coined it in the 1890s. Professor of Earth Science Jill Schneiderman took the adage to a new level this spring, traveling with a group of her students to “sources” more than 3,000 miles from the campus. During Spring Break, students enrolled in Earth Science and Science Technology and Society 323, “History of Geological Thought,” visited several venues in the United Kingdom to gain insights into how the science of geology began.

Among the highlights of the field trip, the students stood atop Siccar Point, a promontory on the Scottish coast that is widely acknowledged to be the birthplace of modern geology. It was there in 1778 that Scottish Enlightenment thinker and “gentleman farmer” James Hutton famously concluded that the juxtaposition of two rock formations, the top one horizontal and the underlying one tilted upward, represented time missing from the rock record—in this case, more than 60 million years. Despite being adjacent to one another, the steeply dipping rocks at the bottom of the sequence formed roughly 435 million years ago in an ancient ocean, whereas the horizontal ones were deposited 375 million years ago on land. Termed an “unconformity,” the junction between the rock units gave us “deep time” and pulled thinking about Earth history away from biblical chronologies. As John Playfair, who accompanied Hutton to Siccar Point, wrote:

[There] We felt necessarily carried back to a time when the schistus on which we stood was yet at the bottom of the sea, and when the sandstone before us was only beginning to be deposited, in the shape of sand or mud, from the waters of the supercontinent ocean… The mind seemed to grow giddy by looking so far back into the abyss of time.

At the Geological Society of London, the oldest national geological society in the world, green velvet curtains opened to reveal to Schneiderman and her students the first geological map (1815) to display layers of rock based on the fossils they contained. Having read Simon Winchester’s The Map that Changed the World about William “Strata” Smith and his efforts to map the British Isles, they found themselves transfixed by the beauty and scientific detail of this graphic art printed from engraved copper and colored by hand. And they roamed Lyme Regis on the rocky Dorset coast, where amateur geologist Mary Anning made numerous groundbreaking discoveries by finding and interpreting fossils, including the winged dinosaurs (pterosaurs) that had lived there 66 million to 228 million years ago.

The students prepared for the trip during the first half of the semester by reading about the people and the places they would explore. Together, they wrote a field guide to enhance their understanding of the sites they would visit. But Schneiderman said the course was designed to help her students enhance their learning by literally “going to the source.”

“We didn’t just learn geology,” Schneiderman said. “The trip was quintessentially that of a liberal arts college. We visited James Hutton’s grave, viewed an Andy Goldsworthy sculptural tribute to Hutton at the National Museum of Scotland, and gazed upon the portrait of Hutton at the National Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh—the portrait that appears in every geology textbook that one might encounter. And we learned a bit of women’s history by considering the struggles of Mary Anning, a working-class fossil collector whose finds were frequently attributed to men of the privileged classes of the Geological Society and who faced almost insurmountable difficulties in being accepted by the scientific community.”

Carter Mucha ’23, an Earth Science major from Boston, said the trip had added a new layer to her understanding of science. “This course has shown me that science is a living part of the culture,” Mucha said. “It has demonstrated how important it is to learn about the history of the subjects you’re studying, not just the scientific material itself. It helps you contextualize what you’re learning.

“You look at the outcropping (at Siccar Point), and you realize the work it took for someone to figure out what it meant, and you gain an appreciation for the work and for the discovery,” she continued. “That’s not something you can replicate just by learning in a classroom.”

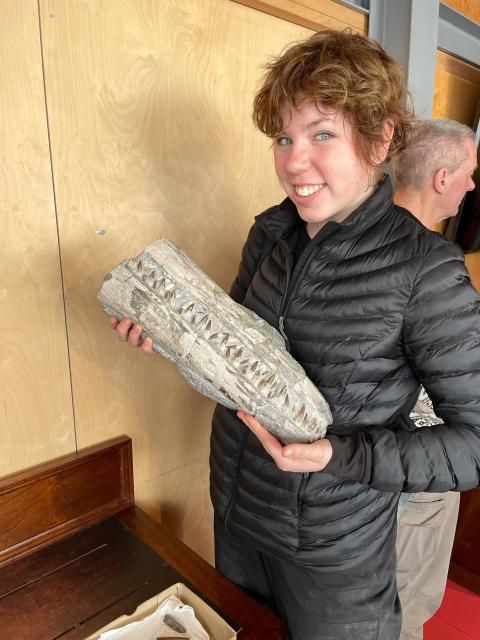

Mucha used her very own first-ever rock hammer gifted to her by her aunt to chisel rocks at Lyme Regis and discover fossils on the coastline where Mary Anning had done the same thing. “It was a wonderful way for us to dip our toes into history,” she said.

Tiara Paul ’22, a Science, Technology, and Society major from the Bronx, said the course had afforded her the opportunity to study science in a new way. “STS is about how society is shaped by science and technology, but this course enabled me to view it from a historical perspective in a way I hadn’t done before,” Paul said.

She said she was especially interested in learning about the challenges Mary Anning had faced being accepted in the scientific community. “She was discredited because she didn’t have the same credentials of many of the men, but she had more knowledge than most of them,” Paul said. “That was illuminating and the kind of thing we talk about in STS all the time.”

Lilly Tipton ’22, an Earth Science major from New Haven, CT, said she had been looking forward to taking the course since she first learned about it from Schneiderman two years ago. “Because of the pandemic, we haven’t been able to gain as much field experience as I would have liked,” Tipton said, “so this course gave me the chance to experience that on a grand scale.”

Tipton said she planned to pursue an advanced degree in geology, “and I’ll definitely take this experience with me, learning not just about the ideas but where the ideas came from.”