The Surprising Legacy of Black Theologian Rev. Howard Thurman at Vassar

Black theologian Howard Thurman has been widely credited with being a mentor to civil rights leaders Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Bayard Rustin, and Pauli Murray. But Reverend Thurman also played a key role in shaping Vassar’s human rights journey, delivering more than a dozen sermons in the Chapel, many of them before the College had knowingly accepted a single Black student.

On February 15, members of the Vassar community convened in the Villard Room—and via Zoom—to witness four Vassar students’ tributes to Reverend Thurman. Croix Horsley ’26, Maya Winter ’26, Jarod Hudson ’26, and Katie Varon ’24 had conducted their research last fall while they were enrolled in a course on Thurman’s Vassar legacy taught by Professor of Religion and Director of Engaged Pluralism Jonathon Kahn.

The event opened with a videotaped message from Billie Davis Gaines ’58, a former President of the Alumnae/i Association of Vassar College (AAVC), who had witnessed one of Reverend Thurman’s talks in the Vassar Chapel when she was a student. She recalled her astonishment at seeing Reverend Thurman, a revered figure among Blacks in the South, at a Vassar Chapel service. And while she said she could not remember what he had said that day, she was awed by his presence. “Today I invite you to consider the continuing legacy of this giant of a figure and leader who tutored his mentee and fellow Morehouse graduate, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in the philosophy of nonviolence, helping Dr. King to fulfill his destiny,” Gaines said. “We might even ask how today’s consideration of Dr. Thurman’s place in Vassar’s history can help the College to fulfill its destiny.”

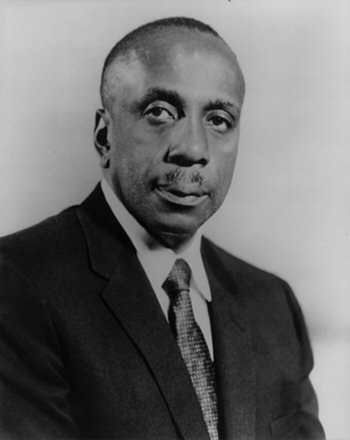

Photo: National Institutes of Health

As he introduced the students, Kahn said their presentations marked the first public event of Vassar’s recently established Inclusive History Initiative, whose purpose is to look more honestly into Vassar’s past. “Looking at Vassar’s history more critically can be difficult and disturbing,” Kahn said, “but Thurman was an activator of activists, and as the semester went on, the students became more energized to tell his story—because we at Vassar must consider not just who we are, but also who we want to be.”

Horsley opened the student presentations by showing a video tribute to Thurman he produced for the course. The film chronicled Thurman’s journey from a humble beginning in racist Daytona Beach, FL, to his accomplishments at Morehouse College, where he graduated as valedictorian, and his time at Rochester Theological Seminary. “[Thurman] became a beacon of peace and love and came to learn and preach the power of nonviolence as a force for change,” Horsley said.

In describing Thurman’s many visits to campus, Horsley noted that his message to Vassar students differed from that of civil rights leader W. E. B. Du Bois, who openly criticized the College for failing to admit more than a few Black students in the 1940s. “Thurman called for nonviolence to lead to a more just society rooted in religious impulse, and that culture reshaped the College, creating a transformative shift to introspection and inclusivity,” Horsley said in the film.

Winter’s presentation, “Uncovering Inequity,” consisted of dozens of articles about Vassar’s civil rights issues she had found in the Black press between 1928 and the late 1960s. Winter noted that these stories appeared not just in New York-based newspapers but also in papers in other parts of the country, such as Pittsburgh and Chicago. Many of these articles were critical of the College, including coverage of Du Bois’s speech, Winter said. Another article noted that while the College had announced in 1935 that it would be accepting applications from Black students, none were admitted until 1940, when Beatrix McCleary broke Vassar’s color barrier. (Actually, another Black student, Alice Turner Howard ’39, had been the first to enroll but transferred; McCleary had been the first to graduate.) Winter noted, however, that when Thurman brought some students from Howard University to Vassar in 1941, the Chicago Defender had reported they had been welcomed warmly. Winter said that while this student exchange had been a positive one, “Vassar was still not doing much to advance social justice.”

In his presentation, titled “What’s the Matter with Vassar?” Hudson spoke of the conflicting emotions he experiences as a student from a low-income family attending an elite institution. Hudson said that while he loves Vassar in many ways, he has also felt hatred for wealthy students on campus.

“So this ‘hate’ strategy worked—until it didn’t,” Hudson said, alluding to what he had learned by reading one of Thurman’s books, Jesus and the Disinherited. In it, Thurman talks about how the Gospel may be read as a guide for resistance for the poor and disenfranchised, and that Jesus is a partner of the oppressed. Thurman concluded that Jesus’s message was that hatred cannot empower anyone and that only through love can justice prevail. “Thurman talked of love and forgiveness and unity,” Hudson said. “Forgiveness is not passivity, but my anger cannot be directed at my fellow students, only at those who perpetuate Vassar as an elite space.”

Varon, the final student speaker, said she had chosen to look at Thurman’s legacy by learning more about his daughter, Olive, who was a member of Vassar’s Class of 1948. Varon said she had found numerous articles in the Miscellany News about Olive’s life at Vassar, many of them written by her. She said that while Vassar’s admissions policy could still be described as tokenism (no more than three Black students were admitted in any year until the 1950s), Olive lived a full life on campus. “We can learn from Olive’s example,” Varon said. “She helped create a food conservation organization and was active in the performing arts and politics.”

Varon said she was struck by one page of the Miscellany News, which carried both a story by Olive in which she praised a Founder’s Day play performed by the faculty and another story about a minstrel show performed by White Vassar students that had won a prize. Olive quickly criticized the College for allowing such a performance. “She praised the College, and she criticized the College,” Varon said, “and those who come after her must be grateful to her for pushing Vassar to a greater future.”

During a question-and-answer session following the presentations, Professor Kahn lauded the students for their work and said he was “struck that the four projects had taken off in such different directions.”

Eric Wilson ’76, Co-Chair of the African American Alumnae/i of Vassar College (AAAVC), concluded the program by adding his gratitude to the students for illuminating this sector of Vassar’s history. “The panelists were awesome,” Wilson said. “Reverend Thurman knew, like my generation of Black college students knew, that you had to be twice as good to compete, and his example will move the College forward.

Gwen Salley ’81, the AAAVC’s other Co-Chair, watched the event via Zoom. Salley said she, too, was impressed by the students’ presentations. “I could not have asked for anything more,” she said. “I sat in awe watching them. Jonathon Kahn was brilliant in challenging them to do this very hard work, and they inspired me to want to read more of Thurman’s writings.”

One special guest at the event, Anton Howard Wong, son of Olive Thurman Wong ’48 and grandson of Reverend Thurman, said he was “blown away” by the presentations. Until he witnessed Varon’s presentation, Wong said, he had not known about many of his mother’s activities and accomplishments at Vassar. “Mom didn’t talk much about all of the things she did at Vassar; she had no ego, just like my grandfather,” he continued. “They never waved their own flags but just set examples for others.”

Kahn said he hoped the event would spark more conversations on campus about the complexity of Vassar’s history. “I knew the students would be incredible, and they were,” he said. “To forge change, you need a map, and I think as much as anyone at Vassar, Howard Thurman provided that map, and the better map we have, the better we can become.”