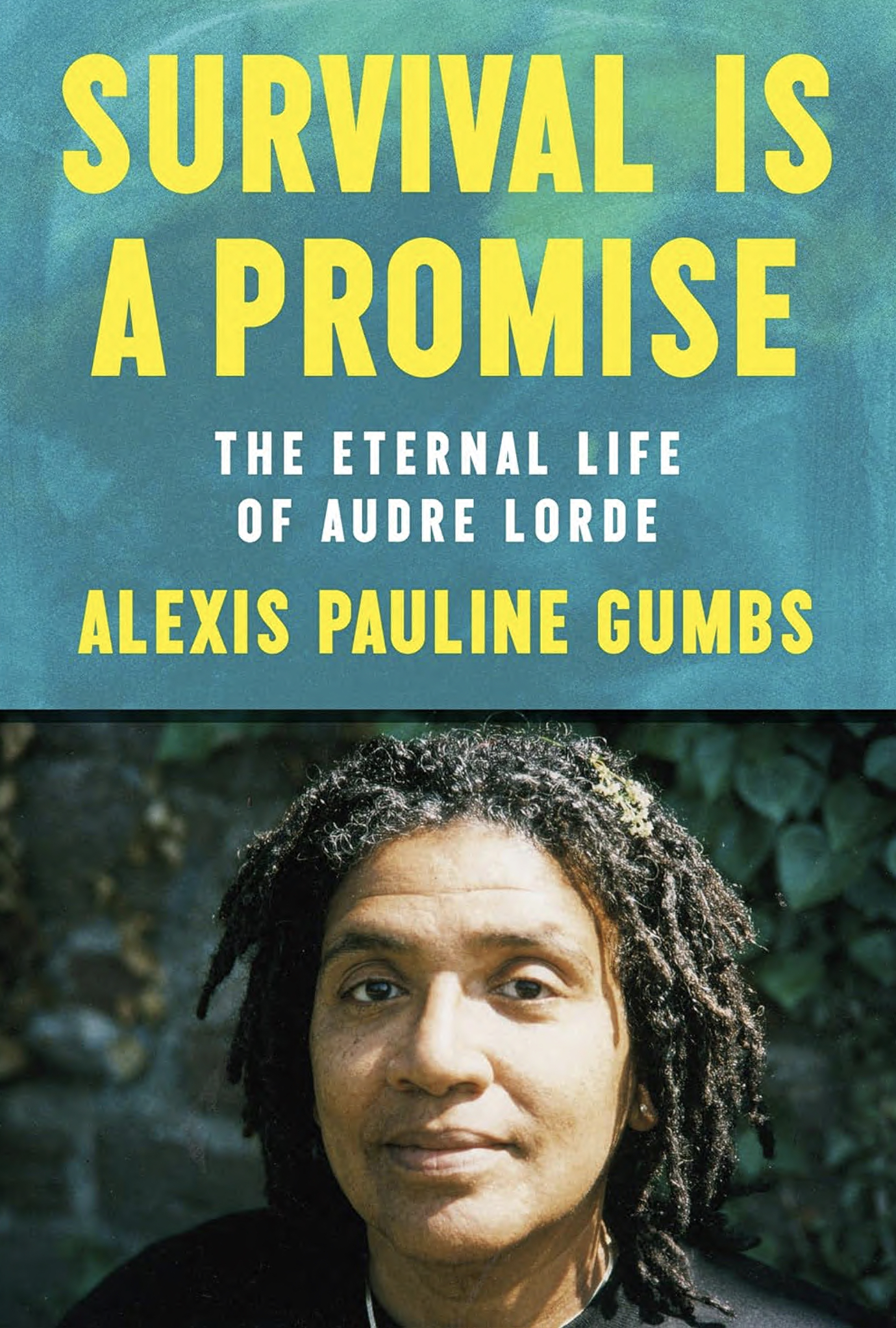

Author Takes a Comprehensive Look into the Life of ‘Warrior Poet’ Audre Lorde

The first line of the bio in Dr. Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s website describes her as a “Black Feminist Love Evangelist and an aspirational cousin to all sentient beings.” That was evident when she visited the campus on February 19 to talk about her book Survival Is a Promise: The Eternal Life of Audre Lorde, published last year.

Photo by Kelly Marsh

One of the first things she did after stepping onstage was to encourage the audience in Taylor Hall to take several deep breaths with her and then to dedicate their time there “to someone who’s not here in this room with us, but who maybe is on our heart, maybe is on our mind.”

Audre Lorde was on her mind, of course. She was a prolific, multi-hyphenate being—an activist, philosopher, essayist, and self-proclaimed “Black lesbian feminist warrior poet,” whose works often explored themes of identity, social justice, and the intersectionality of race, gender, and sexuality. Among Lorde’s most famous works are: The Black Unicorn (1978), regarded as one of her most significant poetry collections. Sister Outsider (1984), a collection of essays and speeches that tackle issues such as race, gender, sexuality, and the need for solidarity among marginalized groups. (This book also includes her most well-known essay, “The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.”) Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982) focuses on her coming-of-age as a Black lesbian, while The Cancer Journals (1980) contains reflections on her experience with breast cancer and the ways in which society marginalizes those who are sick. These works have had a lasting impact on literature and activism, shaping discourse around the topics she touched.

According to Gumbs, writing the most recent biography of the late Audre Lorde felt like it was meant to be.

Gumbs first discovered Lorde’s work as a teen, while participating in a writing workshop at Atlanta’s Charis Books, the oldest feminist bookstore in the Southeast. Since then, she has returned to Lorde’s world over and over again. Gumbs’s thesis at Barnard compared the work of the Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, a feminist press—cofounded in 1980 by Audre Lorde, Barbara Smith, Cherrie Moraga, and Beverly Smith—to the then-contemporary women of color zine movement. Gumbs was the first researcher to explore the full depths of Lorde’s manuscript archives. She had traveled to St. Croix, which Lorde had adopted as her home, to assist Lorde’s partner, Gloria Joseph, with the book Wind is Spirit, to which contributors submitted essays, reflections, stories, poems, and photos that offered slices of Lorde’s life. On the island, Gumbs sifted through box after box of papers, some bearing the stain of flood waters, living in Lorde’s house while doing the research. Over the years, Gumbs had interviewed Alexis De Veaux—who penned Warrior Poet, the first biography of Audre Lorde, almost 20 years prior—several times, once for her dissertation.

One day, when writer and podcast host Sharon Bridgforth was at Gumbs’s home interviewing De Veaux, the conversation turned to why so much time had passed since the first Lorde biography had been published and whether it was time for someone to write another. All eyes turned to Gumbs.

“Never in my mind am I, like, one day I will write a biography,” she noted in an interview the day after the lecture. “I thought that was something other people did.” But it was almost as if Lorde had tapped her on the shoulder, she said—“I had to take responsibility.”

She has since received wide acclaim for the book, which was named a Publisher’s Weekly Top 10 book of 2024, a Time “must-read” book of 2024, and a Guardian book of the week. The biography also was longlisted for the Carnegie Medal in Nonfiction and is a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize.

Gumbs began her talk by reading a passage about the poet’s early life as a rebellious child in a “quiet, tense house.”

Audre’s father had begun having the series of heart attacks and strokes that would soon kill him. Audre’s mother wanted silence in the home so Byron could rest. So it made no sense to Helen why Audre was reciting the same long poem over and over again out loud while she did her ironing, out loud while she cleaned the kitchen, out loud while she haunted the house like a selfish teenage ghost. Their mother asked for one thing, quiet.

But there was no quieting Lorde, and eventually a rupture with her mother would lead her to branch out on her own to an apartment on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Despite a desire to study at Sarah Lawrence, she landed at tuition-free Hunter College. Even then, she had to work several different jobs—including writing pieces for Seventeen magazine—to pay for her housing and food. Gumbs said Lorde had put up with it all to maintain her independence. One passage states:

As young adult, living on her own tenuous terms, Audre needed a new story. Her narrative had to reach beyond her resistance to her mother’s rules in her father’s house. She was on her own now. Her new story had to hold her curiosity and dreams, her wonder about the beginning and end of the species, her suspicions of impending apocalypse, and her deep sense that things could be different.

Gumbs said one of the great surprises in writing and researching for the biography was that Audre Lorde had been obsessed with science fiction. “I had not known that in all my years of loving Audre Lorde, and I was really excited to be able to share that aspect with the world through the book and also with you today.”

Moreover, Gumbs reported, Lorde had been a true “science nerd,” always eager to acquire knowledge about geology, meteorology, biology, the cosmos, marine life, and more. Ecology was also a preoccupation, she said; for Lorde, survival meant more than putting up a good fight against oppression or the cancer that eventually took her life—it was about humans’ ability to survive on an earth in jeopardy.

Gumbs assured the audience that she wasn’t finished with Audre Lorde yet, though she’s not sure all the places her interest in the “warrior poet” will take her.

In addition to the Lorde biography, Gumbs has co-edited Revolutionary Mothering: Love on the Front Lines (PM Press, 2016) and a triptych of her experimental works was published by Duke University Press between 2016 and 2020. Her poetry and fiction have appeared in many creative journals. She has garnered a plethora of honors. Gumbs was a 2020-2021 National Humanities Center Fellow and a 2022 National Endowment of the Arts Creative Writing Fellow. She earned the Lucille Clifton Poetry Prize, the Firefly Ridge Women of Color Award, and a Pushcart Prize nomination. Gumbs was a 2023 Windham-Campbell Prize Winner in Poetry.

Gumbs’s 2020 book, Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals, earned the prestigious 2022 Whiting Award in Nonfiction. The book is a meditation on the evolutionary adaptations made by our aquatic cousins that activists—and humans, in general—might do well to adopt.

Photo by Kelly Marsh

She invoked this theme in a workshop attended by 10 students, faculty members, and administrators the day after her talk. Among other activities, Gumbs asked participants, gathered in a circle, to consider the anatomy of a dorsal fin, which stabilizes movement and allows marine mammals like dolphins and porpoises to set direction. She then asked the participants to consider their own “dorsal practices”—what helps them stabilize and move through the world—meditation, therapy, supportive friends—and discuss it among themselves.

Gumbs’s visit was sponsored by Africana Studies, Dean of the Faculty Office, American Studies, and Women, Feminist, and Queer Studies. Diane Harriford, Director of Africana Studies, said many students had urged the College to bring Gumbs to campus. Three of them—Marissa Desir ’25, Harrison Brisbon-McKinnon ’26, and Shyasia Arnold ’26—introduced Gumbs and offered their own words in poetry and prose, before Gumbs’s talk.

At the end of the visit, Desir reflected, “I first read Gumbs’s work in 2022 and it was unlike any book I had read before. Her work inspired me to acknowledge my listening, learning, and community practices more intentionally … I wished to have others in my community experience her words but also the presence she brings … I appreciate the Africana Studies Department so much for bringing her and taking the time to listen to student voices.”