Program History

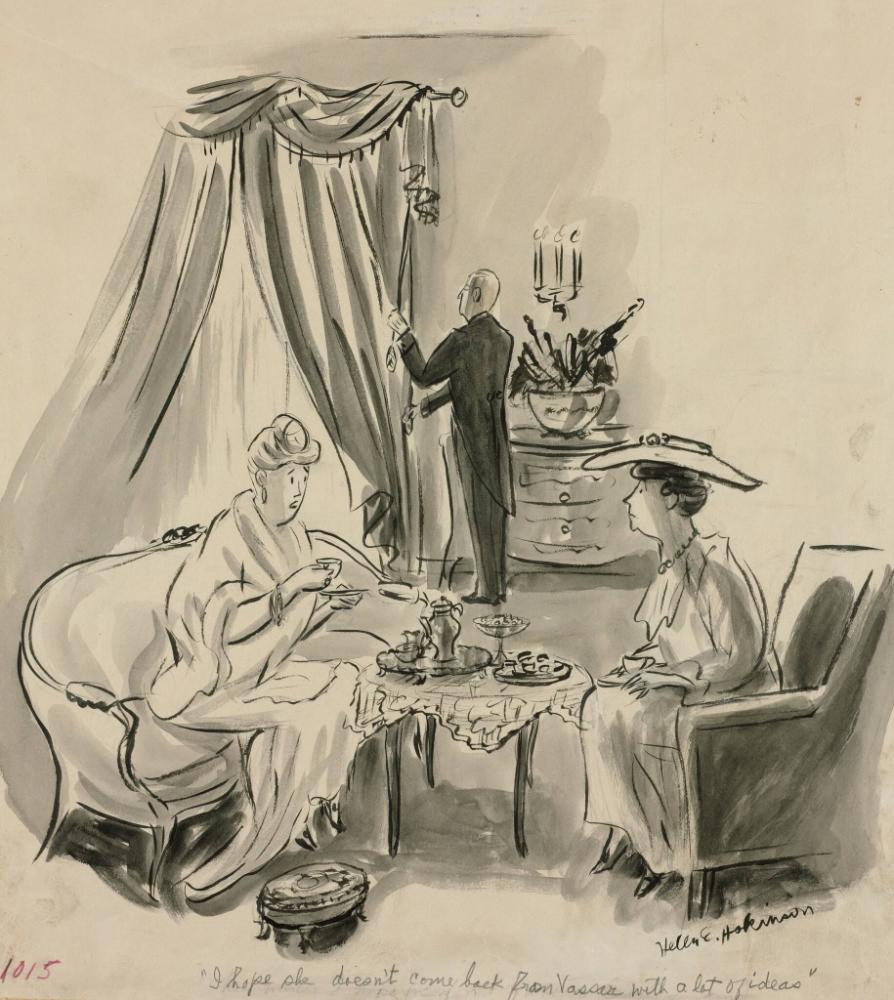

The Women’s Studies Program (recently renamed Women, Feminist, and Queer Studies Program) came into being as a response by students, faculty, and administrators to the Women’s Liberation Movement of the late ’60s and ’70s. The struggle to found the program coincided with and was made more pointed by Vassar’s consideration of a merger with Yale and then with the college’s early experiences of coeducation. Some of the major figures of second wave feminism visited Vassar in these early years, such as Alix Kates Shulman, author of Memoirs of an Ex-Prom Queen (1972), and Joan Kelly, whose 1977 essay, “Did Women Have a Renaissance?” opened up Early Modern Studies to considerations of gender. Foundational feminist work was also produced by Vassar’s faculty, most notably Linda Nochlin’s “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” (1971).

This intellectual ferment complemented the political activism of Vassar’s students, who participated widely in the progressive movements of the late ’60s. Inspired by the black women who had persuaded the administration to found an Africana Studies Program, Vassar’s feminists lobbied for an institutional home for women’s studies. It did not require a takeover of Main, as it had in the case of Africana Studies, for Vassar’s feminists to get the administration’s attention. In general, the students met with a less apprehensive response from the administration, which saw the program as a location for the maintenance of the traditions of the former all-women’s college. Nevertheless, students did not think the institution was responding quickly or forcefully enough to their demands for a Women’s Studies Program, and a November 12, 1976 article in The Miscellany News recorded much discontent on campus. “This place is not committed in any way to human or women’s liberation,” Rob Robertson complained, “but it should be committed to both, especially women’s liberation.” Shana Beamon, a student fellow, informed the Misc that “my freshmen were disappointed in the lack of women’s courses in the curriculum and were surprised there were so few women professors and department heads, especially at Vassar.”

The emergence of a full-fledged Women’s Studies Program took a decade of struggle. At first, Vassar relied on a series of coordinators (Teresa Vilardi, Betty Kronsky and Joan Manheimer) to run an introductory course, which directly addressed contemporary women’s issues as well as the role of women in history, science, and culture. These coordinators were paid for by funds raised from dedicated alumnae by professor of art Christine Havelock. The course began as a series of faculty lectures on a variety of topics and expanded under Manheimer’s direction to include weekly student-led conference sections. “Students should feel that they are as important as the authors being read,” Carol Belkin, one of the conference leaders, told the Misc on February 17, 1978. This challenge to intellectual authority has always been central to the Women, Feminist, and Queer Studies Program.

Christine Havelock took over as the first director of Women’s Studies in the fall of 1978. Havelock’s scholarly and institutional authority as well as her fund-raising skills helped to legitimize the new program. According to a Misc editorial, lamenting the termination of Manheimer’s contract but looking forward to Havelock’s directorship, “it is obvious that without Christine Havelock’s endless devotion to feminism, the achievements in Women Studies would never have materialized” (March 31, 1978). By the 1978–1979 academic year those achievements were substantial: a student at Vassar could major in women’s studies under the auspices of the Independent Program. In addition to the introductory course, prospective women’s studies majors could take an array of courses offered across the curriculum, including offerings with such titles as “Male and Female in Anthropological Perspective,” “Women and History of Political Thought,” “Image and Reality of Medieval Women” and “Women in Victorian Literature.”

Beth Darlington, professor of English, directed the program in the early 1980s. At that moment in feminist studies, the master narratives of history, biology, literature, anthropology, and politics were being challenged and rewritten. Courses that counted towards the women’s studies major were broad investigations of such topics as the family, human sexuality, and images of women in literature and art. As the 1980s progressed, the universal category of Woman, which had been the basis of all these early explorations, came under attack from black feminists, lesbian feminists, and third world women among others. The program responded with new courses and theoretical models that began to address the intersectionality of identity. Moreover, gender construction replaced Woman as the central interpretive category. By the late 1980s, “Construction of Gender,” which would become a staple course of the Women’s Studies Program, had emerged, focusing on “how gender is and has been constructed in culture and how gender distinctions function in forming identity, establishing social roles and hierarchies, and creating structures of symbols and values” (Vassar College Catalogue, 1989–1990).

Since its inception, the Women’s Studies Program benefited from outstanding, dedicated leadership. Following in the footsteps of Christine Havelock and Beth Darlington, Barbara Page, professor of English, took over Women’s Studies in 1985 and skillfully oversaw its transition to a multidisciplinary program. The State of New York officially approved the Women’s Studies Program as a major separate from the Independent Program on September 18, 1985. This new status enabled the program to develop and offer, for the first time, program courses beyond the introductory level. In addition to “Construction of Gender,” the Women’s Studies Seminar, the capstone course for the majors, was initiated in 1987–1988, co-taught by Barbara Page and Jennifer Church, professor of philosophy. In the mid-1980s, Colleen Cohen, Susan Morgan, Karen Robertson, and Mona Harrington staffed two overflowing sections of Introduction to Women’s Studies every semester, while Audrey McKinney anchored Feminist Philosophy. McKinney was the originator of the “no eyeball rolling” rule in classroom dynamics that still guides women’s studies class discussions today.

In the 1990s, under the able directorships of Eileen Leonard, professor of sociology, and Colleen Cohen, professor of anthropology and women’s studies, the curriculum was reshaped to foreground feminism’s global reach as well as the continuing importance of science and technology for feminists. The program also became the curricular location for gay and lesbian studies, which has subsequently transmuted into queer studies. The immense popularity of the introductory course led, in the spring semester of 1990, to an experimental 90-student section, team-taught by three experienced faculty. The student dissatisfaction with this experiment contributed to the takeover of Main Building that occurred in mid-February, 1990. Women’s studies students, who had been encouraged to create connections across differences, were key in building the “Coalition of Concerned Students” that occupied Main Building and demanded an intercultural center, disability access, kosher dining, a rabbi as well as greater focus on the issues racism and sexism across the curriculum. At the height of the crisis, Michael Silverman, currently the executive director of the Transgender Legal Defense and Education Fund, returned to this large, introductory class and declared that he had not expected to come to Vassar in order to join a coalition that was demanding both kosher dining and a gay and lesbian studies major at the same time. The Coalition Dinner, an annual event sponsored by the Women’s Studies Program, continues this tradition of building connections across difference.

In the first decade of the new century, the Women’s Studies Program, led by Diane Harriford, professor of sociology, and Uma Narayan, professor of philosophy, solidified and institutionalized the program’s commitment to exploring race, class, gender, and sexuality as intersecting categories of oppression both in the United States and globally. “Global Feminisms” became one of the options for fulfilling the core 200-level requirements for the program. Questions of race were centrally placed on the introductory syllabus, and a seminar on queer theory began to be taught regularly in the 1999–2000 academic year. These courses were partially in response to the demands of an increasingly diverse student body.

In the decade following Vassar’s move to coeducation, the Vassar student government passed a resolution stating that “whereas Vassar College has a 115-year-old commitment to the special needs of women in education,” it must also “make a convincing demonstration of its commitment to an on-going Women’s Studies Program” (Miscellany News, February 27, 1976). Created out of the activist energy of Vassar’s students and faculty, the Women, Feminist, and Queer Studies Program sees itself as sustaining the original and glorious vision of Matthew Vassar.